The Demiurge and the American Eyesore

It is the custom of illuminated manuscripts to transform sacred words into shimmering icons which break, easily, beyond the sensory limitations of simple text, rendering ordinary letters into evocative, animate visual form that invites the eye to idle awhile at the brink of transcendence, rather than stand at a distance, remote and unyielding, daring to be comprehended, accepted, believed. Strange and barely recognizable wildlife appears on vellum leaves, creatures that wind and unwind in ceaseless whirlpools of bejeweled abstraction. Or they are, if you prefer, the spirited exoskeletons of snakes, dragons, waterbirds — Celtic and Germanic obsessions meeting the Apostles of Christendom. Emerging in the British Isles between 500–900 C.E., The Lindisfarne Gospels provide an arena, lapidary and starlit, where paganism devours Christianity while also birthing the religion anew into what can only be described, if you're honest, as “motion pictures.”

Zis. Boom. Bah.

The tenth edition of Zis. Boom. Bah. is entitled …

Heroes for Sale

OPEN THIS POST TO LISTEN IN

https://archive.org/details/zbb10

*

Scene 1

Alex Bartha’s Hotel Traymore Orchestra - It Must Be Swell to Be Laying Out Dead

Chick Bullock & His Levee Loungers - Are You Making Any Money?

Freddy Martin & His Orchestra - Remember My Forgotten Man

Blue Steele & His Orchestra - There’s a Tear for Every Smile In Hollywood

*

Scene 2

Chahadé Effendi Saadé - Taqsim rast

Kanoni Artaki - Soultanigiah

Moustapha Bey Rida - Taxim hugaz kar wahda

Kementchedi Alecco - Kurduli hidjazkiar taxim

*

Scene 3

Victor Military Band - United Empire March

Imperial Marimba Band - General Pershing March

Charles Prince’s Band - Manhattan Beach March

Berg’s Concert Band - Marche Indienne

*

Scene 4

Henry Burr - America, Here’s My Boy!

Alfred Lester - A Conscientious Objector

Frederick Wheeler - Boys In Khaki, Boys In Blue

Morton Harvey - I Didn’t Raise My Boy to Be a Soldier

*

Scene 5

Irān-od-Dowleh Helen - “golriz (Shur)

Moluk Zarrābi - "darāmad, "zābol (Chahārgāh)

Abd-Ol-Hoseyn Shahnāzi - "mokhālef (Segāh)

Mortezā Ney-Dāvud - "bayāt Esfahān, Bayāt Rāje’ (Homāyun)

*

Scene 6

Ramona, with The Park Avenue Boys - We’re Out of the Red

Horace Heidt & His Orchestra - Dawn of a New Day

Victor Young & His Orchestra - The Grass Is Getting Greener

Paul Robeson - Spring Song

by RJ Lambert

The Age of Chiselry

Oh Talkies; you were so young and unapologetic. Your players weren’t necessarily pretty, but they had snappy comebacks and sassy retorts, haiku spit straight from America’s open sewers, tenements and speak-easies. Inhale that pure, sweet spleen of Edward G. Robinson (“Aah roll your hoop”) or William Gargan (“Ring off, dumb-bell”).

I imbibe the voice of James Cagney with twisted glee, as if I’m celebrating some perverse victory when he yells, “Down, bezark, down!” What is this gloomy zest for life, something ricocheting in the atmosphere, a hip jazz tempo — can we honestly call it escapism? We want to be able to go crazy, but with someone holding our hand.

Each hairy-knuckled Adam did his level-best to fast-talk us out of The Great Depression. Every hard-knocks Eve whispered New Deal Dada to quiet our jangled nerves and howling bellies. Up on the screen, no fantasy, ourselves, one choral personage laughing backwards in sync sound, unrepentant, unredeemed. Zasu Pitts, Evalyn Knapp, Glenda Farrell, Pert Kelton – strange and lovely names echo immortal in my ears, women who kissed “yeggs” and stayed out late with their “bindelestiff” pals.

