Nightmare Alley

If Mynona hadn’t existed, somebody would have had to invent him. And they did.

For more than 2,000 years leading up to Mynona (AKA Salomo Friedlaender, 1871-1946), since Moses and his tablets broke the bond between God (or the gods) and the world, leaving us only the Word, Western thought was on a collision course with…itself. Immanuel Kant’s philosophy, carefully studied by Mynona, was the ultimate attempt at damage control. He presented an intellectual system that accepted the mind’s divorce from phenomena (nature, to put it less technically) even as it built bridges among other minds via universal a priori concepts. Among them were certain capacities of the imagination. Indeed imagination was the only thing that could rescue objective reality from the status of an illusion. The independent truth of the world couldn’t be proven, but it could be intuited and expressed. By the end of the Eighteenth Century, poets and artists, as ministers of intuition and expression, had glorious and heroic work to do, and they took it on with gusto. For them, exploring the contours of feeling and translating their discoveries into language was like coming to a vast banquet.

But they discovered, again and again, they had bitten off more than they could chew.

By the time Mynona got to the table, the food was fairly picked over yet edible, even exotic, but heartburn was on the way. Described as a philosopher by day and a literary absurdist by night, the prolific, self-invented Mynona, which is a reversal of anonym, produced a handful of serious philosophical works (as Friedlaender) and a ream of so-called grotesques (under his pen name). These were fantastic or ludicrous stories, of which the novella “The Creator” is probably the most prominent. Prominent is an overstatement because the volume of the same title, published by the Wakefield Press, is the only collection of the author’s writing available in English. It contains just two items, the novella and one of the grotesques, “The Wearisome Wedding Night.” In spite of the waves of translation from German, in the 1920s, 50s, 70s, and 2000s, only a handful of his stories had previously appeared, in a few anthologies.

With their debt to Poe and E. T. A. Hoffman, the stories are certainly weird enough and sufficiently overwrought. At least the Dadaists and Surrealists who praised them thought so. But by the time Mynona wrote “The Creator” in 1920, the great age of poetic enfranchisement was past. Schiller’s, and Goethe’s confidence in the poet’s capacity to unite inner and outer reality, and even Hölderlin’s desperate reach for transcendent realms had left in their wake the goblins of the unconscious and the stark imperative of the will. This was the Janus face of the modern imagination. Mynona literalized the relation.

The narrator and “hero” of “The Creator,” Gumprecht Weiss, has, as with any good poet, an aptitude for dreaming. But he gradually finds that his dreams, especially of a mysterious and desirable woman, seem to have the power to manifest themselves in reality. Or is it that Elvira, the woman, is also dreaming him? Finally meeting face to face, they come under the influence and tutelage of Elvira’s guardian, the Baron. A sort of scientist of the paranormal, the Baron sees the couple as subjects apt for working on, especially to demonstrate his theory (and Salomo Friedlaender’s) that the mind can not only alter reality but shape it to the ultimate degree. Weiss is already on that page:

My imagination is an entire world that is all mine. …the whole world blossoms from the imagination as the tree sprouts and blossoms from a seed. If you succeed in tracing the world around you, a world that appears to be so stubbornly independent of human will, back to its internal germinal state, you will gain a powerful hold over your fate, which in its primordial form is, after all, nothing but a function of your will, your freedom.

One is tempted to recall Samuel Johnson’s response to Bishop Berkeley’s theory of idealism: “I refute it thus!” he said and kicked a stone lying in the road. Reality tends to leave things lying around that can get in the way of all that Nietzschean imaginative will. In any case, the Baron has an answer. With a machine of his own invention, which he calls a television (!), and a series of unusual mirrors, he shows the two not-yet-lovers how they can focus their minds to create a united being before their bodies ever truly physically engage. Something similar happens in the grotesque “The Wearisome Wedding Night.” Such a high bar for hooking up would seem to foster an unprecedented level of performance anxiety among newlyweds.

