“John Doe”, Alias God

On September 13, 1936, a man who called himself God led a parade of three thousand “angels” over ninety blocks south from the Kingdom of Heaven at 20 West 115th Street in Harlem.

God sat in a vintage automobile while young ladies in jodhpurs, derby hats and vivid green sashes danced and chanted to the music of kazoo-players and upright piano. God later made a speech in Madison Square Park.

God went by the name Father Divine, who ran the Peace Mission Movement from a five-story headquarters where today stands the Martin Luther King, Jr. Towers. A sign outside declared: “The abundance of the fullness occupies the entire area of this office; therefore, there can be no loitering.”

Father Divine was a rousing preacher, owned vast real estate, forbade smoking, drinking and sex, and evaded several attempts at criminal conviction by white authorities. He arose from an errant root-and-branch pulpiteer living in the Pigtown waterfront ghetto of Baltimore, to buying a mansion in Hyde Park across the Hudson River from President FDR.

Harlem in the roaring twenties was a scene of artistic revolution, where Fats Waller smashed thirds and Claude McKay heard “the halting footsteps of a lass,” but in the 1930s the neighborhood was a theater of political awakening, where Communists, union bosses, black intellectuals and cult preachers vied for a voice on the squawk tub. Father Divine acknowledged support from the Communists, but with the caveat that “just what the Communists have been trying to get you to see and do and be, I have accomplished.”

God was born George Baker, Jr. in 1879, in Rockville, Maryland. His family shared a small cabin of fourteen people, including the family of Luther Snowden, the only black landowner in the county. White religion in the area was chiefly Catholic, Jim Crow laws were brutal, and the local black neighborhood was called Monkey Run. When Baker was 18, his mother Nancy, a former slave to a tobacco planter, died. She was five feet tall and weighed 480 pounds.

Israel’s War Is Not Just Against Hamas

At one time, the ‘Arab-Israeli Conflict’ was Arab and Israeli. Over the course of many years, however, it was rebranded. The media is now telling us it is a ‘Hamas-Israeli conflict’.

But what went wrong? Israel simply became too powerful.

The supposedly astounding Israeli victories over the years against Arab armies have emboldened Israel to the extent that it came to view itself, not as a regional superpower, but as a global power as well. Israel, per its own definition, became ‘invincible’.

Such terminology was not a mere scare tactic aimed at breaking the spirit of Palestinians and Arabs alike. Israel believed this.

Watch the Skies!

Two items remain, for now, on the agenda of All God’s Chil'ren:

First, we must kill capitalism. Whether by means fair or foul, few should deny that it needs doing. Next, if human life is to survive beyond the sun’s engorgement within the next six billion years, it has become imperative for mankind (which still means us) to establish a series of exo-planetary colonies – not unlike those luxurious Galt’s Gulch hideaways in outer space that, it is darkly rumored, our billionaire class has been busily planning to remove themselves to once life on earth gets truly hairy.

Of the two, the latter goal will be achieved first so, personally, I would settle for a modest, progressive shift in our labor markets. But even that objective, modest and progressive as it may be, is one helluva stretch in these United States.

When the AFL-CIO was founded in 1955, a decent chunk of salaried and wage-earning Americans, 35% of them, belonged to a union. When we contemplate our measly and steadily falling 10.5% unionization today, that 35% becomes nothing for anyone to sneeze at. Sadder still to contemplate are the 85% of American workers gamely attempting to survive on the mean streets of a shaky private sector, where an even less significant 6.4% currently enjoy the benefits of organized labor.

So what happens to the beleaguered American Worker as collective bargaining, the Royal Road to fair and dignified compensation for all, narrows into a glass-strewn footpath, flanked by razor-wire?

Stay tuned to this frequency …

by Daniel Riccuito

Their 911

Israel has been engaging in a project of ethnic cleansing against Palestinians since its inception. It waxes and wanes in intensity and speed, but is the necessary starting point of any discussion of Israel and Palestine, or of Palestinian uses of violence. We are currently watching Israel, in an eerie replay of post-9/11 bloodlust, launch a new chapter in this project. They are indiscriminately laying waste to homes, neighborhoods, and even against caravans of those refugees already fleeing the onslaught. North Gaza will become a new Golan Heights, a de facto annexed military zone of occupation. Just as 9/11 was quickly seized upon by the neoconservatives of the Bush administration to justify enacting the Project for a New American Century’s goal of “remaking of the world” (in Afghanistan, Iraq, etc.) for American hegemony, the hardline architects of a “Greater Israel” are no doubt seeing this as their time to push through their military and political goals.

