Success is a Racket

The room is windowless and bare except for a table under a low-hanging lamp with a naked bulb. It’s the kind of room where only bad things can happen. A pack of tough cops gathers around the table, encircling a hapless innocent whom they plan to frame for a murder. One cop reaches up and shoves the hanging lamp so it swings back and forth, round and round, making shadows of men lunge and shudder on the walls and hot light pulse on the pale, nervous forehead of the victim. No one speaks.

Karl Freund, already the cinematographer of Metropolis and The Last Laugh, may not have invented the swinging lamp effect here, in the pre-Code Afraid to Talk (1932), but he exhibits near-total mastery of noir lighting almost a decade before the noir cycle would begin. (Swinging lamps would reappear in Crossfire, Desperate and other films, always evoking the menace of imminent violence.) This relentless drama of civic corruption—which can hardly be called an exposé, since it assumes a general knowledge that everyone in power is a crook—deserves the label of proto-noir, though it also illustrates the gaps between pre-Code and noir.

Afraid to Talk is almost gleeful in its boundless cynicism, almost sadistic in the way it dwells on men of power smirking and chortling as they torment their powerless pawns. The bad sleep well, and they have a lot of fun, too. There are few scenes in either pre-Code or noir as shocking as the one in which boyish Eric Linden—one of the “Gee, that’s swell” brand of male ingenues—is beaten to a pulp until he finally offers a false confession. The beating takes place off screen: we hear it while watching a couple of men taking a break from pounding the kid (they turn out not to be real cops, but hired thugs of the District Attorney) washing their hands, Pilate-like, and complaining that their coffee is cold. Afterward, we hear that the victim is spitting blood, has internal injuries, and was beaten on the soles of his feet. (Not too smart, since the D.A. tries to claim he was injured resisting arrest!) When one of the more squeamish thugs expresses discomfort at what they’ve done, the others sneer at him: “Are you turning pansy on us?” and dismiss his guilt with a shrugging, “It’s all in the game.”

Linden is Eddie Martin, a bellboy who had the bad luck to be in the room when a racketeer was bumped off, and the worse luck to be a convenient fall guy when the corrupt party bosses need to convict someone, but can’t touch the real culprit because he’s blackmailing them with evidence of their colossal malfeasance. While Eddie’s fate is cruel, the film is anything but glum. It’s full of wild parties, drunken women in evening gowns dancing on table tops, and fractured, swirling montages of speakeasy life. The big boss of the party doesn’t just have a bar behind a swiveling bookcase—when he pushes a button, a panel slides out of the wall and there’s a bartender standing behind it, already shaking a cocktail. (Does the man live in this cubbyhole? Anything for a job, presumably.) And in the film’s most memorable image, racketeer Jig Skelli (Edward Arnold), celebrating his release from jail at a party in a private room, draws aside the deco-patterned curtains of a picture window to reveal the floor of a nightclub, where a line of chorus girls enters dressed as chain gang prisoners, a delirious conflation of two of the Depression’s iconic images. I Am a Fugitive from a Floor Show.

Ballyhooing John Strausbaugh

Award-winning history writer John Strausbaugh tells fascinating stories about the past, bringing fresh perspectives to events and characters great and small. Open this post for links.

Skyscraper Souls

The Grand Hotel formula is stripped of romance and transported to an imaginary skyscraper that towers above the Empire State Building. Warren William is the building’s visionary developer, David Dwight, whose ego stands even taller than the monument he has built to himself, and whose charm is dangerously hard to distinguish from his amorality. His colossal achievement, an art deco Tower of Babel, justifies betrayals and cruelty. After pulling a double cross by manipulating the stock market, he points out to his outraged associates that if they were benefiting from his chicanery instead of losing their shirts, they would call him a financial genius.

His machinations cause a stock bubble that wipes out nearly all the other characters, a miniature parable of the Crash that leads to robbery and death, disillusionment and self-discovery. The skyscraper’s souls include an innocent small-town girl (Maureen O’Sullivan), an obstreperously eager young go-getter (future director Norman Foster), a prostitute, a jewelry-store owner, a radio announcer , an unfaithful wife, and Dwight’s intelligent, loyal secretary and mistress, who is no longer youthful enough to hold his interest.

