Black and White and Red: “The Krimson Kimono”

“I taste it right through every bone inside me.” This is a quintessential Sam Fuller line: there’s something off-kilter about it that might bug the literal-minded, but it’s a shot at conveying feelings so visceral and all-consuming that words can’t contain them, that language is warped by their intensity. The line is spoken by Joe Kojaku (James Shigeta) in Fuller’s The Crimson Kimono (1959). A nisei, or second-generation Japanese-American, Joe is talking about his sense of nationality and race, his experience of being truly American and at the same time feeling sickeningly different. Fuller’s movies are filled with these tortured and transcendent moments when people try to communicate their deepest realities—like Kelly in The Naked Kiss (1964) telling a young woman what it’s like to be a prostitute: “You’ll be sleeping on the skin of a nightmare for the rest of your life.”

What saves Fuller’s language and his style from seeming risibly overheated is this constant sense that he wants more from words and images than they can give, more from the senses than they can provide. He wants to make us not just see but taste and smell and feel the experiences onscreen. In long continuous tracking shots we move with the characters and inhabit their space, but abrupt cross-cuts between different scenes slice through the flow, and sudden extreme close-ups seem like an attempt to force us under the actors’ skins. His style is the cinematic equivalent of the way, as Wim Wenders describes it in a documentary about Fuller, he would tell stories: jumping on the furniture and grabbing your arm and pacing and shouting.

Fuller was a newspaperman, of course, the kind with ink in his veins, and his films recall that old chestnut about what’s black and white and “red” all over. The Crimson Kimono is shot in black and white, but it’s about seeing red—not only in the eponymous garment, worn by a stripper who has herself painted as a geisha, but in a plot that turns on people reacting violently to betrayals that turn out to be projections of their own insecurities, which blind them like a blood-red haze.

Filmed on location in downtown Los Angeles, The Crimson Kimono opens with a tabloid blare: a brassy fanfare of burlesque jazz over a glittering aerial shot of the city at night; a stripper running down the neon-lit streets half-naked, with her long blonde hair streaming, to be shot down on the asphalt. But the story that follows celebrates sensitivity, delicacy, and gentleness—qualities weirdly heightened and accentuated by Fuller’s punchy style. There is a direct cut from the lurid murder to a close-up of Joe looking introspective. He and his partner are questioning the slain burlesque performer Sugar Torch’s manager about the new Japanese routine she was planning—a compendium of clichés (geisha, samurai, karate) embellishing a strip act. Throughout the film, Japanese culture is exploited and respected, exoticized and taken for granted.

The investigation of Sugar Torch’s murder is merely a framework for the real heart of the film, a love triangle between the two cops assigned to the case and a young woman witness. The police detectives, Joe Kojaku and Charlie Bancroft (Glenn Corbett), are best friends with a blood-brother bond from their time in Korea. (Shigeta and Corbett were both making their film debuts, and brought a remarkable freshness and attractive sincerity to Fuller’s script.) When the partners interview Chris (Victoria Shaw), an elegant and self-possessed young painter who created the crimson kimono portrait and saw the man who is now the chief murder suspect, Charlie immediately falls for her. He’s a nice, uncomplicated guy with the square-jawed and clear-eyed looks of a star quarterback. Chris doesn’t repel his straightforward advances, but her real interest is fixed in a long, quiet scene where she and Joe get to know one another. He plays a delicate, melancholy Japanese children’s song on the piano (“Red Dragonfly”); they talk about a lacquer painting his father made, and about Chris’s art, how she is searching for something she hasn’t yet found. Here we see two serious, aesthetically sensitive people discovering a connection and mutual attraction, but Fuller caps the scene with a signature dose of hyperbole. Things seem to be building toward a kiss, but Joe declines to initiate it, saying, “Let’s not trigger off a bomb.”

