Hero of Our Nation

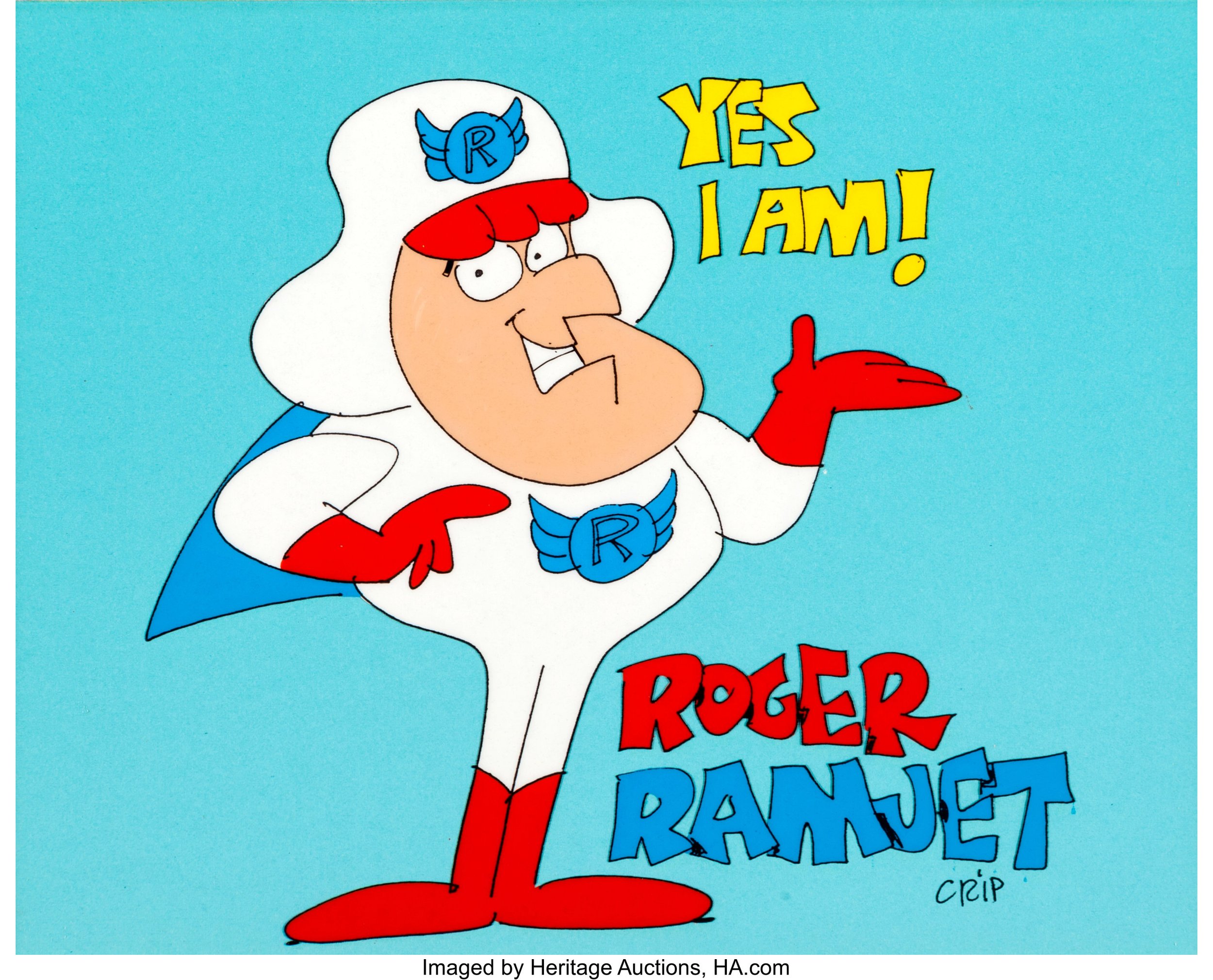

I first encountered Roger Ramjet on a Chicago public access station in 1983. It was part of an early morning show apparently aimed at stoner insomniacs. The show came on at five and also included episodes of Lancelot Link, Secret Chimp, that awful Beatles cartoon, and a weather report clarified by some appropriate pop song (“Here Comes the Sun” or “Here Comes the Rain Again”). I was usually up and around that early for some godforsaken reason, and originally started watching on account of Lancelot Link. Always did love that Lancelot Link. But Roger Ramjet was, well, let’s just say it was a revelation.