Name That Anarchist

Giuseppe Zangara was a short, sickly, poor immigrant who saw capitalists as the root cause of his troubles. In 1933, when newly-elected president Franklin Roosevelt stopped to give an impromptu speech from the back of his open-topped car, Zangara decided to take care of that part of his problem. Short as he was, he had to stand on a chair to get a clear shot, which made him easy to spot and grab. He still fired five times, missing the President, but hitting four others, killing Chicago Mayor Cermak. He was sent to the electric chair, hating capitalists to the very end.

by Jim Knipfel

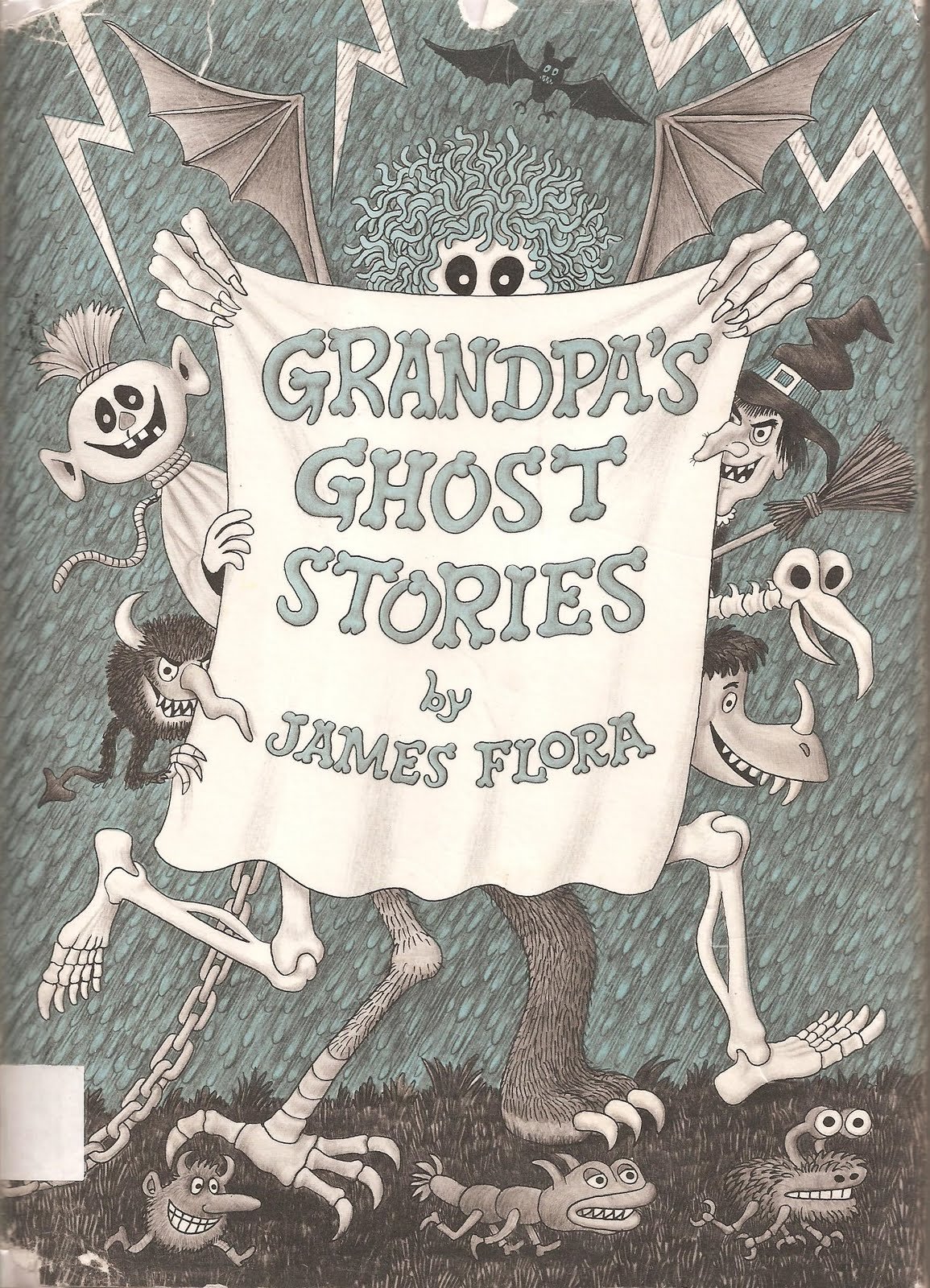

Jim Flora’s Ghost Stories

In the 1940s and 1950s, Ohio-born artist James “Jim” Flora’s whimsically disturbing pre-psychedelic cover art for countless jazz and classical albums was unmistakable. With a few heavy shades of Breughel and Hieronymous Bosch in a Pop Art context, his covers for RCA and Columbia releases featured, among other things, wild caricatures of Tommy Dorsey and Benny Goodman with multiple arms, a few too many eyes, in general at least three legs and skin patterned like fabric. In later years his artwork, which has been described as “mischievous,” “diabolical” and “sinister” would go on to grace the pages of numerous publications ranging from LIFE and Collier’s to a several-year stint painting covers for Computer Design magazine.

