Curtis Harrington Eulogized by Barbara Steele

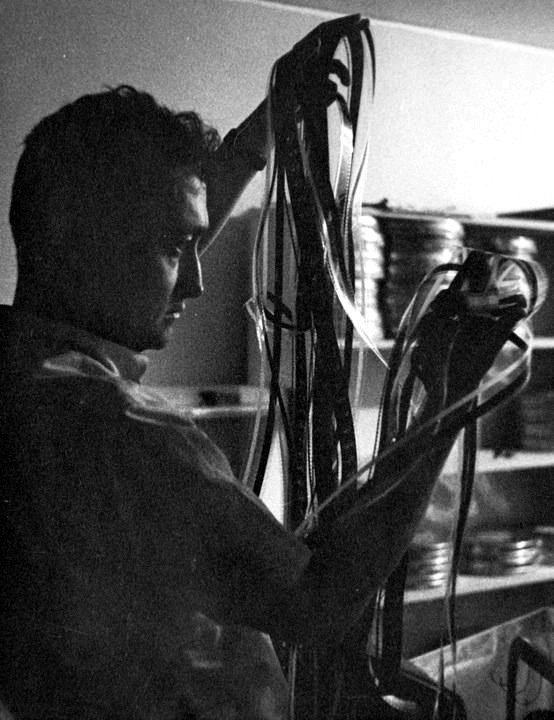

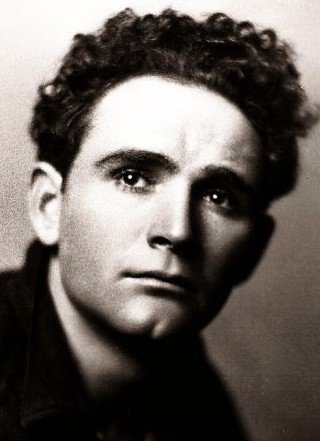

Director Curtis Harrington (1926-2007) lead a fascinating life. Barbara Steele delivered this eulogy at Harrington’s funeral – and The Chiseler thanks her for providing an intimate portrait, published here for the first time. Today would have been Harrington’s ninety-first birthday.

Good evening. Although Curtis was born in Los Angeles, to me he had the grace, mannerisms and soul of a Southern gentleman, right down to his white linen suits, wicked, playful and baroque, a fabulous gossip and fabulously informed. He stood in the center of his own drama, in fact when I think of Curtis I always think of him as an opera. Wasn’t the obituary photograph of Curtis in the L.A. Times where he stood with a stone cherub just perfect, maybe a slightly wicked one with that wonderful ironic smile? The Los Angeles that he inhabited was the city of his childhood – the Orpheum Theater, the Angel’s Flight, the red cars, C.C. Brown’s ice cream parlor, he mourned whenever one of his childhood haunts closed down. He was the last of an era of great raconteurs, like Gavin Lambert, Ivan Moffet, John Schlesinger and others. He had the great gift of friendship, witness everybody here tonight; I met everybody in that marvelous house of his that seemed to have been transported from a Tennessee Williams dream. The fountains, the fish, the flowers, the books, the art deco pieces that he so treasured, Judy Garland’s slippers, the fat fabulous cats that would come and go, the mummified bats in their silver cases in his bedroom and the Poe etchings. The extraordinary array of guests. Where did they all come from?… I met everybody there that I wanted to meet: Marlene Dietrich, Gore Vidal, Russian alchemists, holistic healers from Normandy, witches from Wales, mimes from Paris, directors from everywhere, writers from everywhere and beautiful men from everywhere. I was never quite sure if he was the host or the waiter because he would disappear into the kitchen in his tuxedo for an eternity while we the guests would hear the endless grinding and blending of machines where he was invariably whipping up mountains of whipped cream. I was invited to one party where we were asked to wear formal gowns, it was 100 degrees in August with no air conditioning for a dinner that went on for six hours where we were all photographed for House and Garden. Sweaty guests.