Zontar: The Thing from Venus

A study in microscopic paranoia, Zontar is one of the more outrageous products of mid-sixties UFO Fordism. Its roadkill ‘plot’ shoulders on Body Snatchers territory: An absurd papier-mache creature plans world domination by zombifying the Military Industrial Complex, beginning with a lonely SETI outpost in the Mojave. Most of the inaction takes place in clapboard rec-rooms, abutted to stock footage of missile silos and pans of a stark desert moonscape (the latter is actually a suburb of Dallas, according to the scholars). Inside their pre-fab hells, the inmates mix drinks and threaten each other, occasionally erupt in spasms of wild emotion, then settle down again to the demands of stage-bound budgeting and the confines of a constant medium-shot frame. In a performance that must have been deeply influenced by Milgram’s torture experiments, Tony Huston is especially manic and perplexing as Zontar’s first human dupe, a NASA egghead called Keith. There are hints of a deep-seated nihilism behind his near-hysteria, but seeing that he also wrote the script, maybe it’s just the glee of a strange and lonely pride. His foil is John Agar, an actor who always seems to take on the attributes of the furniture around him. He is a practitioner of Taoist wu, the necessity of presence – neither more nor less.

Zontar finally arrives on earth and sets up command and control in a cave, where he cuts a touchingly vulnerable figure. As he is quite immobile – perhaps because Agar’s salary ate up most of the budget – he is assisted by strange airborne skeet-creatures who zombify the local servicemen and townspeople by stinging them. Repetitive shots of these cardboard demons flying over telephone wires, suburban bungalows, and stalled trucks look like captures of today’s drones haunted-up in memorial black and white. This is indeed skeletal filmmaking at the margin of afternoon fever-dreams, and it has a genuinely purgatorial atmosphere of cramp and marginal reality. Zontar of Venus looks splendid: a Duk-Duk fetish, proud and pitiful in glaring fabrication and bad lighting, an abandoned nightmare decaying in front of overgrown children, waiting for the end like a Mormon angel.

Huston soon realizes that Zontar is an intergalactic fascist whose plans are not liberation but human slavery. In a climax more desperate than thrilling, he rids the universe of both Zontar and himself with something called ‘plutonium ruby crystal’ – yet one feels a terrible certainty that the ‘story’ will repeat in a never-ending informational loop. The living and the dead will again assume their places and carry out their tasks once more, until the last flickering of recorded time. This sense of cyclical production is perhaps the ghostly product of Zontar’s eternal run on rosy-hour TV for the last half–century, as if the film itself had taken on the substance of its own interminable repetition. Zontar is cousin to Milstar.

Trauma-Toons

A shortish documentary called Cartoon College, directed by Josh Melrod and Tara Wray, celebrating the Center for Cartoon Studies in Vermont, left me thinking about a bunch related or semi-related things. The (unaccredited) Center offers a two-year course leading to a Master of Fine Arts in cartooning.

First of all, is such a curriculum necessary? In the applied-arts sense, probably not really, but as a supportive place for artists doing something that, the film proclaims, society at best ignores, or at worst sneers at, it shines. Kids and adults – including a man in his late 60s – act as though they are finally being allowed to crawl out from under the carpet.

Which by the end made me uneasy. The presumably self-selecting group projects a stereotype of cartoonists as universally depressed dweebs with godawful childhoods – salvaged suicides or serial killers in waiting. Somehow, I can’t believe this is a broadly accurate cross-section of those involved in an admittedly wacky profession.

Which then led me to recall how much the newspaper comics meant to me growing up, and to a lot of kids of that era. And it wasn’t just kids reading the “funnies”; consider the sophistication and orientation of “Winnie Winkle,” “Brenda Star,” “Rex Morgan” – these were works written with an adult audience first and foremost in mind.

They were the static YouTube of the time, and their hold on me has never relaxed. Will Eisner and his seven-page Sunday adventure "The Spirit" were the highlight of my week. In the ‘70s, Eisner’s boundary-breaking foray into the “graphic novel” made my liver quiver.