Unlikely as it seems considering his mind-twisting style, between 1955 and 1982, while working closely with famed children’s book editor Margaret McElderry, Flora would also write and illustrate seventeen children’s books, including The Fabulous Firework Family, The Day the Cow Sneezed, Pishtosh, Bullwash & Wimple, and Charlie Yup and his Snip-Snap Boys.

Over the years most of Flora’s children’s books would be rediscovered on a regular basis, save for one.

Originally published by Atheneum Books in 1978, Grandpa’s Ghost Stories was never republished, not by Atheneum and not by anyone else. In fact it was occasionally even left off bibliographies of Flora’s work. You have to wonder if, that first time around, it left too many impressionable kids with too many emotional scars.

History of Gaza: On Conquerors, Resurgence and Rebirth

Those unfamiliar with Gaza and its history are likely to always associate Gaza with destruction, rubble and Israeli genocide.

And they can hardly be blamed. On November 3, the UN Development Programme and the UN Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA) announced that 45 percent of Gaza’s housing units have been destroyed or damaged since the beginning of the Latest Israeli aggression on Gaza.

But the history of Gaza is also a history of great civilizations, as well as a history of revival, rebirth.

Fate and Necropolitics in Gaza

It is hard to stomach images of the catastrophic ethnic cleansing Israel is committing against Palestinians in Gaza. Thousands are dead, including thousands of children. Half of the residential buildings are uninhabitable or rubble. Public facilities are destroyed. There are tanks on the street. All basic necessities are gone or on the verge. Ghoulishly, Netanyahu has announced that this is only the beginning.

Necropolitics is the term Achille Mbembe gives for the ways in which states deploy power to determine how people live and who must die. Whole populations and categories of people are thrust into conditions of precarious or even doomed existence, on the precipice of disaster from the legacies of colonialism, neoliberalism, climate change, disinvestment, policing, structural violence, and war. The predictable police murders and early deaths of Black and Indigenous Americans, the mass casualties of some pseudo-natural disaster Over There, the everyday violence of sweatshop labor in the Global South, the entire nations doomed to be climate victims and refugees in the coming century... these are not accidental distributions of death, but rather are governed.

One of the most chilling aspects of necropolitics is the way in which feelings of necessity and inevitability are engineered in relation to this distribution of death. Our perception of time is altered, becoming a vehicle to cart us into that charnel house future. When Israel announces that its “right to defend itself” – and its position of domination over a colonized population – is so paramount, so eternal, that entire cities have to be leveled, what can Palestinians do but die? When Israel informs families ahead of time that it will be destroying their community in the near future, how can it be anything but the Palestinians’ fault for continuing to live where Israel must bomb? How can the claims of mere mortal Palestinians ever compete with the immortality demands of the Israeli state? No, the Palestinians must be the problem, and must be cut to fit the Procrustean bed of Zionism.

