Barbara Steele’s Arabesque

“You are a closet, a big closet, with intricate Elizabethan locks made of brass.

“The inside is lined with baize so that nothing can be heard, a place where Mozart rehearsals are held.”

Who talks that way? I never know what to expect from telephone imagist, Barbara Steele. Over the hiss and crackle of our weak connection, she might predict my future or cast some witchy spell — minus any noticeable segue, she once declared, “Flying at night, Danielle, is like being a sperm again.”

Manson on Film

As Charles Manson (Steve Railsback) is being led from the courtroom for the last time at the end of the 1976 miniseries Helter Skelter, prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi (George DiCenzo) tells him, “Everyone’s already forgotten about you, Charlie.”

Well, not exactly, in part thanks to that miniseries. In the 45 years since members of the Manson Family brutally slaughtered seven people on the nights of August 8th and 9th, 1969, Charles Manson has spawned more books, articles, films, TV specials, underground comics and t-shirts than any other criminal in history, with the possible exception of Adolf Hitler. Manson has become a one-man industry, which is pretty amazing for a supposed “mass murderer” never convicted of killing anyone. He’s been mythologized, fetishized, exploited, and commercialized to a point at which Manson himself barely exists anymore, as a number of the films below prove. The public is hungry for anything with the name “Manson” attached to it, and the media is happy to oblige (which is part of the reason Manson is no longer allowed to give TV interviews). From the moment he and members of his family (Tex Watson, Leslie Van Houten, Susan Atkins, etc.) were charged with the Tate/LaBianca murders, Hollywood jumped on the bandwagon. Films with a Mansonian angle (Deathmaster, I Drink your Blood) were rushed into production. Films that were nearly finished at the time of the trial were given a quick rewrite to include a messianic hippie character. Some didn’t go that far, merely changing the poster art, the tagline, or the title to cash in on the Tate/LaBianca killings. And the trial wasn’t even over yet before the first quickie exploitation cheapie based specifically and directly on the case was rushed into theaters. It both does and doesn’t make sense that Hollywood would want to capitalize on the case, given it was their own who were killed, and those who weren’t were paranoid they’d be next. But there you go. Guess the story was just too freaky to leave alone, what with cute hippie chick killers, beautiful and glamorous movie star victims, a desert compound, orgies, drugs, a messiah, a rock’nroll connection, and an apocalyptic scheme.