A lover of big cities, the city he loved most was Paris. He lived there in 1953 and quickly learned the language, he was a regular at the Cinémathèque Française where he befriended Henri Langlois. He would make frequent pilgrimages to the Père Lachaise Cemetery and as a matter of principle he would go and see every French film in Los Angeles. but above all Curtis had the remarkable gift for friendship. In some ways he could be a snob, but it was never based on money, title, social rank or privilege, it was a snobbery of the heart and of the mind. He responded to talent, to beauty, to charm and to intellect, he was forgiving of human foible and social flight but once Curtis had decided that he liked you, he admitted you into his charmed circle, once you were inside it, you would never be banished, it was such a delightful place to be, you wouldn’t want to escape… and you loved him with all your heart.

by Barbara Steele

TIEF OBEN: A True Halloween Story

I was filming in Austria on Halloween night in the ancient mining town of Eisenstadt, the film TIEF OBEN. We had great steaming wooden vats of hot red wine for everybody to keep them going. It was arctic weather, snowing fiercely when the director suddenly asked all the extras to be naked other than their boots and the little mining lamps on their heads. Naturally they refused. At which point the director tore off his own clothes in a rage as a challenge…and was the lone white freezing body in the dark night.

In the middle of this frenzied rebellion, I decided to walk home alone. The local villagers had made little paper boats that they sent down the river set alight, a ritual of remembrance for their dead relatives…

Suddenly a dozen motorbikes came roaring by with everyone on them dressed as skeletons. They got off their bikes and started to dance around me in a circle holding hands – then they mounted their motorized steeds and took off into the night making unearthly shrieks and whistles….

Warner Writers Back

Erwin Kelsey rejoined the Warner writing staff yesterday, starting on new term contract with the company. His first assignment will be “Silver Dollar.” Houston Branch is also back at Warners, and Wilson Mizner is slated to go back today.

