Death in Venice, California

On February 1, 1963, Night Tide lapped like an expressionist wave against the screens of American drive-ins and art houses, not to mention the Times Square grind house where Truman Capote saw, and absolutely treasured, Curtis Harrington’s 1961 opus. Night Tide rolls in with the satiny force of its leading lady, Linda Lawson, whose breathy voice expresses alien intensity lurking behind an opaque curtain of melancholia.

It had spent three years languishing in the can when distributor Roger Corman smuggled the unlikely masterwork into public consciousness, another of his now legendary mitzvahs to art. Throughout Night Tide, a strangely hushed invitation lingers in the air: "Come live above a merry-go-round, have breakfast with a hot sailor and an even hotter mermaid, spend hours with an old drunk captain, listening to the strange tales behind the morbid souvenirs of his life.”

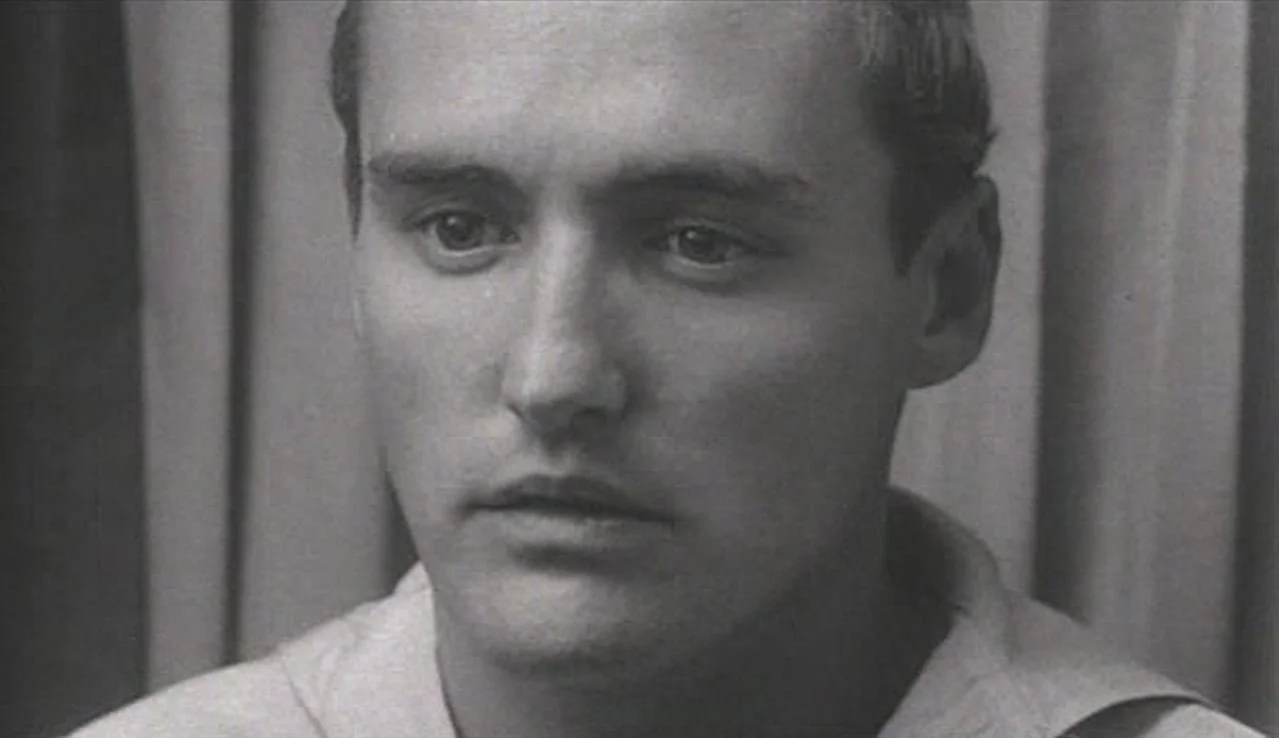

You, as a mere moviegoer, can walk away from this many-handed welcoming, and all the mystery it promises. Harrington's protagonist cannot. Like smoke, the truth gets in his eyes. Intense, somewhat myopic — they seem to be always focused on distances beyond the frame. Deeply hollowed under a very straight brow, so they peer out warily like a cave-dweller’s, wondering if this was such a good idea, and considering a strategic retreat. Even then he is every bit the director.