Nightmare Alley

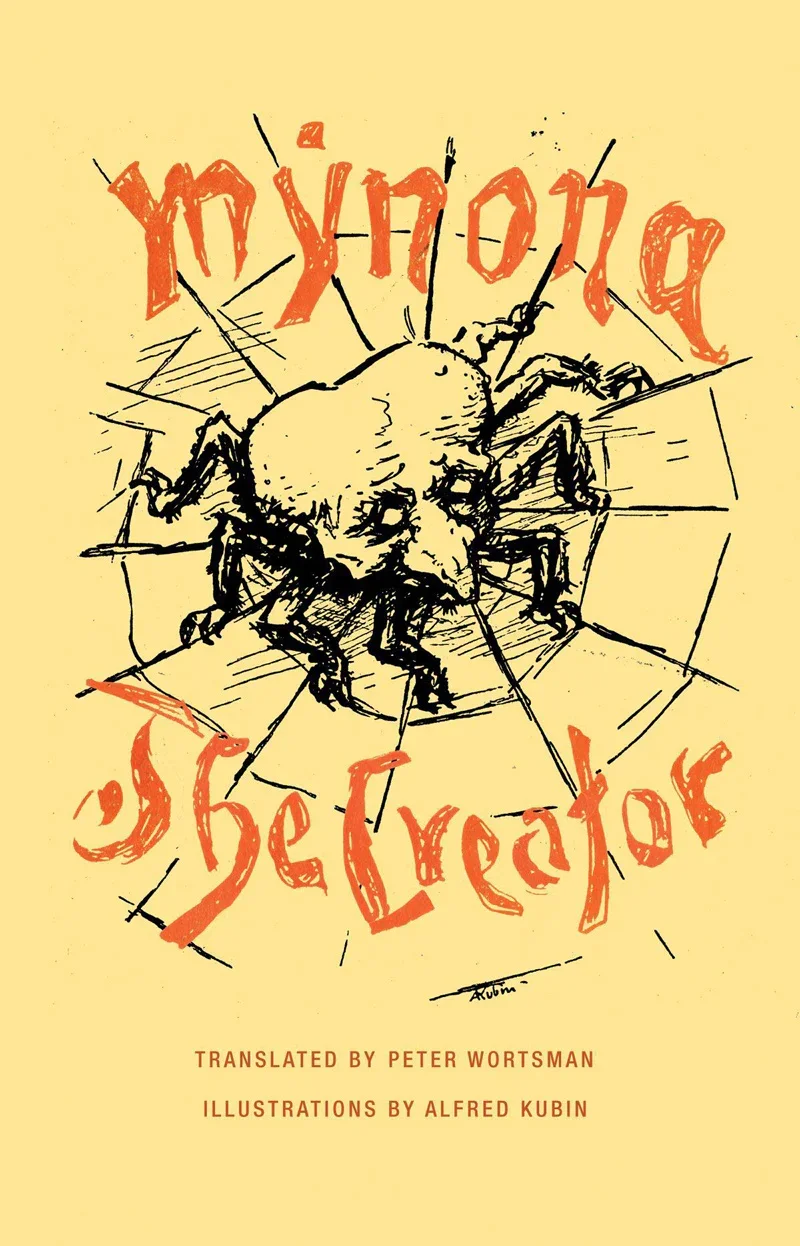

If Mynona hadn’t existed, somebody would have had to invent him. And they did.

For more than 2,000 years leading up to Mynona (AKA Salomo Friedlaender, 1871-1946), since Moses and his tablets broke the bond between God (or the gods) and the world, leaving us only the Word, Western thought was on a collision course with…itself. Immanuel Kant’s philosophy, carefully studied by Mynona, was the ultimate attempt at damage control. He presented an intellectual system that accepted the mind’s divorce from phenomena (nature, to put it less technically) even as it built bridges among other minds via universal a priori concepts. Among them were certain capacities of the imagination. Indeed imagination was the only thing that could rescue objective reality from the status of an illusion. The independent truth of the world couldn’t be proven, but it could be intuited and expressed. By the end of the Eighteenth Century, poets and artists, as ministers of intuition and expression, had glorious and heroic work to do, and they took it on with gusto. For them, exploring the contours of feeling and translating their discoveries into language was like coming to a vast banquet.

Ravachol’s Forbidden Speech (1892)

On trial for murder after a series of bombings, Ravachol attempted to give the following speech, not to deny his guilt, but to accept and explain it. According to contemporary accounts, he was cut off after a few words, and the speech was never delivered. He was guillotined shortly afterwards.

If I speak, it’s not to defend myself for the acts of which I’m accused, for it is society alone which is responsible, since by its organization it sets man in a continual struggle of one against the other. In fact, don’t we today see, in all classes and all positions, people who desire, I won’t say the death, because that doesn’t sound good, but the ill-fortune of their like, if they can gain advantages from this. For example, doesn’t a boss hope to see a competitor die? And don’t all businessmen reciprocally hope to be the only ones to enjoy the advantages that their occupations bring? In order to obtain employment, doesn’t the unemployed worker hope that for some reason or another someone who does have a job will be thrown out of his workplace. Well then, in a society where such events occur, there’s no reason to be surprised about the kind of acts for which I’m blamed, which are nothing but the logical consequence of the struggle for existence that men carry on who are obliged to use every means available in order to live. And since it’s every man for himself, isn’t he who is in need reduced to thinking: “Well, since that’s the way things are, when I’m hungry I have no reason to hesitate about using the means at my disposal, even at the risk of causing victims! Bosses, when they fire workers, do they worry whether or not they’re going to die of hunger? Do those who have a surplus worry if there are those who lack the basic necessities"?