The Hollywood Reporter: Friday, July 8, 1932

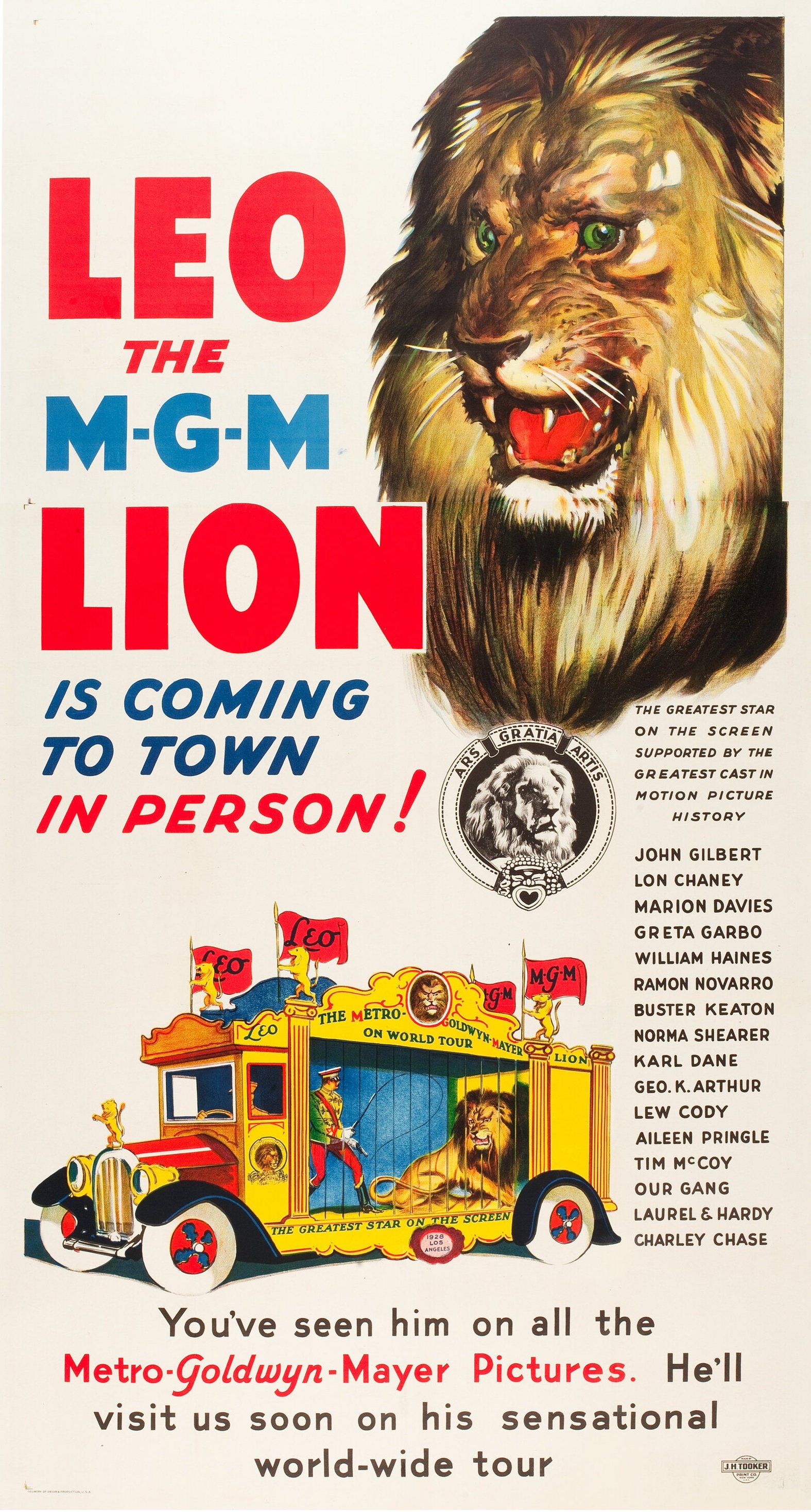

Ars Gratia Artis

Film, as they say, is an industry; and like all industries, it feels that it must side with Israel's genocide in Gaza. Has any hub of this larger Industrial Majesty — whether Cineaste, Criterion, MUBI or Sight & Sound — called for a ceasefire? They each responded to middle-class progressivism by reshuffling their respective canons for Inclusivity's sake, without disturbing the bottom line of billionaires, but internalizing the Holocaust’s ethical lessons — well, that would be expecting too much from movie fetishists weeping over Night and Fog. Naturally, they remain dry-eyed and decorous as the Holy Land starves the children of Palestine.

Cinephiles may as well be the IDF bullets fired at UNICEF.

Their institutions have reduced Palestinians to nothing.

by Daniel Riccuito

Killing Humanitarian Workers as a Strategy: Israel’s Endgame in Gaza

Israel described its clearly deliberate killing of seven humanitarian aid workers on April 1 as a “grave mistake”, a “tragic event” that “happens in war”.

Israel is, obviously, lying. This entire so-called war - actually genocide - in Gaza, has been based on a series of lies, some of which Israel continues to peddle.

For some, in the mainstream media, it took months to accept the obvious fact that Israel has been lying about the events that led to the war and the military objectives of its constant targeting of hospitals, schools, shelters and other civilian facilities.

So, it was only logical for Israel to lie about killing the six internationals, and their Palestinian driver, of the World Central Kitchen (WCK). Notwithstanding an event as atrocious as this, it is implausible for Israel to start telling the truth now.

Luckily, few seem to believe Israel’s version regarding WCK, or its continued massacres elsewhere in Gaza. Israel “cannot credibly investigate its own failure in Gaza,” the US-based NGO said in a statement on April 5.

Hate Poetry: Film Noir’s Final Form

It is the epitome of John Alton's vision of the night. A darkness at once creamy and sour, suffused with smoke, misery, and the jawlines of strange looking character actors.

Alton seems to operate from a principle of pitch darkness, interrupting its velvet flow with the bare minimum of lamps and lightbulbs, creating little pools of illumination amid the pervasive dark that forever seem on the verge of being swallowed up by the great inky amoeba they nestle in.

Is cinematography the sum and substance of Noir — Noir itself — or does baseline hostility to American optimism define a genre benchmark, 1955’s The Big Combo?

Richard Conte’s “Mr. Brown” may spit out his cold Noir sermon — “First is first and second is nobody” — faster than James Cagney, his spiritual forebear in the 1931 pre-Code classic, Blonde Crazy: “The age of chivalry is past — this, honey, is the Age of Chiselry.”

