Dr. Uranian

In 1959, in the basement of a tenement on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, Richard and Dorothea Tyler founded an avant-garde artists’ collective and funeral society called the Uranian Phalanstery and First New York Gnostic Lyceum Temple. The Tylers were influential underground figures in postwar New York City culture. They connected people and created webs of creativity and spirituality that blended music, visual arts, publishing, tattooing, Eastern religion, Gnosticism, Judaism, and communalism. And more. And all at once.

R. O. Tyler, as he was known, was big, bearded, heavily tattooed decades before it was hip, a jolly drinker and pot smoker who could talk your ears off. He was widely read and erudite, conversant in unusual and esoteric paths of human endeavor. For example, “phalanstery.” A very obscure word that goes back to the communes of the early 1800s and combines “phalanx” and “monastery." That Tyler knew and revived the term in the twentieth century says something about his knowledge of arcane history. That he wedded it to “Uranian,” an astrological reference to Uranus’s powerful influence on creativity and innovation, and to Gnosticism, and the Greek Lyceum, in a Jewish temple, suggests a wildly eclectic and synthesizing imagination.

He was born Richard Oviet Tyler in Lansing, Michigan, in 1924. His mother was a member of the I AM movement, a successor to Theosophy and precursor of the New Age era, founded in Chicago in the 1930s. His father was a working-class Great War veteran. Tyler fought in the Pacific in World War II, and was among the American troops occupying Japan afterward. He developed a deep interest in Japanese tattoo traditions and Asian mysticism. Returning to the US, he used the GI Bill to study at the Chicago Institute of Art, where he met not only Dorothea but also Claes Oldenburg.

In the late 1950s Richard and Dorothea moved to a basement on East Fourth Street between Avenues C and D, a very poor and ragged neighborhood in those days. When Oldenburg showed up, the Tylers got him his apartment. They not only continued their friendship, but it’s likely that Richard influenced Oldenburg’s famous sculptures. Tyler’s home was filled with toy guns and ray guns and plastic hamburgers. Oldenburg's soft hamburgers, cheeseburgers, and ray guns may well have been inspired by his friend’s plastic ones. Dorothea helped stitch them.

Tyler was the super of his building and the one next door, a yeshiva. When the rabbi there died he left the building to Richard and Dorothea, with the understanding that they would maintain its tradition as some sort of religious or spiritual place. Which they did, in their own way, by making it the headquarters of the Uranian Phalanstery and First New York Gnostic Lyceum Temple. Tyler named himself Dr. Uranian. The Phalanstery mixed paganism and Christianity and Buddhism and astrology and Jungianism and various other religious and philosophical modes into elaborate rituals and observances. Members took LSD and other psychedelics at some events. As for the Phalanstery’s role as a funeral society, when a member died, Tyler would conduct the forty-nine days of the Bardo ceremony to help the soul reach reincarnation.

Tyler was, among many other things, a jazz drummer and avant-garde musicologist, and ecstatic evenings of communally improvised music were central to the Phalanstery’s observances. The composer Keith Patchel likened Tyler’s musical theories, which involved astrology and numerology, to John Cage’s. Bill Heine, another artist who was also a magician and a jazz drummer (he played with Charlie Parker), remembered that Tyler had musical instruments all over the place. “As many as thirty or more of us came over and Richard would record us playing the instruments—often people would play an instrument that they had never played before—and it sounded amazing."

Tyler’s tattoo art was decades ahead of the curve. He was influenced by yakuza tattoos and other Pacific and African traditions well before the era of Modern Primitives and tribal tats. At a time when much tattoo design came from commercial "flash,” he was personally designing tattoos to fit the tattooee. As in most everything he did, he added layers of the mystical and magical. Jungian archetypes and astrological signs played roles in the choice of designs and symbols. Most remarkably, he acquired esoteric compounds from the Dalai Lama’s apothecary, substances like crushed pearls that had mystical and medicinal uses in Tibetan practice, and mixed them with his tattoo ink.