There are some who give assistance, but they are powerless to relieve all those in need and who will either die prematurely because of privations of various kinds, or voluntarily by suicides of all kinds, in order to put an end to a miserable existence and to not have to put up with the rigors of hunger, with countless shames and humiliations, and who are without hope of ever seeing them end. Thus there are the Hayem and Souhain families, who killed their children so as not to see them suffer any longer, and all the women who, in fear of not being able to feed a child, don’t hesitate to destroy in their wombs the fruit of their love.

And all these things happen in the midst of an abundance of all sorts of products. We could understand if these things happened in a country where products are rare, where there is famine. But in France, where abundance reigns, where butcher shops are loaded with meat, bakeries with bread, where clothing and shoes are piled up in stores, where there are unoccupied lodgings! How can anyone accept that everything is for the best in a society when the contrary can be seen so clearly? There are many people who will feel sorry for the victims, but who’ll tell you they can’t do anything about it. Let everyone scrape by as he can! What can he who lacks the necessities when he’s working do when he loses his job? He has only to let himself die of hunger. Then they’ll throw a few pious words on his corpse. This is what I wanted to leave to others. I preferred to make of myself a trafficker in contraband, a counterfeiter, a murderer and assassin. I could have begged, but it’s degrading and cowardly and even punished by your laws, which make poverty a crime. If all those in need, instead of waiting took, wherever and by whatever means, the self-satisfied would understand perhaps a bit more quickly that it’s dangerous to want to consecrate the existing social state, where worry is permanent and life threatened at every moment.

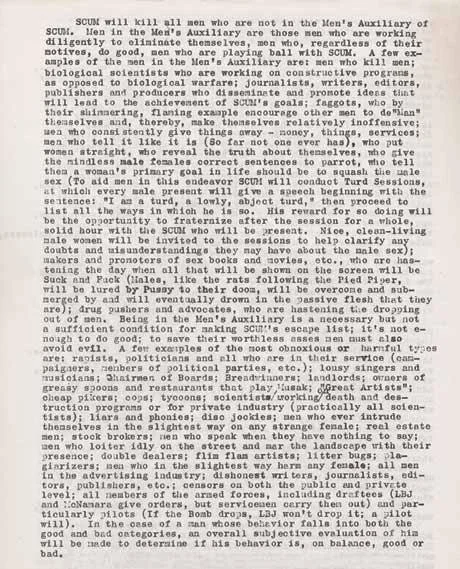

Scum

Valerie Solanas was thirty when she arrived in Greenwich Village in 1966. She’d been a teenage runaway and a drifter for some time, and she was quite damaged by the time she appeared. She grew up in New Jersey, where, according to a sister, their bartender father regularly molested her. Later, when her mother and a despised stepfather couldn’t handle her rebelliousness, they sent her to live with her grandfather who, she said, tried to beat it out of her. She ran away at fifteen and would profess a hatred of men for the rest of her life. Over the next few years she had a married sailor’s child who was taken away from her for adoption, but she still managed to graduate high school and do well at the University of Maryland, earning honors in psychology. After adding a year of grad school at the University of Minnesota she hit the road again, a hobohemian tomboy waif who panhandled and hooked her way to Berkeley.

Boris Karloff Almost Saves the World

Throughout his long and storied career, Boris Karloff played any number of mad scientists whose diabolical experiments (and the inevitable string of murders they required) were aimed at gaining some form of wicked personal glory. He wanted his own unstoppable zombie army, say, or the means to destroy those critics who had laughed at him and called his ideas “insane,” or he just wanted to rule the world.

But around 1940 he starred in a cluster of films in which his mad scientist character wasn’t mad at all, but was only trying to do what he could to benefit all mankind. Unfortunately these sane and noble doctors more often than not found they were working in a mad world, and were destroyed for their efforts. They make for rare instances in which the King of Horror plays a sympathetic role and it is the world around him (and all those stupid meddling fools he’s trying to help) that are the real kings of horror.

Lenny Bruce: Sicknik

In April 1964, Lenny Bruce managed to get himself busted for obscenity twice in one week, and in one location: the Cafe Au Go Go, Howard and Ella Solomon’s new coffeehouse in the basement at 152 Bleecker Street in Greenwich Village. He got the Solomons busted as well. Getting arrested was almost routine for Bruce by 1964. He’d been doing it regularly since 1961. His comedy had made him effectively an enemy of the state.