The Wet Parts of the Face

Sometimes, watching a movie while insufficiently awake, random, inept idiocies will pop into my forethought: “They’re not socially distancing!” while looking at a crowd scene in a twenties slapstick short. “He shouldn’t stand so close to them when he’s talking,” during a three-handed dialogue crush in a Warners precode. It’s become second nature (which is no nature at all), this omnipresent anxiety about proximity. How will it feel when (I assume there’s going to be a “when”) I get back into the cinema.

Heavy

Long before his face became familiar to television audiences as the obese star of the long-running cop series Cannon, and long after his voice had become familiar to radio audiences as the star of everything from The Lone Ranger and Suspense to Gunsmoke and Buck Rogers, William Conrad was a busy character actor in films, bridging his earlier and later heroic roles by playing a string of killers, corrupt city officials, gangsters, and cowardly busboys, many of them uncredited, most offering him only a few brief moments of screen time, and all of them hard to forget. His smooth corpulence, thick mustache, toadish features, and resonant voice gave him a presence that made playing heavies all but an inevitability when Conrad moved from radio to screen. It also helps explain why a radio star of his magnitude (his voice was as recognizable to the masses as Orson Welles’) would be given such small roles when he made the leap. But the former WWII fighter pilot made the most of them.

The Mysterious Death of a Hollywood Director

This is the tale of a very famous Hollywood mogul and a not-so-famous movie director. In May of 1933 they embarked together on a hunting trip to Canada, but only one of them came back alive. It’s an unusual tale with an uncertain ending, and to the best of my knowledge it’s never been told before.

I. The Mogul

When we consider the factors that enabled the Hollywood studio system to work as well as it did during its peak years, circa 1920 to 1950, we begin with the moguls, those larger-than-life studio chieftains who were the true stars on their respective lots. They were tough, shrewd, vital, and hard working men. Most were Jewish, first- or second-generation immigrants from Europe or Russia; physically on the small side but nonetheless formidable and – no small thing – adaptable. Despite constant evolution in popular culture, technology, and political and economic conditions in their industry and the outside world, most of the moguls who made their way to the top during the silent era held onto their power and wielded it for decades. Their names are still familiar: Zukor, Goldwyn, Mayer, Jack Warner and his brothers, and a few more. And of course, Darryl F. Zanuck. In many ways Zanuck personified the common image of the Hollywood mogul. He was an energetic, cigar-chewing, polo mallet-swinging bantam of a man, largely self-educated, with a keen aptitude for screen storytelling and a well-honed sense of what the public wanted to see. Like Charlie Chaplin he was widely assumed to be Jewish, and also like Chaplin he was not, but in every other respect Zanuck was the very embodiment of the dynamic, supremely confident Hollywood showman.

In the mid-1920s he got a job as a screenwriter at Warner Brothers, at a time when that studio was still something of a podunk operation. The young man succeeded on a grand scale, and was head of production before he was 30 years old. Ironically, the classic Warners house style, i.e. clipped, topical, and earthy, often dark and sometimes grimly funny, as in such iconic films as The Public Enemy, I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang, and 42nd Street, was established not by Jack, Harry, Sam, or Albert Warner, but by Darryl Zanuck, who was the driving force behind those hits and many others from the crucial early talkie period. He played a key role in launching the gangster cycle and a new wave of sassy show biz musicals. At some point during 1932-33, however, Zanuck realized he would never rise above his status as Jack Warner’s right-hand man and run the studio, no matter how successful his projects proved to be, because of two insurmountable obstacles: 1) his name was not Warner, and 2) he was a Gentile. Therefore, in order to achieve complete autonomy, Zanuck concluded that he would have to start his own company.

In mid-April of 1933 he picked a public fight with Jack Warner over a staff salary issue, then abruptly resigned. Next, he turned his attention to setting up a company in partnership with veteran producer Joseph Schenck, who was able to raise sufficient funds to launch the new concern. And then, Zanuck invited several associates from Warner Brothers to accompany him on an extended hunting trip in Canada.

Larger than Life

In 1927, Albert Bertanzetti and his three-year-old son, William, were taking a stroll when they stopped to join a small crowd watching a film being shot on the streets of Los Angeles. During a break in the shoot, Albert suggested his son go show the director, Jules White, his little trick. So William toddled over to White and tugged on his pant leg. When he had White’s attention, William flipped over, went into a headstand and began spinning in circles. White was so taken with the trick he gave the young Bertanzetti a small uncredited role in the two-reel short, Wedded Blisters. Afterward, William earned a regular role in the popular Mickey McGuire series of shorts, where he played Mickey Rooney’s younger brother Billy. Taking prevailing anti-Italian sentiments into consideration, in the credits he was cited as “Billy Barty.”