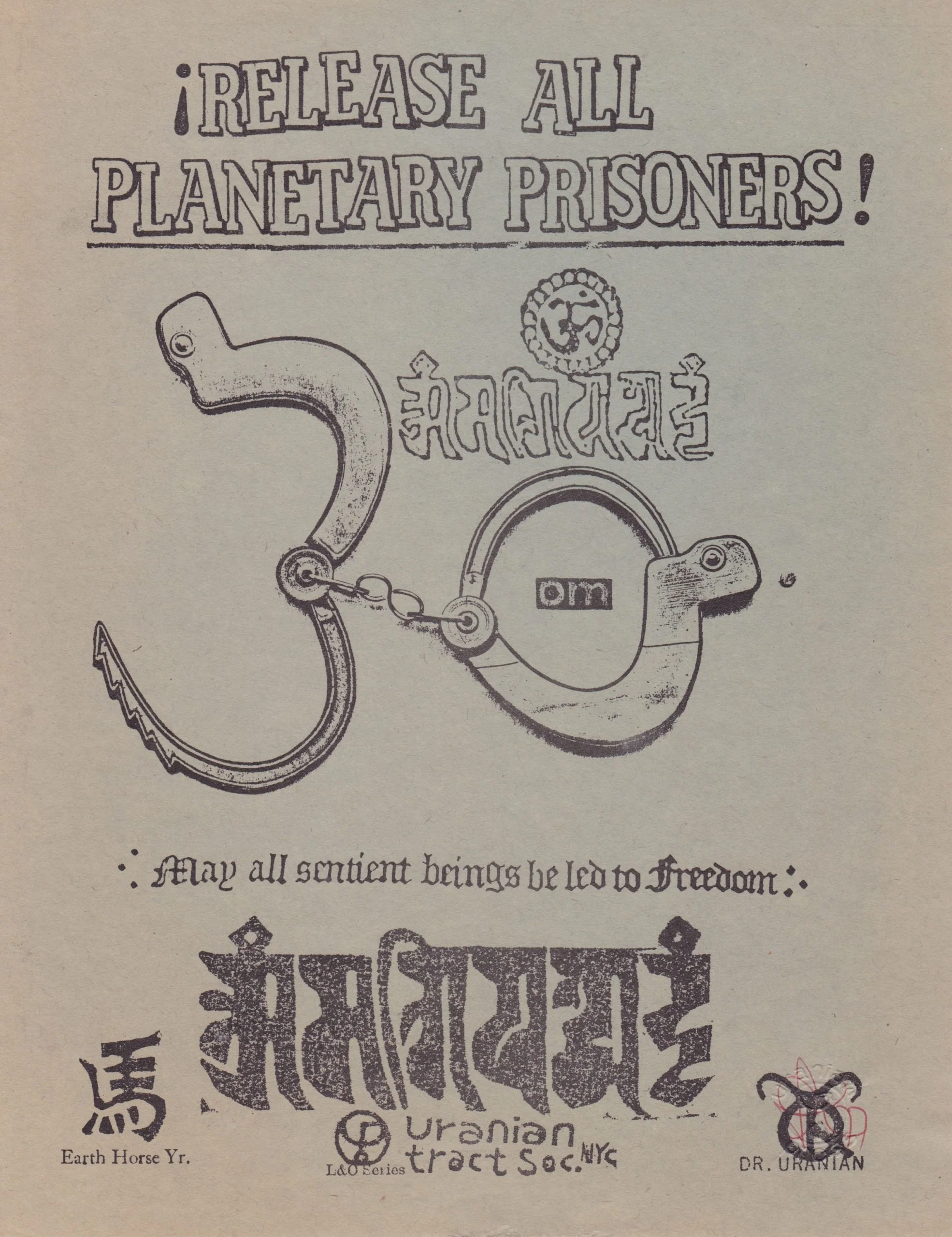

Under the rubric of his Uranian Press, Tyler also wrote, illustrated, printed, and distributed a stream of pamphlets, booklets, broadsheets, astrological calendars, Xeroxed collages, and lithographs. He sold them from a pushcart. Densely packing hand-lettered words and woodcut images, they’re mysterious, mystical, profane and comical, all at once.

Richard Tyler died of cancer in 1983. Dorothea passed away in 2012. Besides Oldenburg, it’s been said that Timothy Leary was influenced by Tyler’s knowledge of Eastern esoterica, and Ornette Coleman by his musical theories. Still, the Tylers remain obscure figures in standard art histories. Maybe someday the art world will assign them a more visible place in the history of downtown Manhattan culture in the decades after World War II, when New York City was, for a time, the art capital of the world, and the Lower East Side one of its busier quarters.

by John Strausbaugh