Born Leonard Alfred Schneider on Long Island in 1925, he was raised by his divorced mom, a dance instructor and performer, and by various relatives. He ran away from home at sixteen and volunteered for the Navy at eighteen, in 1942. After three years of action in the Atlantic he’d had enough war; he dressed up in a female officer’s uniform to get a psychiatric discharge. He got his start in showbiz in 1947, emceeing for his mother and appearing in rigged amateur-hour shows at clubs like George’s Corner in the Village, earning two dollars a night plus carfare. In 1951 he married Honey Harlowe, a redheaded stripper he met in Baltimore. While they were both performing in Miami he came up with a scheme to earn enough cash so that she might quit the business. He created a legal foundation and, dressed as a priest, went door to door in Palm Beach soliciting donations for a leper colony in British Guiana. He later joked that he first considered bronchitis, cholera and the clap before reading an article about lepers. After a week he had raised eight thousand dollars. He was arrested, but since the foundation existed on paper, and he had in fact sent twenty-five hundred dollars to Guiana – pocketing the rest as administration fees – he was found not guilty.

Jean, Shel and Whatever It Was Like Then

It had to have been around 1959, half way through my college life. The Penn humor mag (do such things still exist?) had invited Jean Shepherd and Shel Silverstein to talk. I don’t know why I was part of this, I wasn’t an editor at the mag, though they had an office two doors down from the student newspaper and I was good friends with at least one of the editors.

Shepherd and Silverstein must have come to Philly by train. I remember a few of us driving them to 30th St. Station, I guess to return to NY on the PRR, though the memory feels like we were doing something else.

Who was driving? Anyway, Silverstein (not known yet for his best work, mostly for cartoons in Playboy, etc.) was holding onto the lowered window in the back seat and yelling “Slow down, oh shit,” mildly terrified by our erratically rapid automotive pace along Market St.

Shepherd probably said nothing. Earlier (or later?), sitting on a sofa in someone’s living room, he looked regal and removed and said nothing much then, either. That was his style off-air. He put-up-with.

I don’t recall what Silverstein said or did outside that car ride. Shepherd dominated on stage. In the auditorium of the Museum of Anthropology and Archeology (as it was called with simplicity in those days, no “University of Pennsylvania” prefixed), a perfectly round space with a mesmeric roof of concentric circles of tan brick coffers that, to this day, I can’t say is mildly domed or optically-illusioned to appear so, he made fun of other comics – Mort Sahl and Shelley Berman mostly, though not by name.

He quoted from their minimalist routines – about President Eisenhower and the current administration, he looked out at the audience and uttered (maybe) Berman’s unadorned “Golf Balls! John Foster Dulles!” – which undercut his argument that such comedy was pointless, because the audience laughed even at his once-removed rendition.

On the radio, Shepherd was master of the slow build, the upwelling story of accumulated detail, the apparently directionless personal-history ramble that might take 15 minutes to get anywhere, delivered in an intimate, baritone whisper. He might be your mate at the bar or hanging across a tiny sweat-and-sauce stained table at Crappy Joe’s Late Night Snack Shack. He resented unadorned two-word punch lines that depended on the audience already knowing the comic’s frame of reference. He saw that as laziness, verbal corner-cutting.

Even so, I wondered why Shepherd was dissing other comics – not because comics here and there shouldn’t be dissed, but because he, like they, had broken unstated barriers. Though his barriers (mainly loquacity) were less overt then theirs (political).

Given my addlepated interest in old radio shows, I bought a couple encyclopedias of random radio trivia awhile back. They didn’t mention Shepherd.

How in fucking Christ can you talk about the history of radio and not mention Jean Shepherd? He’s the father of “talk radio” (though he’d be appalled at what it has become). When told by his bosses that he blabbed too much between playing records, he stopped playing records and just talked, into the wee hours of the morning.

Are you a Garrison Keillor fan? I am, sort of, when I think of it. But without Jean Shepherd, there would have been no Garrison Keillor. The shtick, the voice, the outlook, the Keillor assumptions – they’re all Shepherd.