Empty pockets? We called them “Hoover Dollars” or, drooping inside-out, “Hoover Flags,” banners of a bedraggled nation. Those who spoke Pig Latin (many were fluent then) said “oday” for the money nobody had, a.k.a. “mezuma,” “sugar,” “cush,” “potatoes.” The short, punchy use of words, poetry with grit – our Two-Fisted Humanism muscled its way into the Sound Era as movie palaces rumbled.

Big Boy

In the splendid menagerie of players, archetypes, stereotypes and shtars who toiled before the cameras at Warner Bros./First National in the first blush of economic depression, none is more difficult or wears less well with time than Al Jolson. He was a man of undeniable talent, yes; and a star of such immense proportion that his name – unlike that of say, George Arliss – is still somewhat known, even to this doggedly amnesiac society. Hopelessly addicted to the approval of an audience, any audience, it has long been said that he could be mesmerizing on stage (“To sit and feel the lift of Jolson’s personality,” gushed Robert Benchley in his review of the 1925 Broadway hit Big Boy, “is to know what the coiners of the word ‘personality’ meant. Unimpressive as the comparison may be to Mr. Jolson, we should say that John the Baptist was the last man to possess such a power.”), but within the more intimate confines of a 78rpm recording or, more to the point, a motion picture, Jolson could be downright monstrous: an insatiable, chronically insecure, burnt-cork gorgon; eyes aflame; barreling heedless through every note, every step, every gesture; as if he were the primal ooze of showmanship itself. And while each picture he made for Warners in that period falls hostage in varying degrees to the man’s over-amplified brio, 1930’s Big Boy, adapted from the aforementioned stage success, carries the added burden of having Al Jolson, for almost the entirety of its 68 minute running time, playing the role of a stableboy in purebred, mainstream American blackface. You can forget about the plot – a textbook set of Musical Comedy contrivances involving crooked gamblers, a faithful servant, Reconstruction-era flashbacks and the honor of the Kentucky Derby – or even the film’s merits (of which there are unsurprisingly few), Jolson’s extended appearance ‘neath the burnt cork of Antebellum-era modernity has delivered this film to what small notoriety it enjoys (if that’s the word for it) to this day. Whatever it may have been then, it stands now as a cultural curio; the kind of film latter-day viewers, pretending to a sophistication as moored to reality as the trappings of minstrelsy, dismiss with a chuckle, maybe a shudder, maybe a stock banality or two on the less-evolved attitudes of the period it reflects (as if ours were an arcadia of human tolerance). It’s too debased to be classified as maudit; and it barely breathes in the 21st century consciousness.

by Tom Sutpen

The Sound of Fury

“America, as a social and political organization, is committed to a cheerful view of life,” Robert Warshow wrote in his seminal 1948 essay “The Gangster as Tragic Hero.” Democracies depend on the conviction that they are making life better and happier for their citizens; only feudal and monarchical societies can enjoy the luxury of fatalism or a fundamentally pessimistic view of life. Praising the gangster genre as a form of modern tragedy, Warshow also accounts for film noir in his statement that, “There always exists a current of opposition, seeking to express by whatever means are available to it that sense of desperation and inevitable failure which optimism itself helps to create.” The gangster’s demise is the purest American tragedy because it is driven by his mania to climb the ladder of success. The end of his saga is inevitable, so in chasing success he is really chasing failure; his self-destructiveness expresses defiance at the inevitability of defeat, but also confirms it.

The Inescapable (and Invisible) Whit Bissell

To the casual viewer, it might seem like character actors like William Demarest and Elisha Cook, Jr. appeared in every film ever made. And there’s no denying that in certain genres and during specific periods, they were ubiquitous. But the actors’ filmographies can’t touch that of the great Whit Bissell in terms of sheer volume. They may be better known, but the numbers go to Whit.

Nemesis Never Misses

“Sure, I was in the hospital, but I didn’t go crazy. I kept myself sane. You know how? I kept saying to myself: Joe, you’re the only one alive that knows what he did. You’re the one that’s got to find him, Joe. I kept remembering. I kept thinking back to that prison camp. One of them lasted to the morning. By then, you couldn’t tell his voice belonged to a man. He sounded like a dog that got hit by a truck and left him in the street.”

