Tinted Wraith

Magic mirrors; celestial mandalas; a sinuous puppet rising like a malign concertina from a well.

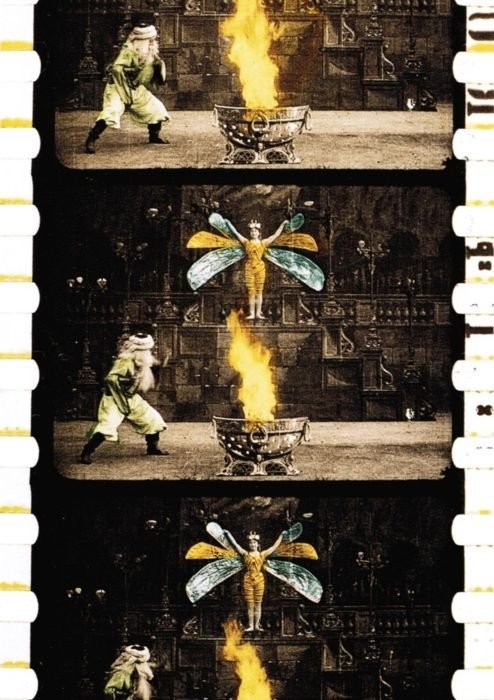

Segundo de Chomόn is such a significant player in film history that it’d be possible to fill an article with his achievements without even describing the films he made at all – special effects artist, photographer, director, he refined color cinematography, combined live action with animation, and built the first camera dolly. The hundreds of films he worked on span the full range of early cinema, from one-shot travelogues in 1903 to Abel Gance’s Napoleon in 1927, for which he devised special effects, he was in the forefront of movie magic his entire life, but the films he’s chiefly remembered for are in the Méliès vein.

Good Night, Mrs. Calabash

According to Durante family lore, backed by childhood photos, Jimmy was an ugly kid, a runt with tiny pig eyes and a huge honker, from the day in 1893 when the midwife swaddled him on the kitchen table in their apartment at 90 Catherine Street on the Lower East Side. Where that house stood is now the site of the Alfred E. Smith Recreation Center. Like his childhood hero Smith, Jimmy Durante never lost his des-dem-youse accent, and never concealed the fact that he only made it through the seventh grade. In fact, he incorporated all that, and of course his giant schnozzola, into his endearing schtick.

His mother Rose had come from Salerno as a mail order bride. His father Bartolomeo, an outgoing eccentric who sported the sort of giant mustache that was stylish in the era, had earned his passage to America in the 1880s by helping to construct the Third Avenue El when he arrived. He then opened a tiny barbershop he ran until he was seventy-five, 86ing any customer who complained about the Caruso and classical records he constantly played on his beloved Victrola. On Saturdays Jimmy’s chore was to lather the gents before his dad shaved them. After he retired Bartolomeo still carried his scissors and clippers in a satchel, offering a free haircut to any guy who looked shaggy to him. Johnny Weissmuller remembered running into Bartolomeo one time and having to fend off the clippers. He explained to the old man that he’d let his hair grow in preparation for starring as Tarzan. Bartolomeo still insisted he looked like a bum. As Jimmy became famous his dad did too. Writing about Jimmy in her column, Hedda Hopper tagged Bartolomeo “Bizarre Bart.” He had it printed on cards, and when Mayor La Guardia declared May 8 1939 Schnozzola Day, Jimmy’s dad rode in the parade with him, handing out the card.

At school Jimmy took daily abuse for his schnozzola. He spent as little time there as possible and dropped out as soon as he could. It was a time when fewer than ten percent of kids in the city completed all eight grades of elementary school. Relatives gave the Durantes a piano, and Bartolomeo paid fifty cents a lesson for Jimmy to learn it, dreaming that his son would someday become a famous concert pianist. He was bitterly disappointed when Jimmy turned to ragtime instead, and for years refused to listen to him play. “Only boozers play that way!” Jimmy later remembered him yelling.