Noir was never fundamentally a genre of shadows, but rather defined itself as a set of underlying attitudes and assumptions — All Talking Pictures were poised, Johnny-on-the-spot, to capture the ensuing madness when the stockmarket crashed in 1929.

It’s tempting to posit this moment of serendipity as both Noir’s metaphysical and political birth, and to suggest that economic calamity and advancing technology met for preordained reasons.

But what sinister apostate canon could possibly have contrived a history of cinema to beat the band where raw indifference is concerned — to produce a Robert Mitchum, whose physical beauty is an effortless nihilist shrug?

Ed Wood Post-Plan 9

Given the number of myths, legends and simple misinformation that’s been spread about Edward D. Wood, Jr. in everything from Michael Medved’s muttonheaded book The Golden Turkey Awards to Tim Burton’s well-meaning fairy tale of a biopic Ed Wood, it seems people have an awful lot to say concerning a man about whom they know very little.. People who have seen at most one or two of his films know the party line, though, and are happy to repeat it ad nauseum. Ed Wood was the worst director who ever lived, and his 1959 sci fi horror conspiracy film Plan 9 from OUter Space the most incompetent movie ever made. Even if they haven’t seen the whole film, even if they couldn’t tell you what the storyline is (yes, there’s a clear story), they can tell you all the reasons why it’s bad. It doesn’t matter that most of the things they list are incorrect—they’ve read them online and heard them from their smug friends, so they must all be in there someplace. For most, it’s all they know and all they need to know. It seems Plan 9 is the end of the story. Maybe after that no one let him make another movie, or maybe he died or something.

But Plan 9 was only Wood’s fourth film. He continued working regularly for almost 20 years after that, right up to his death in 1978. He would direct five more features (only two of which are considered “legitimate”) and write the screenplays for almost two dozen films directed by others.

Sylvia Sidney: Jailhouse Blues

“She always looked like she was gonna cry!” my grandmother would exclaim whenever Sylvia Sidney came up. In her 1930s heyday, Sidney was constantly cast as the victim of circumstance, hovering at the very bottom of the economic ladder, mixed up in crime and usually winding up in or near jail. “I was paid by the tear,” Sidney joked later, and that knowing comment is a measure of just how different she was from her on-screen persona. “My mother and I adored her and her films,” said Tennessee Williams. “She was always so fragile and plaintive. She appeared to need protection. Let me tell you: Sylvia needs no protection. She may look frail, but look in that exquisite purse she carries with her: it contains the balls of thousands of men who annoyed her; the hearts of those who crossed her; and the locations of those who betrayed her.”

Brown Furniture: Notes on Gaza from a Diaspora Cousin

My mother died recently, so I’m still in her home taking care of details. I’m also developing an increasing dedication to several pieces of her furniture: a tall cabinet, the dinner table, and a credenza where we stack the plates. Or maybe I should say, harboring an indecision. These three are a matched set in maybe cherry wood, I’m not sure. I think of them as friends but also wonder if the impulse is too dutiful. Rather than find my own décor, my own life, I’m going to set up a shrine to my parents and just be the secretary of their museum?

What dawns on me later is how fortunate I am: I get to have a full stomach and contemplate furniture, family, and the passage of time from the sprawling comfort of a large gray velour sofa. It’s a luxury to grant the dining table and credenza special powers, making them almost human, bestowing upon them character arcs and stories, practically giving them birth certificates. It’s a way to keep my mother present. And it’s ironic, too. Because the exact opposite is happening to an entire civilian population in Gaza. These past five months, the average Gazan’s personhood has been reduced to furniture.

I have a lot of relatives in Gaza. Some of my cousins are still there. Other cousins, evacuated to Cairo, watched their homes get bombed on television. There’s always been family in Cairo, it’s where my father was born. One of his sisters was a doctor. She married a Palestinian, also a doctor, and they worked in Gaza City, had children and grandchildren, were esteemed for their professional accomplishments. My dad, aunt, and uncle are long gone and I’m relieved they don’t have to witness what is happening, because witnessing is all I can do, and it’s overwhelming.