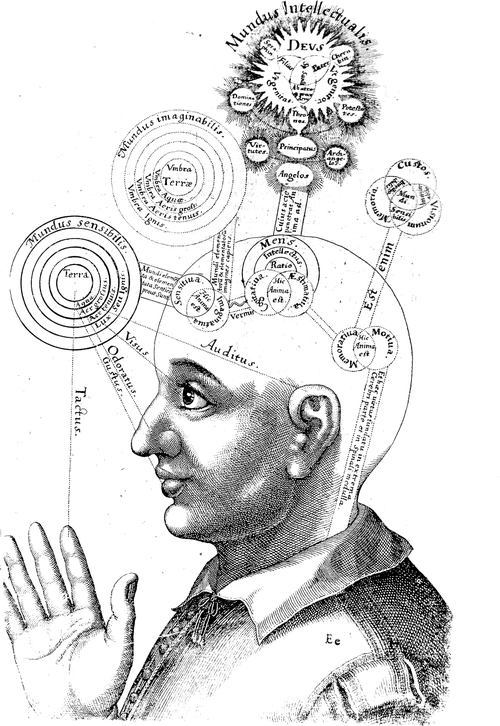

A Dodderer Looks at His Brain

When I’m out walking in our wonderful woods, I keep my head down because otherwise I’ll stumble over every rock, no matter how familiar the path. I don’t know what my feet will do next.

If I wander a few yards off the path to check out a fallen tree, then swivel slightly sideways, I’m disoriented for the first few seconds. I have no learned sense of direction.

Driving, I can’t accurately locate a knob on the dashboard. I have to feel for it or (worse) look. My body does not learn from repeated positioning. I have little of what’s now called “muscle memory.”

I have double vision and little depth perception. I can’t lay a clean line of wallboard joint compound because it requires the ability to accurately estimate a 1/8 inch-thick coating. In the kitchen, I’ll reach for a knife on the magnetic rack and slam my hand into the wall. I lumber into doorways.

Years ago, a 13-year-old housemate in our commune, one of the most extended people I’ve ever known, described her mentally precocious younger brother as “physically stupid.” That fired all sorts of slumbering neurons in my head and has stuck with me ever since. It was a brilliant observation.

Human Dialect Cocktails

White girls trying to sing like black girls is not a new phenomenon in pop music. A century and more ago, a less polite and sensitive time, such white performers were called “coon shouters.” They were in many ways the female equivalent of minstrels, and some began their careers in blackface. They sang what white folks took to be blues and jazz and rag; they belted and moaned and shimmied; they exuded raw desire and humor, and generally performed in ways white folks thought black folks did. Just as the first minstrels, primarily of Irish or German descent, passed the form down to mostly Jewish ones by the 1900s, coon shouters of the twentieth century tended to be Jewish. It was entry-level schtick, especially for those who in one way or another didn’t conform to contemporary standards of stage pulchritude.

May Irwin was one of the first coon shouters, and helped set a pattern followed by many others. Born Ada Campbell near Toronto in 1862, she was large and fleshy even by expansive Victorian standards, with a milk-and-roses complexion that showed her Irish heritage. She and her sister Georgia, who took the stage name Flo Irwin, became a singing sensation at Tony Pastor’s variety theater in the mid-1870s. They split up in the 1880s, and May went on to belt out coon songs both in blackface and not. “The Bully Song,” her biggest hit, begins: “Have yo’ heard about dat bully dat’s just come to town/ He’s round among de niggers a-layin’ their bodies down.” She performed it in a Broadway musical review of 1895, The Widow Jones, which also included a lingering kiss with her co-star. Thomas Edison caught the show and got the stars to come to his studio, where he filmed The Kiss. The first recorded osculation in American cinema, it’s only twenty seconds long and they actually talk and giggle more than they kiss, but it was denounced anyway by moralists who were already seeing film as a tool of the devil. Like many coon shouters after her, Irwin was as noted for her comic skills as for her singing and her sexy scandals.