By seventeen he was playing as Ragtime Jimmy in rough saloons full of drunks, gangsters and hookers, like the Chatham on Doyers Street and the hoodlum hangout Maxine’s in Brooklyn, padlocked by the cops in 1915 for being the site of four murders in one week. In Coney Island during the summers he played all night, seven nights a week, at a dive called Diamond Tony’s, at the slightly more upscale Carey Walsh’s, and other joints. Tony was called Diamond because he wore a lot of fake ones. According to Durante, a gunman once held up the joint; when Tony offered to give him his rings, the gunman sneered he could keep them, his wife had better fakes at home. Durante met and became friends with Eddie Cantor at Walsh’s.

He graduated from there to a Harlem nightclub called the Alamo. Al Capone and some of his boys came in one night while he was playing. The boys heckled Durante about his nose, then Capone gave him a ride home and tipped him a hundred dollars, more than his weekly salary. It was at the Alamo that a vaudevillian, Jack Duffy, stuck him with his permanent nickname Schnozzola. He sold a few songs on Tin Pan Alley and worked in more clubs, like the dismally ill-named Pizzazz in Hells’ Kitchen, the midtown Nightingale, and the Paradiso in Italian Harlem, where, biographer Jhan Robbins informs us, “he was a fill-in for the regular pianist who was serving a sixty-day prison sentence for beating up a customer.”

In 1923 he and a couple of partners, the dancers Lou Clayton and Eddie Jackson, performed as a trio, the Three Sawdust Bums, at their own speakeasy on West Fifty-Eighth Street, called Club Durant because the sign painter forgot the e. When he offered to add it for another hundred bucks they said forget it. Later in the decade they opened another club called the Parody. They sang, danced, told jokes, did routines, worked the crowd every way they could. They hired a bad French singer named Fifi just so they could make fun of her. They kidded the stuffed shirts in the audience. Performers in the cabarets and clubs of the 1910s and 1920s had to learn how to step down off the stage and do a floor show, a relatively new concept imported from Paris, pioneering a new, more intimate experience with the audience. Sophie Tucker, shimmying up to the tables and cracking wise with the men, was an expert at it. Durante did it in his own manic way, bouncing all over the room, dancing with the wives, cracking a million awful jokes and then banging out a tune on the “pianer.”

In 1927, when Fanny Brice took ill, the Bums got a shot at biggest-time vaudeville: the Palace in Times Square, the flagship of vaudeville theaters. They were a huge hit, breaking attendance records. Two years later Flo Ziegfeld hired them for the Follies, another step up, and in 1930 they went to Hollywood to appear in their first film, Roadhouse Nights. The trio broke up when Durante signed with MGM (part of the entertainment empire created by another Lower East Sider made good, Marcus Loew).

In the 1934 film Palooka, based on the Joe Palooka comic strip, Jimmy introduced a song he co-wrote with vaudevillian Ben Ryan, the novelty fluff “Inka Dinka Doo.” It was a big hit and his theme song for the rest of his life. Palooka was probably his best picture. Although he would go on to be in more than thirty others, he and Hollywood were never a tight fit. Like other performers who worked their way up from the gin joints and vaudeville, he could be too loud and hyperactive for the screen. As Banjo in The Man Who Came to Dinner he seems to burst in from another movie altogether from the one Bette Davis and Ann Sheridan think they’re making. He caroms around the set, mugs and hams like he’s back in the Club Durant, leaving the rest of the cast looking exhausted. In George Pal’s The Great Rupert he co-stars with a stop-motion squirrel in a kilt, which actually makes more sense than it might sound.

Jimmy did better as a radio and tv personality, unscripted or barely scripted, where he calmed down a little and endeared himself to audiences with his dese-dem-dose and mangled malapropisms. He had a million of the latter. He once told a Metropolitan Opera diva that he loved classical music like “the Midnight Sinatra.” Speaking of “Sweater Girl” Lana Turner, he mused, “Take away her sweater and what have you got?”