Doctors’ Wives

In the universe of Frank Borzage’s Doctors’ Wives (Fox Film Corp; 1931), women of a somewhat elevated social status can be cunning, downright predatory. They’re always on the prowl; particularly when it comes to their doctors. Warner Baxter plays Dr. Judson Penning: a big-time, big city surgeon; an aristocrat with a prescription pad, moving shark-like from patient to patient; half his life fearlessly staring into ungodly pits of human matter plopped onto an operating table, the other half at his practice, chained to the fin de siècle ennui and simmering hypochondria of rich, overdressed society dames, with only momentary deference paid to his luckless and long suffering wife (Joan Bennett). Adapted in tear-streaks by Maurine Watkins from a novel by Henry and Sylvia Lieferant, Doctors’ Wives might have yielded, with that premise, a respectable crop of marginally low-down smut had it been made at, say, Warner Bros. with Michael Curtiz or Roy Del Ruth directing – they at least seemed to know what to do with a hopeless assignment when they caught one. Instead it received a painfully earnest recitation at the hands of a time-serving, paradigmatic auteur – an otherwise true and singular voice within the commercial epicenter of this country’s film industry – one that, rather than transcending the handicaps built into the piece, only served to expose the plodding hollowness of its five-and-dime sophistication, replete with a Happy Ending plastered on so blatantly that one might be excused a longing for the gaucheries of simple contrivance. Doctors’ Wives, despite Borzage’s oddly negligible presence behind the camera, is no more than a glorified Programmer; a film that no one ever talks about; that no one with the exception of its initial reviewers has ever really written about. And while it may perhaps be too harsh a sentence to pass on a work so ultimately slight, one cannot escape the judgment that Borzage’s film achieves that most woeful condition an entry in the American canon can fall prey to: It’s the kind of movie that only a hopeless, hero-worshipping auteurist could love … or, conceivably, like.

by Tom Sutpen

The Great Sedition Trial of 1944

In a fireside chat in May 1940, Franklin Roosevelt, who was something of a conspiracy theorist, warned Americans, “Today’s threat to our national security is not a matter of military weapons alone. We know of new methods of attack – the Trojan Horse, the Fifth Column that betrays a nation unprepared for treachery. Spies, saboteurs and traitors are the actors in this new strategy. With all of these we must and will deal vigorously.”

A month later, he signed the Alien Registration Act, aka the Smith Act. It made it a crime punishable by up to 20 years imprisonment to advocate the overthrow of the federal or local governments. It allowed law enforcement to round up not just individuals but whole groups suspected of spreading sedition. To help agents track these pernicious activities and influences, it also required all foreign nationals above the age of 14 to register with the government and be fingerprinted.

As soon as he declared war in December 1941, Roosevelt directed his Attorney General to use the Smith Act to begin rounding up and putting away some of the country’s more vocal and visible Nazi sympathizers. In July 1942 a grand jury in Washington brought indictments against 28 people around the country, all of them irritants to FDR but few of them seeming to pose any real threat to national security. Among them were the German American writer George Sylvester Viereck, who had just been jailed in a separate trial for colluding with the Nazis, and William Griffin, the publisher of the New York Enquirer, accused of colluding with Viereck.

Viereck’s name has been lost to history now, but 100-odd years ago he was the darling of the New York literary set. He was born in Munich in 1884. His father Louis was the illegitimate son of a beautiful actress in Berlin and a royal lover, rumored to be Kaiser Wilhelm himself. Sylvester (he spurned the pedestrian-sounding George) was nicknamed Putty, for Lilliput, because he was so petite.

Five Star Final

No music, just the cries of newsboys. Mervyn LeRoy’s 1931 newspaper melodrama, Five Star Final, begins unconventionally. It’s a Warner Brothers social conscience film, but the grim social commentary is shockingly combined with pre-code spice and wit, as if I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang (1932) and Blessed Event (1932) got fused together in an explosion.

LeRoy directed seven films in 1931, most of them raucous comedies. Here he squeezes every laugh he can from the material, and every tear from the audience – it could get ugly, but somehow doesn’t, except when it wants to.

After the credits we get a classic 30s montage to introduce muckraking New York tabloid The Gazette, featuring a panoply of peroxide switchboard operators, probably all producers’ girlfriends – the star girl, Polly Walters, gets a shot filmed from the switchboard’s viewpoint, nesting amid her wires like a bleached spider.