Volumes of Light: Books, Movies and Bodily Transformation

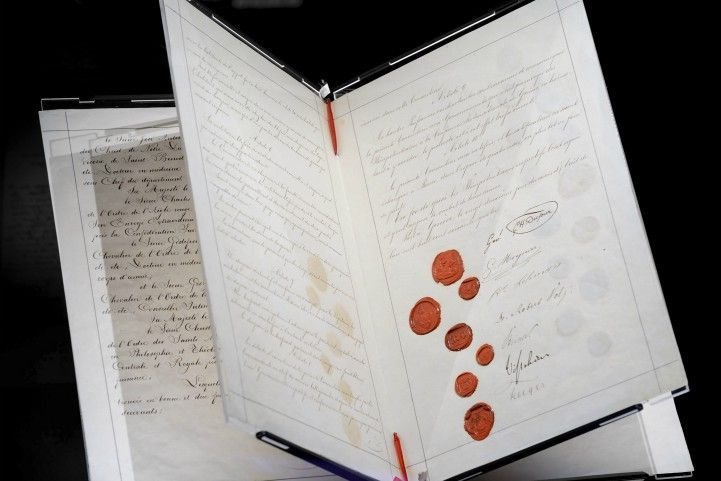

It is the custom of illuminated manuscripts to transform sacred words into shimmering icons which break, easily, beyond the sensory limitations of simple text, rendering ordinary letters into evocative, animate visual form that invites the eye to idle awhile at the brink of transcendence, rather than stand at a distance, remote and unyielding, daring to be comprehended, accepted, believed. Strange and barely recognizable wildlife appears on vellum leaves, creatures that wind and unwind in ceaseless whirlpools of bejeweled abstraction. Or they are, if you prefer, the spirited exoskeletons of snakes, dragons, waterbirds — Celtic and Germanic obsessions meeting the Apostles of Christendom. Emerging in the British Isles between 500–900 C.E., The Lindisfarne Gospels provide an arena, lapidary and starlit, where paganism devours Christianity while also birthing the religion anew into what can only be described, if you're honest, as “motion pictures”.

Put simply movies are books, volumes of light, zoetic leaves and letters that move beyond their trellis, leaving us to decipher a purely visual enigma; all the more impossible to contain within mortal consciousness because the light of this steadfastly irrational art has swallowed up the text. There are those, however few in number, who have claimed to decode this cryptic iconography. But mysteries remain, not unlike those — strange, delved, bewildering — contained within the gospels.

These mysteries urge upon us a wholly radical reconsideration of silent cinema, of the book in film, of whispering pages. Pages fluttering like leaves. Of Stan Brakhage, who gave us a series of works entitled The Book of Film — yet otherwise seemed incapable of regarding the universe independent of its sensual properties. Of Hollis Frampton and Peter Greenaway and even Wes Anderson, and certainly of Robert Beavers, who incorporates the sound and motion of turning pages, placed in relationships and analogies with other actions, as with the moving of birds' wings in flight. The films of David Gatten, which deeply engage with the idea, even the history of books.

Letter from a Senate Staffer

Dear Senator,

It has been one of the greatest honors of my life to serve the American people in your office. Many days, I wake and reflect on my fortune to be working at your side as a small-town American from a blue-collar family who joined the U.S. military for a better life. In my years of service to you and your constituents, I have faithfully executed my duties as your scribe, giving voice to your vision through memos, tweets, and legislation. I am an ambassador to your constituents, representing your heart, mind, and values. Yet I recognize our time is one of deep division, discord, and discontent. And as a veteran, sworn, like you, to protect and defend the constitution, our moment is one of great pain.

I, like so many other veterans who came of age in the shadow of 9/11, found ourselves on the front lines of a series of endless wars against an invisible enemy. Wars that, by some estimates, have resulted in the cumulative deaths of over 4.5 million people while leaving over 7.6 million children suffering from acute malnutrition. The gods gave birth to a brave new world on that hapless day, where, in the minds of many, the abstract arrangement of vowels and consonants used to discern identity, paired with the perceived type and quantity of melanin in their skin, determined one’s right to life. Many of my brothers and sisters in arms grew numb to the plight of the desperate souls of the Middle East living under a perpetual hail of bullets and bombs. Yet, through it all, I maintained a belief that the ignorance of a few is not a reflection of the many, and though America, too, makes mistakes, its values of inclusivity, equality, and justice for all set us apart and give hope to millions of the oppressed that they too can realize a better life. That is why it pains me to watch as America, in this moment of opportunity to embrace its most foundational values, has turned its back on the most beleaguered population on earth and allowed daily tragedies, the depravity of which transcend the worst nightmares of Dante Alighieri.

It is undeniable that the gruesome deaths inflicted by Hamas are revolting, repugnant, and reprehensible, but have we not learned from our own misdeeds, miscalculations, and misadventures? What has America wrought in Iraq, Syria, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Somalia, and Yemen in response to the tragedy we suffered in lower Manhattan? Is the price of security payable only in the currency of the charred, lifeless bodies of the innocent? Could it not be procured through books, clothing, or food? With each scarring clip sliding beneath my thumb, I see young boys and girls named Ahmed, Mona, Hassan, and Nour suffering incomprehensible physical and emotional harm. I ask you, are their lives less valuable than those of Timothy, Jessica, Michael, or Karen? Is it not a matter of sheer luck that you and I were born with the privilege to determine the fate of others? Born with the privilege of never knowing the grim din of armed drones circling overhead like angels of death sent to reap human souls? Our unconditional support for Israel's endless bombardment will reverberate through history not as a demonstration of America's commitment to democratic values but yet another manifestation of its abuse of power in the name of short-term goals despite its long-term security interests.