It was at the end of his radio show that he started using his famously wistful send-off, “Good night, Mrs. Calabash, wherever you are.” Figuring out who Mrs. Calabash was became a nationwide obsession. He was hounded about it till the day he died in 1980 and never gave up the secret. The most widely accepted theory was that it was a pet name for his wife, who died in 1943, the year he debuted on radio. But biographer Robbins writes in his 1991 Inka Dinka Doo that in fact it was just a gag Durante and a producer cooked up offhandedly, never expecting it to become such a big deal.

by John Strausbaugh

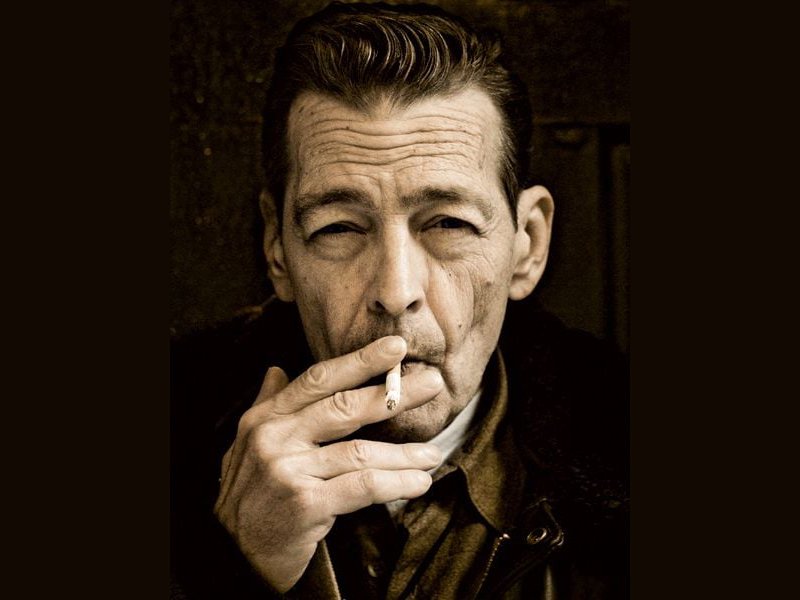

Nick Tosches’ Final Interview

On Sunday, October 20th, 2019, three days before his seventieth birthday, Nick Tosches died in his TriBeCa apartment. As of this writing, no cause of death has been specified. It represents an Immeasurable loss to the world of literature. The below, conducted this past July, was the last full interview Tosches ever gave.

***

In Where Dead Voices Gather, his peripatetic 2001 anti-biography of minstrel singer Emmett Miller, Nick Tosches wrote: “The deeper we seek, the more we descend from knowledge to mystery, which is the only place where true wisdom abides.” It’s an apt summation of Tosches’ own life and work.

Journalist, poet, novelist, biographer and historian Nick Tosches has been called the last of our literary outlaws, thanks in part to his reputation as a hardboiled character with a history of personal excesses. But he’s far more than that—he’s one of those writers other writers wish they could be. He’s seen it all first-hand, moved in some of the most dangerous circles on earth, and is blessed with the genius to put it down with a sharp elegance that’s earned him a seat in the Pantheon.

The Greatest Bad Writer in America: Harry Stephen Keeler

Harry Stephen Keeler (1890-1967) enjoys a peculiar kind of fame as a writer. Or “paper-blackener,” to quote him. The prose of his mystery novels and pulp stories, written from the 1920s into the 1960s, can be simultaneously balled up, discombobulated, lyrical, cryptic – even going “utterly blooey” at times. This is from The Riddle of the Traveling Skull, published in 1934:

For it must be remembered that at the time I knew quite nothing, naturally, concerning Milo Payne, the mysterious Cockney-talking Englishman with the checkered long-beaked Sherlockholmsian cap; nor of the latter’s “Barr-Bag” which was as like my own bag as one Milwaukee wienerwurst is like another; nor of Legga, the Human Spider, with her four legs and her six arms; nor of Ichabod Chang, ex-convict, and son of Dong Chang; nor of the elusive poetess, Abigail Sprigge; nor of the Great Simon, with his 2163 pearl buttons; nor of — in short, I then knew quite nothing about anything or anybody involved in the affair of which I had now become a part, unless perchance it were my Nemesis, Sophie Kratzenschneiderwümpel — or Suing Sophie!