What is particularly deranged in the US is how “this is their 9/11” is being used as a justification of this looming bloodbath rather than as an ominous warning of what a disaster for humanity this military blitz against a city of mostly children will be. Rather than a cause for temperance and self reflection on the relationship between colonialism and reactions to it, it is being discussed in mainstream tv and print media as a temporary period of impunity to, what, blow off steam? It speaks volumes of the lessons Americans have not learned about the moral calamities and character of their own political institutions. Of course, this ignorance is not endemic but is also the product of intense efforts at rewriting history.

by James Petrocelli

Italian Gothic Horror: A Word from Roberto Curti

The Chiseler: At the moment, I'm immersed in your wonderful book Italian Gothic Horror Films, 1957-1969. Gothic Horror has a particular resonance for you — or am I wrong to assume?

Curti: Well, it certainly is a fascinating field. I’m not particularly into horror cinema as of now, but I used to be. I remember watching the Corman/Poe films on Italian TV as a kid, and being blown away by them (particularly The Premature Burial). When I was a teen I became an avid horror movie collector, recording whatever I could catch on TV, and never missed a horror movie when it came out in my town. But at a certain point, let’s say early 2000s, I got fed up with the genre and stopped following every new release; I stil try to keep up to date but I can’t deny the fact that my tastes changed over the years, and now I’d more gladly revisit a film by Ferreri or Monicelli than pay the ticket to watch the new Insidious or Saw.

But Gothic horror, and in particular Italian Gothic, is an interesting field of research, for various reasons, relating to the Italian film industry, but also cultural and sociological ones.

The Chiseler: Regarding gothic-themed movies: are there any characteristics typical of Italian entries to the genre that distinguish directors like Bava, Freda and Cottafavi from their counterparts in other countries?

Curti: For once, it was some sort of lab experiment since there was no horror movie tradition in the country for several reasons, and many classic Hollywood horror movies (such as Browning’s Dracula) did not arrive in Italian theaters. so, Riccardo Freda’s I vampiri (which by the way is the subject of a monograph I wrote for PS Publishing’s Electric Dreamhouse series, coming out hopefully by the end of 2023) was a true novelty in the Italian landscape, so much so that it was ultimately tampered with and partly lost its original power. But what followed next, after the success of Hammer’s Dracula, was amazing: Bava, Freda, Margheriti, Barbara Steele, etc. The Gothic made in the 1960-1966 season, which we usually consider the heyday of Italian Gothic, had a neat Italian imprint. Even if they were products designed mainly for export, they revised the genre in such a peculiar manner that they are unmistakably Italian. You can see it in the details, and in the themes. A certain way of approaching the Fantastique, for instance: as Bava once famously said, Italian don’t believe in vampires, because the Mediterranean sun would chase them away. But Italians, in the late 1950s, were quite scared (and also intrigued, of course) by the way women were becoming emancipated while the patriarchal family was disintegrating. Take a classic from 1960, say La dolce vita, or Rocco e i suoi fratelli, and then La maschera del demonio: you’l see the same attitude. Marcello is spellbound by Anita Ekberg bathing in the Trevi fountain just like John Richardson is by the sight of Barbara Steele. In Visconti’s film, Renato Salvatori viciously stabs the woman he loves, a prostitute played by Annie Girardot, out of jealousy, because he can’t have her all for himself. And in Danza macabra the macho played by Giovanni Cianfriglia kills Steele’s character for a similar reason.

In Italian Gothic the female characters often mirror the male’s incapacity of going beyond the image of woman as an angel or a whore. The Gothic depicts a transgression, but it usually provides a return to order, a punishment, in line with the nation’s Catholic background. But at the same time it hints at the contradictions of a society that was rapidly changing, with the discovery of eroticism as a mass product and a (often naive) sexual curiosity that became one of the main drives in the film industry, while the grip of censorship were gradually loosening.