Watching him sitting on the couch, later (earlier?) tooling along Market Street in that open-windowed car, I wasn’t impressed with Shepherd as a person. I got the feeling you could have carved a nicer human being from a bar of soap. Silverstein was a more approachable guy, a voluble OK dude. But Shepherd should be remembered, even canonized. He changed outlooks in a way few of us ever will.

by Derek Davis

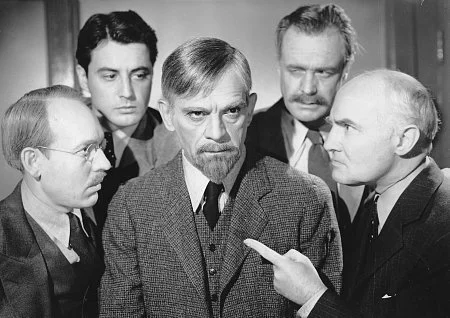

Sympathy for the Devil: “The Hitler Gang”

Nearly seventy years after his death, Adolf Hitler has become a one-man nedia empire bigger than Oprah Winfrey, inspiring countless books, articles, analyses, TV shows, feature films, documentaries, comedies, toys, cartoon references, and songs. One would have to imagine that Hitler wouldn’t find this at all surprising. He might have been surprised, however, to see the first feature drama to take a serious look at his rise to power released while he was still alive.

Directed by John Farrow (Tarzan Escapes, The Big Clock) and released by Paramount in 1944, The Hitler Gang remains one of the most fascinating films made about Hitler for several reasons. Opening at the close of WWI with a blind and bedridden Hitler in an army hospital following a gas attack, the film immediately (via two army doctors) establishes him as a paranoid with a persecution complex. Within five minutes we see where the famous Charlie Chaplin mustache came from, and watch as he becomes a military snitch in order to support a coup to overthrow the new republic. Five minutes in and we already have a clear and unsavory portrait of who Hitler is and how he operates. From that point on the film, at an equally brisk clip, follows Hitler’s rise (with a blend of charisma, deception, blackmail and blunt force) through the ranks of both the ragtag NSDAP and the German political scene at large. Along the way we’re introduced to Hess, Himmler, Goering and Goebbels. We see how Nazi ideology was formed, the Beer Hall Putsch, his stretch in prison, how he finally grabbed supreme power, all the highlights. The pace of the film slows only briefly at the halfway point to take an uncomfortable look at Hitler’s unwholesome sexual obsession with his niece, and how members of his inner circle tricked him into killing her in order to get his mind back on the business at hand.

The first thing that fascinated me about the film given when it was made was how historically accurate it was. Although ultimately it may operate like one, this is by no means a traditional propaganda film, and certainly bears no resemblance to the other anti-Hitler films of the time. There is no exaggeration, no overt editorializing, no myths or outright lies (though some events and back room discussions—as well as the fate of Hitler’s niece—are still the object of some debate among historians). Only at the very end does the stentorian voiceover appear to announce that Hitler is a very bad man who must be destroyed. Prior to that, it’s merely an historical drama and the audience is left to make up its own mind based on the story. No, it’s not a sympathetic portrait — the film makes it perfectly clear that Hitler was an insane, delusional, and dangerous man. But Scarface, Little Ceaser, and Public Enemy weren’t intended to be sympathetic portraits either. Not in so many words, anyway.

That’s the other fascinating thing about Farrow’s film. Any resemblance between The Hitler Gang and the gangster films of a decade earlier is wholly intentional. The title itself tells us that. Hitler is Scarface, an unbalanced nobody with dreams of glory who uses his personal charisma to surround himself with conniving thugs and snatches power by whatever means are handy. (And along the way he also fosters an unhealthy obsession for a younger female relative). Farrow plays this out beautifully, even filming a number of scenes that directly echoed the gangster classics. He must have been very grateful that the historical record played into his hands so well. The only thing the record didn’t offer him was the requisite comeuppance at the end, though he would have had it had he waited a few months. As things stand the film was forced to close with the tide of the war turned in Europe and Allied forces closing in on Berlin, with a Hitler who was (like any proper cinematic gangster) clearly doomed, but still defiant.