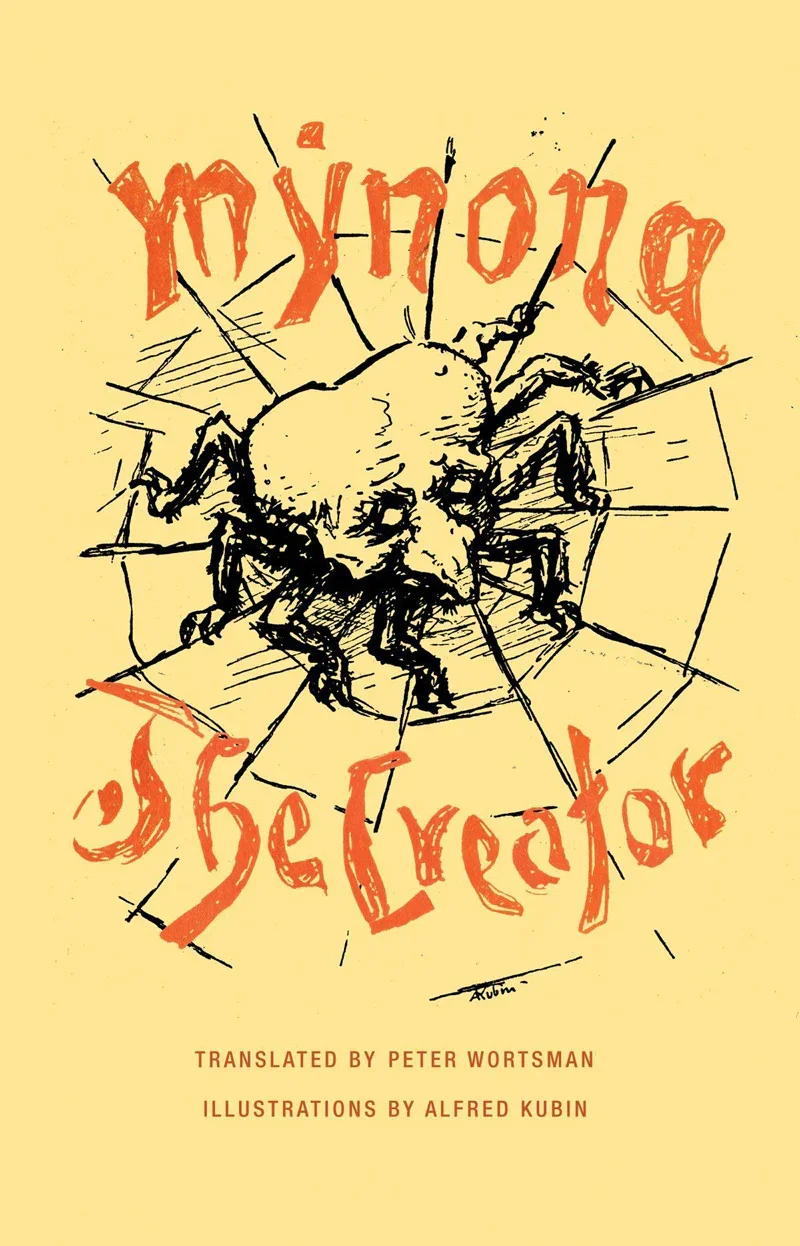

If all of this sounds remotely credible and not like metaphysical hoo-hah, it is worth asking how much Expressionist, Surrealist or Symbolist writing you have read and whether you have attempted to navigate the forest of symbols, preposterous human interactions, and rhetorical inflation that threaten to sink so much of that period writing in Europe. And for that matter the visual arts. This volume is illustrated with spidery drawings by Alfred Kubin (1877-1959), who practiced an art of derangement. At least Freud had real dreams to mull over. Goethe gives us metaphors, Mynona gives us machinery. On the other hand, all the stage business, the dream corridors and magic mirrors, come to seem tongue in cheek, deliberately overplayed in a way that feels closer to Pere Ubu than to Georg Trakl.

There are moments in “The Creator,” however, when we catch some truly unsettling glimpses of the relation between the mind and the realities it alters. Gumprecht Weiss’s forays into dream corridors lead him circuitously back to his own room, where he can observe himself from a different state, so to speak. Until the Baron appears, Weiss hovers between worlds, unable to be certain which one he occupies. To my mind, this instability verging on a paranoid sense of entrapment hints at the path taken by the two greatest German prose writers to emerge from the Expressionist atmosphere of World War I, Franz Kafka and Hermann Broch. With the exception of Kafka’s “The Metamorphosis,” both writers steered away from the fantastic and the elaborately symbolic. Instead, they mobilized the objective and even quotidian language of the third person to create interior narratives of deeply alienated consciousness. Subject and object collapse in their different prose styles. Ominous and baffling, their stories seem far closer to the way dreams feel. In Kafka’s The Trial and Broch’s The Sleepwalkers, main characters struggle with the circumstances of reality that are to a great degree projections of their own inner turmoil. They cannot make the distinction between what is working in them and on them. They are precisely the opposite of the freely imagining subjects that Mynona celebrates. For as demonstrated by subsequent events in Germany – and current events in our own country – projecting one’s own will and desire onto the world and insisting on its independent reality is not liberation but a form of madness, and the origin of collective nightmares.

by Lyle Rexer