Seeing and Unseeing Violence in Palestine

Violence is horrible. Condemning the violent flashes of resistance from an oppressed and occupied people without first and primarily demanding an end to the greater forms of sovereign and structural violence that initiated and sustain that oppression is also profoundly hypocritical. It is a cry for peace in service of greater violence.

The Israeli state, its military checkpoint system, and its settler apparatus have been overtly murdering Palestinians at exponentially higher rates than anything Palestinians have done to them, and have done this every single year even outside of "wartime" (which is just a difference in degree of brutalization, rather than in kind) since its creation. This includes the casual murder of journalists, women, children, and the elderly, which news anchors in the U.S. suddenly care very much about. On top of this is the near-total economic collapse, resource theft, water shortages, food shortages, medical shortages, restrictions on movement, and other forms of structural violence intentionally engineered by Israel's policies that kill untold numbers of Palestinians every day (especially in Gaza), with or without the presence of Israeli soldiers.

Marlene Against the Wall

Dishonored was Marlene Dietrich’s second Hollywood film with her diminutive Svengali Josef Von Sternberg, but unlike Morocco, her first, it tanked at the box office. It’s difficult to see why, since it’s a more involving and dramatic work than the earlier film: maybe audiences turned out for the North African adventure out of curiosity, to see this vaunted new star in the Paramount firmament, didn’t enjoy the experience, and stayed away from her second venture into languor, exotic romance and tragedy?

The movie is essentially a re-telling of the Mata Hari yarn, with Sternberg providing the original (?) story. True, the leading man this time is a considerable step down from “long drink of water” Gary Cooper. Victor McLaglen does actually look surprisingly like a leading man here, for those who know him mainly as loutish comic relief in John Ford westerns. Until he grins. And he grins all the time. I mean all the time. It’s a manic, vulpine grin expressing explosive, demented self-satisfaction and projecting a barely-suppressed urge to tear apart his co-stars and the set walls with those pearly and seemingly filed-to-a-point teeth. I’ve shown his performance to students. “Who is THAT?” they all ask, terrified. “Why is he DOING THAT with his FACE?”

Teach Your Children Well

Fourteen years after the Soviet Union detonated its first A Bomb, twelve years after Arch Oboler ushered in the era of nuclear annihilation cinema with Five, four years after Stanley Kramer offered what was supposed to be the last word on the subject with On the Beach, a year after the Cuban Missile Crisis, and a year before Strangelove and Fail-Safe, Frank Perry made a little no-budget, no-frills picture that said more about the real psychological toll of the Cold War than any other film in the very crowded subgenre of nuclear annihilation films, and said it more powerfully. And all without a single mushroom cloud. Not surprisingly, 1963’s Ladybug, Ladybug, his existentialist bummer of a film was ignored at the time and remains all but completely lost and forgotten today.

Perry’s first feature, 1962’s David and Lisa, was a sincere and emotional melodrama about a mentally unbalanced teen who finds true love in the asylum. Things took a much bleaker turn in his second feature, though given the prevailing atmosphere you can understand why.

The plot is deceptively simple, and at times can feel like an extended episode of The Twilight Zone. When the Civil Defense alarm begins blaring unexpectedly in the main office of a small rural Middle American grade school, no one knows what to make of it. The scheduled weekly alarm test had taken place a few hours earlier, which means this new siren is either a false alarm resulting from some mechanical glitch, or an honest-to-god warning the missiles were on their way and would strike in less than an hour. Tensions are only ramped up when all the phone lines to all the authorities who could set the matter straight are tied up. There was nothing about the impending apocalypse on the radio, but maybe word simply hadn’t gotten out yet.