Viewed through the appropriate lens, Keeler’s manifest flaws become avant-garde virtues, as he seems to stretch the novel towards some new form, possibly the radio play or podcast. Neil Gaiman is a fan: “My guiltiest pleasure is Harry Stephen Keeler. He may have been the greatest bad writer America has ever produced. Or perhaps the worst great writer. I do not know. There are few faults you can accuse him of that he is not guilty of. But I love him.”

Among the various devotees keeping this “forgotten author” alive, no one has proven more steadfast than Richard Polt, who chairs the philosophy department at Xavier University in Cincinnati and founded the Harry Stephen Keeler Society. http://site.xavier.edu/polt/keeler/

Richard, give us an introduction to Keeler and his work – and tell us what led you to dedicate so much time and energy to keeping his name alive.

I ran across Keeler by pure accident in 1996, and from the start I was thrilled by the feeling that I was onto something truly weird and forgotten. I’ve always enjoyed digging into some corner of culture, going deep enough that I discover things that just aren’t in sight of today’s conventional wisdom, and finding connections that I would never have found otherwise. That’s exactly what the world of Harry Stephen Keeler has done for me.

Keeler (1890-1967) was a lifelong Chicagoan. His father died when Harry was an infant, and his mother married a series of other ne’er-do-wells who also kept dying on her. Meanwhile, she ran a boarding house for vaudevillians—so Harry was exposed to a wide variety of theatrical types in a city that was teeming with immigrants. He studied to be an electrical engineer and worked for a while at a steel plant, but his real passion was writing. His mom feared that he was going insane, and had him committed to the asylum at Kankakee, Illinois in 1911-1912. But he was released, and managed to make a living publishing quirky little stories with twists. In 1919 he became the editor of the pulp magazine 10 Story Book, which published short fiction and pictures of half-clothed girls. He also edited magazines such as the Chicago Ledger and America’s Humor.

Keeler’s stories began to get more convoluted, and by the late ’20s he was publishing mystery novels with Dutton in the US and Ward Lock in England, including The Spectacles of Mr. Cagliostro, which drew on his experience in the asylum. Things were looking up, but the Depression cut into book sales at the same time as HSK’s novels took a turn for the bizarre. He typically built his novels on the skeleton of an old short story from his youth, or several of them woven together. Sometimes his wife, Hazel Goodwin Keeler, would also contribute a chapter. This all became the occasion for gloriously implausible tales, chock-full of long-winded speeches in dialect; caricatures of every ethnic group from “Swodocks” to “Celestials”; near-future technology such as intercontinental 3D television; and, inevitably, a surprise ending that sends your synapses on a rollercoaster ride. This stuff appealed to an ever narrower audience. Finally, Dutton dropped Keeler in 1942. He was published by the bargain basement Phoenix Press from 1943 to 1948. Ward Lock cut him in 1953. Then he wrote for Spanish and Portuguese publication at $50 a title—or just for himself.

Fats Waller: Baby Elephant Patter

Was Fats Waller put on this earth to send up inane pop songs, or did Tin Pan Alley busy itself churning out an endless supply of vapid tunes just to feed his enormous appetite for ridicule? Either way, it wasn’t a bad deal: while he was irrepressible in his vocal shenanigans and merciless in his mockery of cornball lyrics, Waller also bestowed on assembly-line songs unwarranted beauty. His touch on the piano was like a hummingbird’s wings, like sunlight scattering on moving water. The great clown of jazz, Thomas “Fats” Waller belongs, with Oliver Hardy and Roscoe Arbuckle, to that brotherhood of fat men whose girth serves to counterpoint their buoyant grace and delicacy. His music is at once thundering, voluminous, and dainty, like the “baby elephant patter,” he invokes in “Your Feets Too Big,” or like one of Disney’s hippo ballerinas twirling on pointe.