John Ericsson, Ornery Inventor

When the Civil War started, much of the small and antiquated U.S. Navy was in dry dock at Norfolk’s Gosport Navy Yard, which was now behind enemy lines. Rather than let the Confederates seize the ships, the commander scuttled and burned them on his way out. Among the charred wrecks was the Merrimac, which had been a big, sleek steam-and-sail frigate bristling with forty guns. Originally its name was spelled “Merrimack” for the New England river, but it somehow lost the k. The Confederates conceived a bold plan to refloat her, repair her, and sheath her hull in iron, with a massive battering ram fitted to the prow, to create a “floating battery.” She would make everything in the Union navy obsolete.

But the Confederacy was very deficient in the sort of iron works and workers who could pull this off, southern states having always depended on the industrialized north for such projects. It would be almost a year before the dreadnought was ready to fight. This gave the Union ample time to come up with a response. Reluctantly, Washington turned to a brilliant, sometimes fanatical and often quarrelsome designer and inventor in New York City, John Ericsson.

He was born in Sweden in 1803, son of a mining engineer who recognized him as a prodigy early on. By twenty-three Ericsson was in London, the roaring heart of the Industrial Revolution, inventing and designing a variety of machines. He moved to New York City at the end of the 1830s, settling in today’s Tribeca in a townhouse on Beach Street, most of which is now called Ericsson Place. In 1843 the U.S. Navy launched the Princeton, a revolutionary new warship Ericsson designed with a coal-fired steam engine, a rotary screw propeller, and a gun that could launch a 225-pound shell five miles with deadly accuracy. In February 1844 the navy was proudly showing it off to President John Tyler and some four hundred dignitaries when an innovative new cannon – not of Ericsson’s design – exploded, killing the secretaries of state and the navy, a couple of sailors, and one of Tyler’s slaves. The President and his bride-to-be Julia Gardiner (of Gardiner’s Island at the forked tip of Long Island) narrowly escaped destruction. The Navy laid the blame on Ericsson, and he spent the next several years in courtrooms trying to clear his name, while also suing infringers of his propeller patent. It all turned him into an infamously ornery cuss.

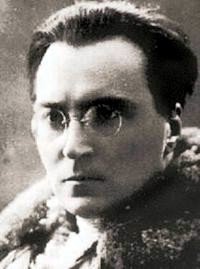

Anarchists-Bandits

On January 23, 1909 two anarchist illegalists carried out a robbery at a factory on Chestnut Road in Tottenham, in the course of which two people were killed, including a policeman. Amid their flight both anarchists shot themselves rather than surrender, one of them fatally. This event -– popularly known as the Tottenham Outrage – prefigured the 1911 Siege of Sidney Street and the crime spree of the French Bonnot Gang, where all of the participants were anarchists, and all of them bandits.

Last week the dailies related in detail a tragic incident of the social struggle. In the suburbs of London (in Tottenham) two of our Russian comrades attacked the accountant of a factory and, pursued by the crowd and the police, held out in a desperate struggle, the mere recounting of which is enough to make one shiver…

After almost two hours of resistance, having exhausted their munitions and wounded 22 people, three of them mortally, they reserved their final bullets for themselves. One, our comrade Joseph Lapidus (the brother of the terrorist Stryge, killed in Paris in the Vincennes woods in 1906) killed himself; the other was captured, having been seriously wounded.

Words seem powerless to express admiration or condemnation before their ferocious heroism. Lips are still; the pen isn’t strong enough, sonorous enough.

Nevertheless, in our ranks there will be the timorous and the fearful who will disavow their act. But we, for our part, insist on loudly affirming our solidarity.

We are proud to have had among us men like Duval, Pini, and Jacob[1]. We today insist on saying loudly and clearly: The London “bandits” were our people!

Cherry Bombs

Following the death of their parents and the desertion of their two brothers in the early 1890s, the five sisters of the Cherry family—Ellie, Lizzie, Addie, Jessie and Effie—found it impossible to maintain the family’s small and arid Iowa farm. In need of money and wanting to take a trip to Chicago, in 1893 the sisters decided to take a cue from Andy Hardy and put on a show.

Having been raised strict fundamentalists, the sisters wrote a few melodramatic sketches, a few patriotic and religious numbers, rehearsed a dance number or two, and prepared a couple recitations, which they then put together into a full show which they performed in a local hall for an audience made up of their neighbors.