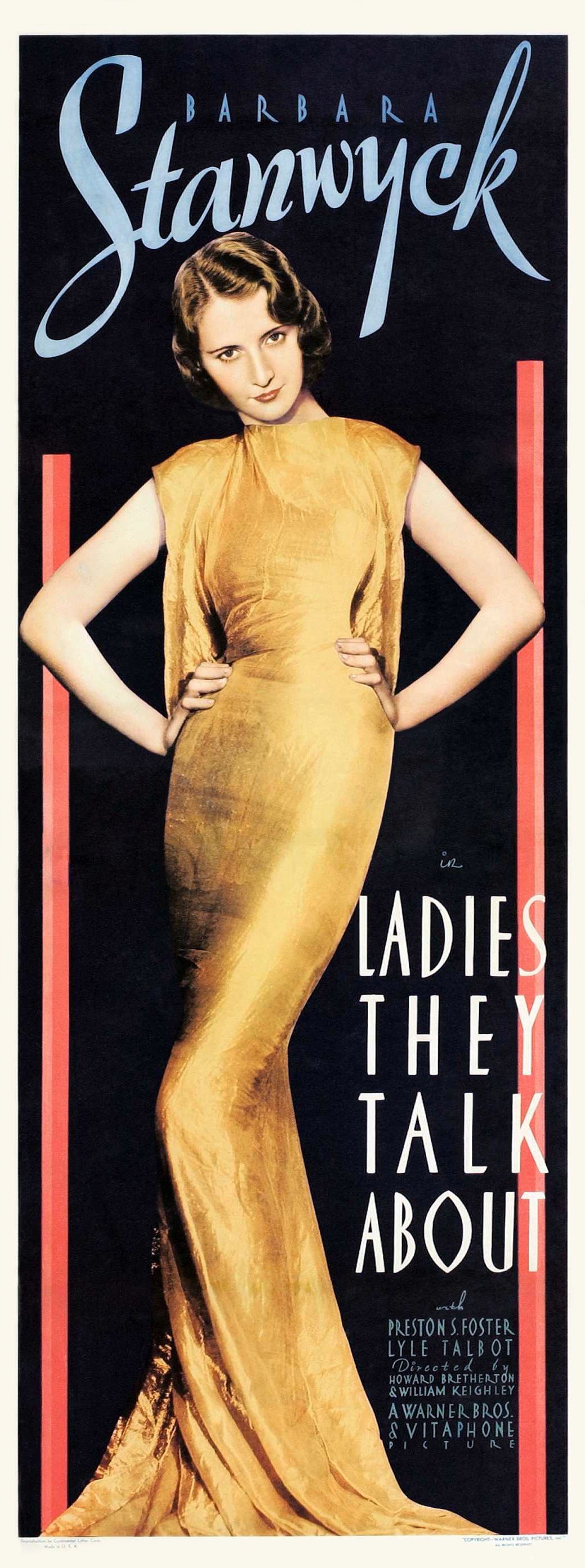

Ladies They Talk About

Who knew prison was this much fun? On a typical night in the women’s ward at San Quentin, a society dame who put ground glass in a rival’s soup cuddles her Pekingese; a madam reminisces about the “beauty parlor” she used to run; and a creepy religious fanatic dons black lingerie to listen to her idol, a radio evangelist. Meanwhile, the bubbly Lillian Roth croons, “If I Could Be With You” to a photo of…Joe E. Brown, and a cigar-smoking lesbian (“Watch out for her, she likes to wrestle,” a new inmate is warned) does weight-lifting exercises. This is less a jail than a clubhouse for deviant gals. Remorse? Repentance? Don’t make them laugh.

Especially not Barbara Stanwyck, a glamorous bank robber doing two to five for her role in a heist. Sardonic, jaded and immune to sentiment, she saunters around the hoosegow chewing gum and handing out stinging put-downs. A straight-arrow reformer (the object of the religious fanatic’s crush, and the human equivalent of a bowl of tapioca pudding) falls hard for Stanwyck and pursues her adoringly—even after she shoots him in the arm. This pairing of a bad girl and a virtuous male redeemer is a welcome reversal of the usual trope. The greatest gulf between pre-Code and film noir is that the former is so tolerant, and the latter so punitive toward women who break the rules. Like defense attorneys, these movies argue that the ladies’ circumstances should be taken into account: the toughness of their world, their limited options. And from the witness stand they use everything they’ve got: anger, tears, wisecracks and killer gams. What jury would find them guilty?

by Imogen Sara Smith

All the World’s a Stage

In 1988, a socio-linguist at the university of Pennsylvania posted a note on the departmental bulletin board announcing she had moved her late husband’s personal library into an unused office. Anyone who wanted any of the books should feel free to take them. Her husband had been the chair of Penn’s sociology department. They’d married in 1981, and he died the following year at age sixty. Normally you’d expect the books and papers to be donated to some library to assist future researchers, but she’d recently remarried, so I guess she either wanted to get rid of any reminders of her previous husband, or simply needed the space.