The Crowd Doesn’t Just Roar, It Thinks: Warner Bros.’ All Talking Revolution

“Iconic” is a gassy word for a masterwork of unquestioned approval. But it also describes compositions that actually resemble icons in their form and function, “stiff” by inviolate standards embodied in, say, Howard Hawks characters moving fluidly in and out of the frame. Whenever I watch William A. Wellman’s 1933 talkie Wild Boys of the Road, these standards—themselves rigid and unhelpful to understanding—fall away. An entire canonical order based on naturalism withers.

To summon reality vivid enough for the 1930s—during which 250,000 minors left home in hopeless pursuit of the job that wasn’t—Wellman inserts whispering quietude between explosions, cesuras that seem to last aeons. The film’s gestating silences dominate the rather intrusive New Deal evangelism imposed by executive order from the studio. Amid Warner Bros.’ ballyhooing of a freshly-minted American president, they were unconsciously embracing the wrecking-ball approach to a failed capitalist system. That is, when talkies dream, FDR don’t rate. However, Marxist revolution finds its American icon in Wild Boys’ sixteen-year-old actor Frankie Darro, whose cap becomes a rude little halo, a diminutive lad goaded into class war by a chance encounter with a homeless man.

Disturbing the Peace: Florence Turner

Florence Turner was a beautiful woman, with large dark eyes and a long, fine-boned face. She was also riotously funny. A parade of gorgeous comediennes have followed in her footsteps—Mabel Normand, Constance Talmadge, Anita Garvin, Carole Lombard, Lucille Ball, Judy Holliday et al.—yet they continue to be viewed as exceptions to some unwritten rule: that women aren’t funny, that only unattractive women are funny, that being funny makes women unattractive. Even Walter Kerr, one of the greatest writers on silent comedy, dismissed female comedians as being handicapped by the necessity that they be pretty. If beauty is a handicap in comedy, Buster Keaton should never have earned a single laugh.

In Daisy Doodad’s Dial (1914), Florence Turner blows a sustained silent raspberry at this whole uncomfortable issue. This one-reel British-made comedy centers around Daisy’s determination to enter and win a face-making contest. (Your dial is your map, your pan, your puss, in other words your face.) Practicing at breakfast with her husband, in a bus with two horrified male strangers, or in a police station—after she is arrested for disturbing the peace—she pulls the most hilarious and outrageous succession of faces I have ever seen. But the funniest thing of all is the way she alternates this array of grotesques with a subtle, dignified deadpan. One moment she’s a gargoyle, a ghoul, or a goofball; the next moment she’s an elegant lady, someone who might be painted by John Singer Sargent. Turner has absolute control over every muscle of her face, and her expressions are as readable as the morning newspaper, but also witty and pithy as aphorisms.

After seeing Daisy Doodad’s Dial as part of the BFI’s magnificent compilation “A Night at the Movies in 1914” (which also includes footage of the militant suffragist Emmeline Pankhurst being hustled out of Buckingham Palace by a pair of hulking bobbies), I understood why Buster Keaton had the inspiration to hire Florence Turner to play his mother in College (1928). It’s a wonderful bit of casting—though she was in fact only ten years older than he was. They look remarkably alike, and Turner matches Keaton’s stoic deadpan beautifully.

By 1928, however, she had been completely forgotten, and by the 1930s she would be doing bit parts and extra work. Known at the start of her career as “The Vitagraph Girl,” Turner is not to be confused with Florence Lawrence, “The Biograph Girl,” who is labeled by film histories as the first movie star. Turner was perhaps the second, and was celebrated as both a comedienne and a dramatic actress. In 1912, she was voted the most popular woman in the movies. A year later she left for Britain where she formed her own production company, Turner Films. (The move was attributed to the stifling effect of the Motion Picture Patents Company, which also drove many filmmakers to abandon the east coast for Hollywood.) In 1914, she was voted Britain’s most popular female film star. She also wrote and directed some of her films, including Daisy Doodad’s Dial. Tragically, it is one of only two survivors from her British productions.