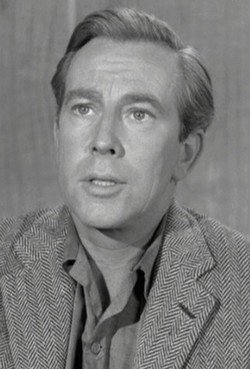

In Act of Violence, Robert Ryan is the Terminator – he travels to LA from far off, gets your address in the phone book, and comes after you to kill you. He will not stop. Dragging one dead leg behind him, wearing his New York clothes, raincoat and fedora, in the LA heat, a sheen of perspiration glazing his features. You go fishing and he rows after you, one oar squeaking like his stiff leg. He hides his boat in the shade of a rocky crag sculpted by God when drunk as an abstract Robert Ryan portrait (all the rockpiles of the Earth are drunken Robert Ryan likenesses), he even comes to your house. He sees your pretty wife and your baby and they inspire nothing but envy and the desire to kill.

Van Heflin, amphibious face with bulging brow, boiled egg eyes, mouth a remorseful stoma, is the Everyman, the quarry. He’s a good guy, a family man, runs a business, pillar of the dreamy small-town community, only he did something bad back in the war. Is Robert Ryan his conscience? Yes, a six-foot-four Jiminy Cricket with a handgun, coming to settle a debt.

Fred Zinnemann only made this one film noir, an unlikely genre at MGM, especially with a story that flips the lid off respectable family life and finds seething corruption in the all-American householder’s soul. Robert Surtees lights it for the highlights in Janet Leigh’s wide eyes, and the creeping darkness. Even the family home has perpetual window-frame cruciform shadows quartering up every room. Robert Ryan in the bright sunlight is even scarier because he simply has no business being there.

The Lesser Evil?

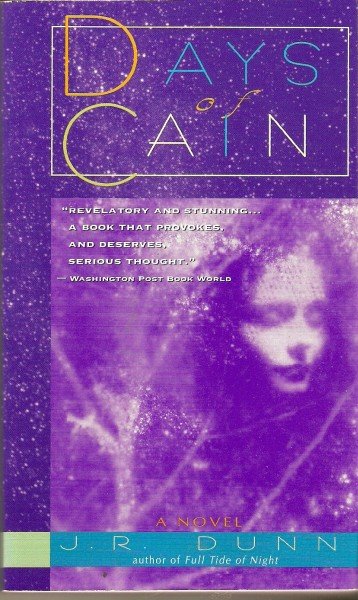

A novel about time travel and the Holocaust? How do you pull that off?

In the case of Days of Cain (probably the only such case), superbly.

The author, J.R. Dunn, has, to my knowledge, written only two other SF novels. I’ve read This Side of Judgment, which is good enough but nothing to get wildly excited about. I got wildly enough excited by Days of Cain, long out of print (released by Avon in 1997), that I scoured the Internet and bought 14 copies which I distributed to everyone I could think of who might be interested.

As I have to admit, many of them (including a published SF author) never responded with massive enthusiasm. Yet this doesn’t faze my own enthusiasm a bit. Both my wife (one of the most serenely intelligent beings on earth) and I felt we had wended our way through one of the finest explications of time travel written and one of the most telling and devastating unveilings of the Holocaust—one that puts Sophie’s Choice to shame.

Success is a Racket

The room is windowless and bare except for a table under a low-hanging lamp with a naked bulb. It’s the kind of room where only bad things can happen. A pack of tough cops gathers around the table, encircling a hapless innocent whom they plan to frame for a murder. One cop reaches up and shoves the hanging lamp so it swings back and forth, round and round, making shadows of men lunge and shudder on the walls and hot light pulse on the pale, nervous forehead of the victim. No one speaks.