Although it was supposed to be another wartime low-budget quickie, Farrow and his crew made it much more than that by putting such care into the detail work, going so far as to hire lookalikes to play the more well-known figures. The real coup was hiring Bobby Watson, an actor who was both blessed and cursed by bearing such an uncanny resemblance to Hitler. It’s a little unnerving to see him here, actually, but he gives a remarkable and believable performance. He had already played Hitler in a handful of comedies but this was his first straight drama in the role, and resists the rug-chewing performance called for in the likes of The Devil With Hitler. After this he would go on to play Hitler in six other films. Likewise The Hitler Gang’s Joseph Goebbels, Martin Kosleck, had previously played Goebbels as early as 1939, and thanks to his cold and severe features, would go on to play Nazis of all kinds over the years.

Although mostly forgotten or simply ignored today as just another bit of Hollywood wartime propaganda, looking at it again, it strikes me that The Hitler Gang might make for a much more effective teaching tool than most straight documentaries when it comes to the question of how, exactly, a phenomenon like Hitler could come about. There is that added risk that certain audience members, as with Scarface, might take things the wrong way, but perhaps that explains the closing voiceover, which fills in for Scarface’s cautionary crawl.

by Jim Knipfel

Charlie Ruggles: Oh My My My

Howard Hawks’s Bringing Up Baby (1938) is a film filled with miraculously perfect comic line readings, and many of them are delivered by Charlie Ruggles as the oft-befuddled Major Horace Applegate, who enters the film over a low (not apple) gate, trying to correct Katharine Hepburn’s Susan Vance as to the time. “Pardon me, the time is 8:10,” he insists, and then he gets stuck astride the gate for a moment. He is wearing a goatee and a Tyrolean hat with a small feather and his light checkered coat clashes dramatically with his dark checkered vest. This is a farce, and so Ruggles’s character even dresses funny, and this is fun but unnecessary, for Ruggles’s stage-trained timing is more than enough to get laughs. When Susan asks who he is, The Major gets confused and dithers, “I’m 8:10,” but quickly corrects himself and announces his own name with a flourish.

Civilization and Its Malcontents: An Introduction

You can go back as far as you like through recorded history, and one thing will make itself obvious. No matter what era, what society you’re talking about on what continent, no matter how wise and just the leadership, no matter how robust the economy, no matter how good-looking the populace, there will always be one person, man or woman, who will take a look around with a slight sneer, put his hands on his hips and say “Y’know, this really sucks.”

Sigmund Freud explained quite neatly why such ornery bastards exist in his 1929 thought experiment, Civilization and Its Discontents.

Civilization, he argues, is by nature both an external and internal control mechanism—an overarching super-ego that lays down rules to restrain fundamental, natural human impulses toward lust, aggression, and greed, and punishments for those who don’t play the game. If you want to take advantage of civilization’s benefits—a ready supply of food and water, police protection, 24-hour Greek diners, and the like—then you must follow the rules. If you don’t, you will be removed from civilization one way or another (imprisonment, exile, execution). Over time (and in theory) the threat of punishment becomes internalized and everyone lives together in peace and harmony as a matter of course.

Constance Collier: A Book Full of Clippings

“Oh, oh, oh, hang the tradition of the theater!” cries Katharine Hepburn as Terry Randall in Stage Door (1937). She’s refusing to go on stage because of a colleague’s suicide, and so her drama coach Miss Luther, played by Constance Collier, has to tell her that the show must go on. Collier herself was an exemplar of the theater, so much so that writer-director Joseph Mankiewicz appropriated her theater debut as a fairy in a production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream as the first theater appearance of his theater diva Margo Channing (Bette Davis) in All About Eve (1950). Collier first found her niche in Hollywood as a vocal coach to silent stars hoping to make a transition into sound, and she was a tough and thorough taskmaster. Colleen Moore reported that when she trained with Collier that they would only work on one word at a time, and theater star Eva Le Gallienne called her “a ruthlessly honest teacher.”