Why her career began to fade as early as 1916 seems to be unexplained. She is virtually unknown today, though many of her Vitagraph films survive. The entry on Turner in Columbia University’s online Women Film Pioneers Project whets the appetite even more. For instance: “Possibly Turner’s most demanding role was the rejected lover in Jealousy (1911), a film now lost. Promoted by Vitagraph as ‘A Study in the Art of Dramatic Expression by Florence E. Turner,’ the film was a tour de force for the actress, as she was the sole performer on-screen for the entirety of Jealousy’s running time…Moving Picture World, in August 1911, stressed the centrality of performance to the effectiveness of the film: ‘[The actress] has the courage to let the truth be told in her countenance and movements. The audience gazes into the mystery of a human soul.’”

This sounds well worth seeing, but I’m not sure gazing into the mystery of a human soul would be as much fun as gazing into Florence Turner’s face at the end of Daisy Doodad’s Dial. In a marvelous dream sequence, Daisy lies tossing and turning in bed while a parade of her own ghostly images marches past, each pulling a different wild face. You might think the film will end with her chastened and newly demure, but instead it ends with her in close-up staring directly at the camera and pulling even more faces, defiantly distorting her handsome features with rubbery zeal. A hundred years later, her message is clear.

by Imogen Sara Smith

Helen Chandler: Picon Citron

In the original or at least the first American sound version of Dracula (1931), Bela Lugosi spends a sizable portion of the film after Helen Chandler’s blood, and his pursuit of her seems more than a little misguided. Was there ever a screen performer who looked as snow white as Chandler, as anemic, as small and bloodless? She was a petite blond, a wraith, and her blue eyes were almost white in their starkness, too, so that she always seemed to be looking inward instead of out, and those small inward eyes of hers could have an unnerving quality that suits the buggy but creaky horror of this Dracula. Chandler speaks in a strained, chirping voice, and she’s very intense. Who is she, and why does she stare like that?

She was born in South Carolina, and her Southern accent comes out sometimes on screen, especially in her last film, Mr. Boggs Steps Out (1938), where her distinctively belle-like volatility makes her seem kin to Miriam Hopkins. In the 1920s, Chandler built herself an impressive career on Broadway, playing with John Barrymore in Richard III, Lionel Barrymore in Macbeth, and then as Hedvig in Ibsen’s The Wild Duck and as Ophelia in a modern dress Hamlet. Hedvig goes blind and Ophelia goes mad, and both of these extremes must have suited Chandler’s birdlike imperturbability, her sense that she lived entirely in her own world. She was a leading lady for John Ford in Salute (1929), and then she made an impact as one of the lost people on board a floating ship of the dead in Outward Bound (1930), which looks as creaky today as Lugosi’s Dracula does.

The prime year for Chandler in films was 1931. After Dracula, she played opposite Ramon Novarro in Jacques Feyder’s Daybreak, a movie where she’s asked to do an extended drunk scene: “I want another one!” she cries, when it’s clear that she’s had more than enough booze, and then when Novarro obliges, Chandler insists on “a full one.” And so when Chandler played Nikki in her finest film, William Dieterle’s The Last Flight, she had some practice with drinking on screen for one of the all-time best boozing movies and one of the all-time best romantic group movies.

Three on a Match

The title and premise of Three on a Match suggest an ensemble film, but don’t be fooled. This is Ann Dvorak’s movie, and the finest showcase for her avid, feverish energy. She was twenty years old and blazing her way through her first year as a star, starting with her electrifying turn as Tony Camonte’s insatiable sister in Scarface. Slender and elegant, with a refined beauty, Dvorak always seemed to be looking for trouble. “Somehow the things that make other women happy leave me cold,” she says in Three on a Match, explaining the gnawing dissatisfaction that a devoted husband, a cherubic son and a life of luxury can’t assuage.

The other two on the match are Joan Blondell and Bette Davis, but they are stuck with tepid roles, and even Warren William (as Dvorak’s husband) is uncharacteristically virtuous and bland. All raw nerves and dangerous luster, Dvorak makes her haughty, self-immolating character not only more interesting but more sympathetic than the nice women who profit from her fall.