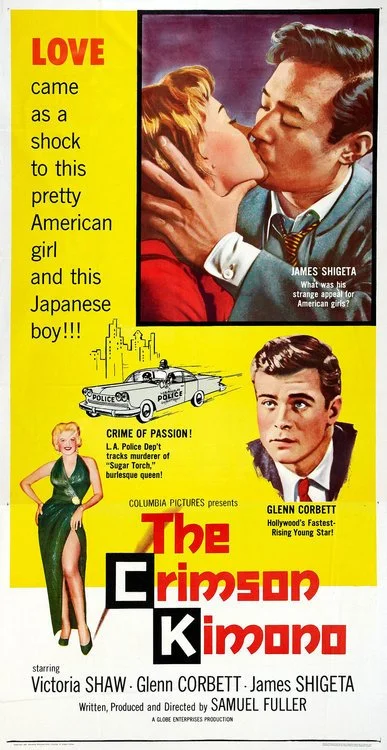

Fuller was adamant that Chris falls for Joe simply because they have a greater connection, more in common, better chemistry. The studio heads at Columbia insisted that unless the white guy was shown to be a son of a bitch, audiences would never accept the girl choosing the Japanese man. To his credit Fuller stuck to his guns, and he also included a passionate kiss between Chris and Joe, probably the first between a white actress and an Asian actor in a Hollywood movie. The studio did their best to undermine him with a laughably offensive ad campaign, showing an image of the kiss on posters with the tag-line: “YES, this is a beautiful American girl in the arms of a Japanese boy!” (Would miscegenation matter less is the girl weren’t beautiful?)

It’s often said that the film is about reverse racism, but—leaving aside the dubious validity of that term—it’s really about internalized racism: the way people who have been subject to prejudice can grow hyper-sensitive and perceive bigotry even where it’s not. Joe mistakes Charlie’s perfectly normal romantic jealousy for racism, assuming not only that his friend is nauseated by the interracial love, but that Charlie has secretly harbored racist feelings throughout their friendship. Charlie is justly outraged and hurt, and even Chris complains about how Joe’s self-consciousness and discomfort about his racial difference paralyze him. Joe’s anguish is out of all proportion to anything that has happened; the accumulated anger from a lifetime of small slights and stings explodes at this perceived betrayal. In a climactic exhibition kendo match, Joe disgraces himself by breaking all the rules and beating Charlie in a blind rage.

In a denouement that nicely ties the crime story together with the love triangle, the revelation of the culprit and motive behind the murder of Sugar Torch sparks an epiphany as Joe realizes that the distrust and rejection have been all in his mind. Though it unfolds amid the spectacular swirl of a street parade, with gunshots ringing out amid kimono-clad dancers and hanging lanterns, the climax is written on Joe’s face. Fuller has made a kind of action movie about the interior life.

But much of the film’s appeal also comes from its rich and strange setting, which straddles the tawdry realm of strip clubs and flop houses; the narrow alleys of Little Tokyo with their doll shops, noodle stands, bars, art galleries, temples and cemeteries; and the oddly artsy, bohemian atmosphere in which the two police detectives live. They share a surprisingly fancy pad, where Chris moves in to live with them after someone tries to kill her. This unlikely move is treated as perfectly normal—typical of Fuller’s plots, which like his dialogue are full of odd juxtapositions, gaps and gulfs in credibility, a general sense of slight distortion. This dreamlike, fevered quality is key to the power of his movies, in which contrasting moods or tones often mingle and overlap.

The ending of The Crimson Kimono is classically bittersweet. Joe is exultantly healed, but poor Charlie remains too pained by loss of Chris to reunite with his friend. There’s a mournful sense that they’ll never fully recover their closeness. Things don’t look too bad for Charlie, though, as he goes off to get drunk with his friend Mac (the lovely Anna Lee), a wry, hard-drinking bohemian artist who flavors the movie with her own eccentric wisdom, including the unforgettable aphorism:

“Love does much, but bourbon does everything.”

by Imogen Sara Smith