At the time my then-wife was a grad student in Penn’s linguistics department, and told me about the announcement when she got home that afternoon.

Well, had this professor’s dead husband been any plain, boring old sociologist, I wouldn’t have thought much about it, but given her dead husband was Erving Goffman, I immediately began gathering all the boxes and bags I could find. That night around ten, when she was certain the department would be pretty empty, my then-wife and I snuck back to Penn under cover of darkness and I absconded with Erving Goffman’s personal library. Didn’t even look at titles—just grabbed up armloads of books and tossed them into boxes to carry away.

As I began sorting through them in the following days, I of course discovered the expected sociology, anthropology and psychology textbooks, anthologies and journals, as well as first editions of all of Goffman’s own books, each featuring his identifying signature (in pencil) in the upper right hand corner of the title page. But those didn’t make up the bulk of my haul.

There were Catholic marriage manuals from the Fifties, dozens of volumes (both academic and popular) about sexual deviance, a whole bunch of books about juvenile delinquency with titles like Wayward Youth and The Violent Gang, several issues of Corrections (a quarterly journal aimed at prison wardens), a lot of original crime pulps from the Forties and Fifties, avant-garde literary novels, a medical book about skin diseases, some books about religious cults (particularly Jim Jones’ Peoples Temple), a first edition of Michael Lesy’s Wisconsin Death Trip, and So many other unexpected gems. It was, as I’d hoped, an oddball collection that offered a bit of insight into Goffman’s work and thinking.

Against Organization

We cannot conceive that anarchists establish points to follow systemically as fixed dogmas. Because, even if a uniformity of views on the general lines of tactics to follow is assumed, these tactics are carried out in a hundred different forms of applications, with a thousand varying particulars.

Therefore, we don’t want tactical programs, and consequently we don’t want organization. Having established the aim, the goal to which we hold, we leave every anarchist free to choose from the means that his sense, his education, his temperament, his fighting spirit suggest to him as best. We don’t form fixed programs and we don’t form small or great parties. But we come together spontaneously, and not with permanent criteria, according to momentary affinities for a specific purpose, and we constantly change these groups as soon as the purpose for which we had associated ceases to be, and other aims and needs arise and develop in us and push us to seek new collaborators, people who think as we do in the specific circumstance.

When any of us no longer preoccupies himself with creating a fictitious movement of individual sympathizers and those weak of conscience, but rather creates an active ferment of ideas that makes one think, like blows from a whip, he often hears his friends respond that for many years they have been accustomed to another method of struggle, or that he is an individualist, or a pure theoretician of anarchism.

It is not true that we are individualists if one tries to define this word in terms of isolating elements, shunning any association within the social community, and supposing that the individual could be sufficient to himself. But ourselves supporting the development of the free initiatives of the individual, where is the anarchist that does not want to be guilty of this kind of individualism? If the anarchist is one who aspires to emancipation from every form of moral and material authority, how could he not agree that the affirmation of one’s individuality, free from all obligations and external authoritarian influence, is utterly benevolent, is the surest indication of anarchist consciousness? Nor are we pure theoreticians because we believe in the efficacy of the idea, more than in that of the individual. How are actions decided, if not through thought? Now, producing and sustaining a movement of ideas is, for us, the most effective means for determining the flow of anarchist actions, both in practical struggle and in the struggle for the realization of the ideal.

Sabotage

Emile Pouget (1860-1931) spent his political life on the revolutionary syndicalist wing of the French working-class movement. Never frightened of revolutionary violence, he was arrested in 1883 and spent three years in prison for a riot that resulted in the pillaging of three bakeries (a riot at which Louise Michel was also arrested) . He was most famous for his newspaper and almanac called Le Père Peinard, which advocated not just syndicalism, but direct action by the workers, principally in the form of sabotage, which he was even able to get the Confédération Générale du Travail to adopt as an officially sanctioned tactic. This article is from the 1898 edition of his almanac.