Seduced by a penniless playboy (Lyle Talbot, leaving his usual trail of slime) she shacks up with him in a hotel suite, neglecting her child, and slides rapidly from champagne parties to drug-addicted poverty. The movie really starts to get good when the debt-ridden Talbot kidnaps Dvorak’s son. In a noirish sequence, they all hole up in a squalid apartment, guarded by a trio of goons led by Humphrey Bogart, who nastily mocks Dvorak’s cocaine withdrawal. Three on a Match crystallizes her daredevil glamour, while also offering a brisk, punchy warning about what happens to girls who play with matches.

by Imogen Sara Smith

Jack Black in Hollywoodland

Ex-burglar turned successful author Jack Black would do like so many writers then and now: heed that call and make the lonely journey to Hollywood. Though generally imperturbable after all he’d been through he was perhaps more surprised and pleased, and honest with himself, than most.

After all what are the chances that a three-time loser who copped a twenty-five-year jolt and fully expected to kick behind bars would find himself, after a once-in-a-lifetime jailbird’s appeal that reduced his sentence to a year, working for a San Francisco newspaper and, befriended by its editor, encouraged to write his story for publication. Well? And then a call from a movie studio rep to boot? A shot in the dark, son, and Jack took it by gosh. By the time he published his one and only book, You Cant Win, in 1926 he was about fifty-five years old. He liked to say then that he’d spent fully half his life in the underworld, either on the road, on the lookout, and on the run or else in stir. Now, though still hidden behind his name, a mask he very rarely relinquished no matter the circumstances (even in the upper world to ask would be to invite suspicion; he remained an avowed creature of the night), he was about to embark on the most eventful years of his life in the straight world.

Following the fine notices of his adventure-filled autobiography, in November of 1926 he traveled south from San Francisco to Los Angeles on a leave of absence from his position at the San Francisco Call with the hearty approval of his friend and mentor the fighting editor Fremont Older. The year to come of course turned out to be an eventful one in Hollywood, as silent movies reached their artistic peak and the first so-called talking picture would be released come October 1927.

Jack was employed as a $150-a-week writer on staff at the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer film studio. In a letter from January of 1927 written on MGM stationery he states that he is presently helping write a prison story and that it is nearly complete. Though no credits have been found* it was not unusual for three, four, half a dozen, or even more writers to be assigned to the same project, frequently simultaneously and working anonymously. Additionally, in the literalist mind of movie producers, hiring an ex-con to write about convicts and prison life is movie common sense, even if you cant use his stuff. (PR will cover his weekly.) Jack may have applied his talents as a scenarist, a dialogue or intertitle writer, or in Fitzgerald’s self-derogatory term a script clerk. (MGM crews at the time were given to likening work in the studio to that, they imagined, of laboring at the jute mill, that is, prison drudgery.)

Irving Thalberg, the skillful young production head of what was by the time Jack arrived the biggest studio in town, was a surehanded and honest to god perfectionist who tinkered knowledgeably behind the scenes in just about every aspect of the making of a picture. One of his projects in the late 1920s was The Big House, set in San Quentin, which wasn’t released, however, until 1930. It reeked of authentic locales and dialogue; his mania for getting things right no matter how many folks he disturbed along the way stands the film in good stead to this day; an Academy Award for writing was presented to the film. This was the kind of venturous man Jack could admire and it’s quite possible he worked under his aegis, if not on this picture per se.