Karl Freund, already the cinematographer of Metropolis and The Last Laugh, may not have invented the swinging lamp effect here, in the pre-Code Afraid to Talk (1932), but he exhibits near-total mastery of noir lighting almost a decade before the noir cycle would begin. (Swinging lamps would reappear in Crossfire, Desperate and other films, always evoking the menace of imminent violence.) This relentless drama of civic corruption—which can hardly be called an exposé, since it assumes a general knowledge that everyone in power is a crook—deserves the label of proto-noir, though it also illustrates the gaps between pre-Code and noir.

Afraid to Talk is almost gleeful in its boundless cynicism, almost sadistic in the way it dwells on men of power smirking and chortling as they torment their powerless pawns. The bad sleep well, and they have a lot of fun, too. There are few scenes in either pre-Code or noir as shocking as the one in which boyish Eric Linden—one of the “Gee, that’s swell” brand of male ingenues—is beaten to a pulp until he finally offers a false confession. The beating takes place off screen: we hear it while watching a couple of men taking a break from pounding the kid (they turn out not to be real cops, but hired thugs of the District Attorney) washing their hands, Pilate-like, and complaining that their coffee is cold. Afterward, we hear that the victim is spitting blood, has internal injuries, and was beaten on the soles of his feet. (Not too smart, since the D.A. tries to claim he was injured resisting arrest!) When one of the more squeamish thugs expresses discomfort at what they’ve done, the others sneer at him: “Are you turning pansy on us?” and dismiss his guilt with a shrugging, “It’s all in the game.”

Linden is Eddie Martin, a bellboy who had the bad luck to be in the room when a racketeer was bumped off, and the worse luck to be a convenient fall guy when the corrupt party bosses need to convict someone, but can’t touch the real culprit because he’s blackmailing them with evidence of their colossal malfeasance. While Eddie’s fate is cruel, the film is anything but glum. It’s full of wild parties, drunken women in evening gowns dancing on table tops, and fractured, swirling montages of speakeasy life. The big boss of the party doesn’t just have a bar behind a swiveling bookcase—when he pushes a button, a panel slides out of the wall and there’s a bartender standing behind it, already shaking a cocktail. (Does the man live in this cubbyhole? Anything for a job, presumably.) And in the film’s most memorable image, racketeer Jig Skelli (Edward Arnold), celebrating his release from jail at a party in a private room, draws aside the deco-patterned curtains of a picture window to reveal the floor of a nightclub, where a line of chorus girls enters dressed as chain gang prisoners, a delirious conflation of two of the Depression’s iconic images. I Am a Fugitive from a Floor Show.

Ballyhooing John Strausbaugh

Award-winning history writer John Strausbaugh tells fascinating stories about the past, bringing fresh perspectives to events and characters great and small. Open this post for links.

Skyscraper Souls

The Grand Hotel formula is stripped of romance and transported to an imaginary skyscraper that towers above the Empire State Building. Warren William is the building’s visionary developer, David Dwight, whose ego stands even taller than the monument he has built to himself, and whose charm is dangerously hard to distinguish from his amorality. His colossal achievement, an art deco Tower of Babel, justifies betrayals and cruelty. After pulling a double cross by manipulating the stock market, he points out to his outraged associates that if they were benefiting from his chicanery instead of losing their shirts, they would call him a financial genius.

His machinations cause a stock bubble that wipes out nearly all the other characters, a miniature parable of the Crash that leads to robbery and death, disillusionment and self-discovery. The skyscraper’s souls include an innocent small-town girl (Maureen O’Sullivan), an obstreperously eager young go-getter (future director Norman Foster), a prostitute, a jewelry-store owner, a radio announcer , an unfaithful wife, and Dwight’s intelligent, loyal secretary and mistress, who is no longer youthful enough to hold his interest.

Name That Anarchist

Giuseppe Zangara was a short, sickly, poor immigrant who saw capitalists as the root cause of his troubles. In 1933, when newly-elected president Franklin Roosevelt stopped to give an impromptu speech from the back of his open-topped car, Zangara decided to take care of that part of his problem. Short as he was, he had to stand on a chair to get a clear shot, which made him easy to spot and grab. He still fired five times, missing the President, but hitting four others, killing Chicago Mayor Cermak. He was sent to the electric chair, hating capitalists to the very end.

by Jim Knipfel