Everybody’s Wrong About Celine

Readers—especially the academic sort—who have read anything by or about Louis-Ferdinand Celine are in the bad habit of drawing some mighty extreme conclusions about him very quickly. He was a Nazi, they say, or insane, or just plain old Evil.

Unfortunately these people, who for the most part seem to have based their opinions on what others have told them, are wrong. (I would add “and stupid dumb-heads” there, too, but I’m trying to maintain a certain tone.)

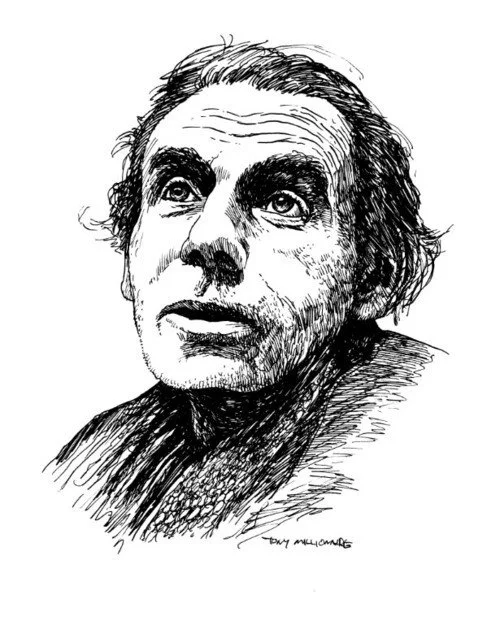

Celine was one of the most absurdly contradictory figures in literature, and today some fifty years after his death, he remains among the most hated. To understand why, we need to back up a ways.

Although born in France, Louis-Ferdinand Destouches (that was his real name, “Destouches”) was sent to boarding schools in England and Germany when he was growing up. At the outbreak of WWI, the 17 year-old joined (he says by accident) the French infantry and was sent to the front lines. In one of his very first battles a German mortar left him with a serious head wound and he spent the next year in the hospital.

After the war he went to medical school and got his degree. While most of his classmates went immediately into private practice (that’s where the money was), Destouches opened a free clinic for the poor in one of Paris’s worst slums, where he was often paid for his services in produce and chickens. In subsequent years he opened other free clinics in other slums.

A longtime lover of ballet (even writing several himself), Destouches married a ballet dancer. In 1932 with her encouragement and help, he published his first novel, Journey to the End of the Night under the name Louis-Ferdinand Celine.

(Not sounding like too bad a guy so far, right? Well hang on—things take a turn here pretty soon.)

The book was an overnight sensation, and Celine became a literary celebrity in Paris.

Focused on his wartime experience, the novel was a phantasmagoric, hallucinatory, quixotic black comedy, half-truth, half-fiction, and featuring a narrator named Bardamu. Hapless, deeply cynical, and funny, he navigates a wildly chaotic and filthy world full of outrageously stupid, hateful people. Bardamu despises everyone and everything—the French and Germans alike, foot soldiers as well as officers, the poor and the rich. No one escapes, not even the protagonist himself.

What caused such a stir wasn’t just the impenetrably black humor, but the style. Celine wrote a book unlike any other. The language was shattered into a series of sentence fragments connected by ellipses and ending in exclamation points. It seemed like stream of consciousness pushed to the extreme and shouted in the reader’s face. What’s more, Celine took the usual highfalutin “literary French” that was used in every novel and flushed it down the crapper, instead writing his novel in street slang—the colorful, obscenity-laden language of the gutters he heard around him every day at the clinic. It may be hell on translators today, but back in the early ‘30s it really blew folks away.

Celine quickly followed it up with another novel, Death on the Installment Plan, in which he wrote about his travels across Europe, as well as to America and Africa, and pushed that splintered style even further. It was no less dark, and solidified his reputation as a literary genius as well as the king of the misanthropes. This kind doctor who cared for the poor made it perfectly clear that he hated everyone, save for his wife and his cat.

Other books came out and Celine’s popularity grew. Then in 1937 everything changed.

Over in Germany Hitler was being all Hitlery, and everyone was getting the distinct feeling that another big war was coming. Celine felt it too, and was compelled to write three pamphlets. In spite of everything, he was still a proud and patriotic Frenchman. He told the people of France that a war was coming, and when it did, France should stay out of it. He’d seen war up close, he said, and knew that if France got involved in this next war, the nation would be devastated. In short, a man known for his nihilistic rage had written an anti-war message.

If he’d stopped there, everything would’ve been fine. But then he added (I’m paraphrasing here), “And by the way, who’s really behind this war? Who stands to profit from it? The JEWS, that’s who!”

Well, just as quickly as he’d become the greatest hope of French literature, Celine was the most hated man in Paris. Book sales plummeted, he was attacked in editorials, nobody wanted anything to do with him anymore.

Then the war came, Germany invaded France, and Celine pledged his allegiance to the Vichy government. This did not help his popularity.

Here’s the thing, though. The general argument is that Celine was driven to become a collaborator by his deep hatred for the Jews. To this day he is considered a Nazi and a virulent anti-Semite because of the move. More recent academic types have argued (with straight faces, no less) that the head wound he received during the war left Celine insane, and this explains both his behavior as well as his increasingly ‘incoherent” writing style.

Both are awfully simple explanations. My own explanation is simpler still.

As for his writing, Celine wrote a book, Conversations With Professor Y, in which he explains exactly what he’s doing and why. If you read all the novels in chronological order, you can watch the progression of this style, and see for yourself that it makes perfect sense. So much for that argument. Then there’s the Jewish question.

I’m not about to claim that Celine didn’t hate Jews. He most certainly did. But he also hated everyone else. He thought the Germans were oafish buffoons. He hated Americans and Brits and Christians and Hindus—take your pick. Roll the dice, he hated them. He had little use for authorities or organizations or governments, either.

No, Celine signed on with the Vichy government out of bitterness and spite. He’d warned France to stay out of it, they didn’t, and what he claimed would happen turned out to be exactly what happened. What’s more, they turned on him for what he’d written, and in so doing revealed themselves as even bigger hypocrites than he realized.

Historically France has always been one of the most openly anti-Semitic nations in Europe, so why turn on him for pointing it out? Becoming a collaborator was simply Celine’s way of saying “fuck you” to a nation he loved and had been trying to protect. If they wouldn’t listen to him, then they get what they deserve. He insisted to the end that he was more a patriot than the people who’d turned in him.

After the war, Celine (then on the lam with his wife and his cat) was tried in abstentia, found guilty of treason, and sentenced to hang. Only a last minute plea from some prominent literary figures spared him. Instead of being hanged, he was exiled to a small villa to the north, hundreds of miles away from his beloved Paris. He never forgave anybody.

As his work progressed the amount of vitriol aimed at the Jews only increased. I tend to think this has less to do with any particular, singular hatred he felt, than the result of Celine playing a ole as a cartoonish Jew-hating monster. If that’s what pissed the hypocrites off most, that’s what he would give them. At some points it became so over the top it’s hard to take very seriously.

As one story goes, for instance, Allen Ginsberg and William Burroughs made a pilgrimage to his compound to meet Celine. As they entered the gate, thy found themselves surrounded by Dobermans. When Celine came to meet them, he explained that he was training the dogs to “kill Jews.” Ginsberg was not harmed during the encounter.

Celine died in 1961, the author of a dozen novels, several pamphlets and essays, one play, a handful of ballets, and no apologies.

by Jim Knipfel