30 For Timber

Johnny Oakes, whose mob monicker was “Timber” was in Dutch. The finger was put on him for speaking out of turn to his twist. The mob decided that, for safety’s sake, Timber must go riding. Skivers and Skats drew the job of sneezing Timber and chopping him down. Skivers and Skats were rambling down the drag when they I.Cd. Timber pushing pills in a pill-joint. They curbed the boiler and rambled into the pill-joint with their roscoes in their coat kicks and fronted Timber. They officed him out to the boiler and as soon as he hit the boiler they cleaned him of his protection. Skivers took the wheel and Skats acted as cover on Timber. Then they high-balled to the timbers and stopped and made Timber get out. Skats said, “This is curtains for you, Timber.” Timber asked why he was riding. He was then infoed that his chatter to his twist about his capers was 30 for him, and the rest of the mob said 40. Skivers said, “We’ll give you a break for your agate and let you play rabbit. If you make it, why 40; if not, it’s 30. When I give you the office scram, and we will let you make 100 before chopping. That is your only out.” Timber was given the office and scrammed for his agate, but the wipers got into action and chopped him down. 30 for Timber.

The Argot of the Underworld by David W. Maurer; American Speech, 1931

Bonus: Glossary of Harlem slang appended to Maxwell Bodenheim’s novel, Naked on Roller Skates (1930)

acecray outcray: putting the ace on the bottom of the deck, where the dealer can abstract it

bah-bah: negligible object

cake-slashing: assault and mayhem

century: hundred dollars

chippy: dissolute girl

chivvy: unpleasant odor

clip your tongue: be silent

cram the paper: cheat at cards

cut your chops: mind your own business

five hard: a fist, a punch

frill: girl, woman

glued their traps: remained silent

going to the timbers: retreating

grand: thousand dollars

grease it: pay bribe money, or blackmail

hamburger down: take it easy

hock your skin: make a difficult promise

hootch: liquor

hotsprat: trivial but agreeable entertainment

in the hole: out of money

lame your foot: deprive you of assistance

leathered: kicked unfairly

lippy chaser: a negro who prefers whites

payman, a: a cadet

pinktail: white person

scrub: face

slide them into concrete: eject them to the sidewalk

spreadeagle: to knock down

stick it: capture something

stick-stick: defeated by previous capture

stretch: jail term

three-nine: sexual variant

thumb: use the thumb to displace cards in a poker-game

trip his muscle: over-reach himself

wraps, or skins, or strips: dollars

William Attaway’s Hobo Novel

“Day O! Day O! Daylight come and me wanna go home.” Most Americans would immediately recognize Harry Belafonte’s “Banana Boat Song,” with its rhyming, rhythmic language and the irresistible calypso beat. “Come Mr. Tally man tally me banana…” Yet the creative genius behind the popular Jamaican singer is little known beyond a small academic circle. A close friend of Belafonte, African American writer William Attaway wrote the lyrics to this classic and others, compiled in his Calypso Song Book of 1957. “Day O is based on the traditional work songs of the gangs who load the banana boats in the harbor at Trinidad,” Attaway explains in the liner notes of Belafonte’s 1956 album Calypso. “The men come to work with the evening star and continue through the night. They long for daybreak when they will be able to return to their homes. All their wishful thinking is expressed in the lead singer’s plaintive cry: ‘Day O, Day O…. The lonely men and the cry in the night spill overtones of symbolism which are universal.” Attaway spent a long and varied career giving voice, in a range of literary and popular genres, to “the lonely men” whose labor puts food on our tables and keeps our industries running. He is best known for his 1941 novel Blood on the Forge, which chronicles the African American Great Migration and labor strife in the Pennsylvania steel mills.But perhaps Attaway’s most powerful expression of the loneliness of the agricultural worker is his first novella—out of print and neglected by scholars—a hobo narrative called Let Me Breathe Thunder.

Attaway’s interest in the poor and outcast began not with his own experience of poverty, but with his youthful rejection of bourgeois values that prompted him to follow an unconventional path. Attaway was born in Greenville, Mississippi in 1911, and migrated as a child to Chicago. His father, a physician, and his mother, a teacher, desired better opportunities for their children outside of the Jim Crow South, and encouraged their son to pursue a career in medicine. While his older sister, Ruth, met their parents’ expectations by studying hard and becoming a successful Broadway actress, William bristled under the constraints of his middle-class upbringing. He frequently skipped classes during high school, and fared little better at the University of Illinois—except for his course in creative writing.