We must not allow the crimes of previous generations to justify atrocities in ours. As the most significant economic and military power on earth, it is incumbent upon the U.S. to treat all nations and their actions equally under the law despite their race, religion, or creed, lest we, too, suffer the catastrophic fate of empires past. For if we cannot stand up against the indefensible, then our complicity will leave our constitution forever stained.

In this time, the Senate must act in accordance with its obligations to protect and defend the American people. Why, then, I ask, does our perceived obligation to protect and defend the Israeli people today take precedence over American security tomorrow? Each civilian killed by American guns, bullets, and bombs secures a generation of hate for our project of self-government and self-determination. Neglecting our obligations to international law ignores the security of our children and our children's children. The ramifications of which will cement our place in the annals of history as yet another empire that lost its way in the fog of war. Fredrick Douglas once opined, “Where justice is denied, where poverty is enforced, where ignorance prevails, and where any one class is made to feel that society is an organized conspiracy to oppress, rob and degrade them, neither persons nor property will be safe.”

Human Fever Chart

Whether damned with faint praise or hidden away like baby cine-monsters in the attic, early talkies go largely unloved nowadays.

Is it a function of “class” (every iteration implied), this ghetto we’ve made, this undeservedly obscure and cramped compartment of moviedom?

Yes, I’ll defend the jangled rhythms and febrile mood swings of America “on the bum” merchandized, albeit unconsciously most of the time, by ‘30s Hollywood.

And later brushed aside by even more insidious machinery…

Canonical thinkers apparently haven’t any room in their social imagination for squalling. The cheapest magazine story on celluloid may suddenly evoke its Depression-era audience (unwashed bodies, injured pride, volcanic anger and all).

Genuine cynicism, meanwhile, tends to leave nonplussed film buffs in the dust.

I’m thinking of that human fever chart, Joan Blondell, under whose enormous “lamps” the whole world stands judged in stark, crummy relief.

No wonder she remains elusive to rankings (domain of momma’s boys), and to an increasingly centralized taste. Better to keep that looming collapse, our Great Manic-Depression, at bay…

An avenging conscience no séance would summon lightly, Blondell flies high above the Cultured Class and its decorous, dizzy noodle.

Even on television, where the coyness of Professor Dimples (the late Robert Osborne) has introduced a whole new audience to pre-Code, his winks and qualifiers inevitably signal “guilty pleasures”.

All Talking Pictures continue to resist dilettantism, evoking the sonic presence of slum kids who bestowed Yiddish on James Cagney. And “that unmistakable touch of the gutter” for which he publicly thanked them…

Red Dust

The hooker with a heart of gold is among the most predictable and dishonest of Hollywood’s clichés. But the hooker with a sense of humor is another matter. As Vantine, the Saigon floozy stranded on a rubber plantation in the jungle, Jean Harlow is easy-going and generous, but also tough and astute, with an irrepressible wit that is by turns quirky and acerbic. She pines after the plantation owner, a sweaty and rough-hewn Clark Gable, but she never wilts, even after he dumps her for a prim, hypocritical married woman (Mary Astor). At loose ends, she passes the time bathing in a rain-barrel, cleaning the parrot’s cage (“What’ve you been eatin’, cement?”), hilariously debating the merits of rocquefort and gorgonzola, and puzzling over the story of Little Molly Cottontail while Gable’s hand goes hippity-hop, hippity-hop towards her leg.

Elektro

Drawing of a Photograph of a Robot, circa 1939

Elektro, the Westinghouse ‘Moto-Man,’ was constructed by the Westinghouse Electric Company, in Mansfield, Ohio, for the 1939 New York World’s Fair, where he and his robot dog Sparko entertained thousands. Elektro is made up of more than 900 handmade parts, including a 60 lb ‘brain,’ consisting of 48 electrical relays, that occupies approximately 4 cubic feet of space outside his body. He can walk, talk (he has a vocabulary of some 77 words) and count to ten on his fingers. Elektro can perform 26 separate movements, and can turn 45 degrees in either direction. In addition to being able to distinguish between the colors red and green, Elektro also smokes cigarettes and cigars, exhaling from both nostrils.

Portrait and mini-bio by Thomas Zummer