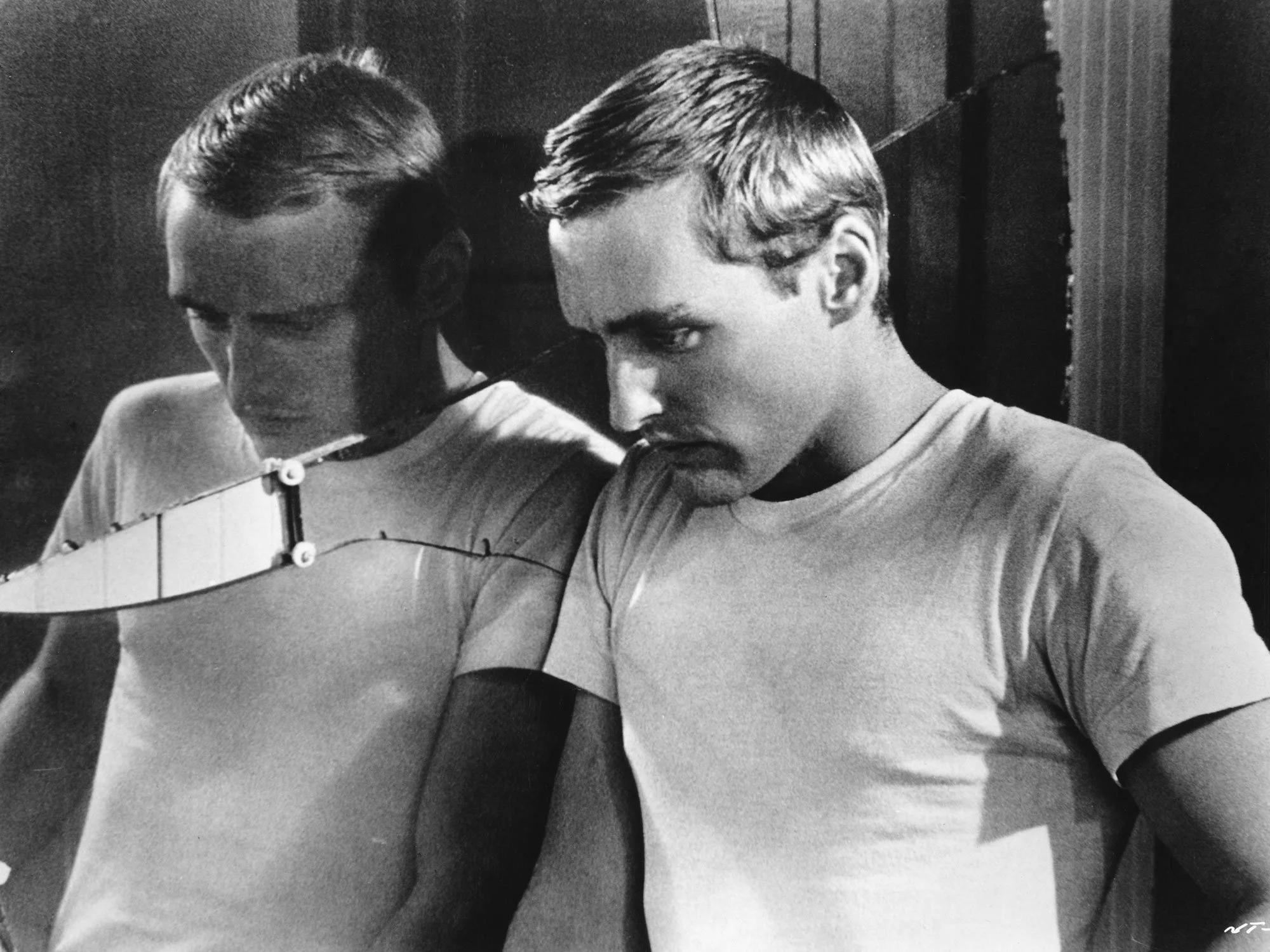

Dennis Hopper is young in Night Tide. Yes. Impossibly young for those who know him only from his titanic second act’s intrusion on the American consciousness in David Lynch's Blue Velvet, or even the grizzled nothing that his second act ultimately offered before he breathed his last. Then again, one could say the same about a very young and hot Bowser from Sha Na Na, or a very young Peter Lorre. Some eyes are evocative, plain and simple; pieces of brain that have burrowed to the surface. Nonetheless it is here, stuck in a tight-assed sailor's suit and plastered on God only knows what for much of the film's production, a Young Mr. Hopper, recently emerged from James Dean's often risible shadow, trains his vision as a reluctant American druid might; as if it were not just Curtis Harrington's movie after all.

They would meet again in outer space, three years after Night Tide confounded drive-in moviegoers throughout America. Yet, as if deliberately, perversely, laying waste to a collaboration that had unearthed so many riches, Harrington elected to give his now 30-year-old star nothing meaningful in which to display his talents. Queen of Blood (1966) finds Hopper, an ironic grin on his lips — the precise inspiration for which should best remain unknown — contentedly somnambulating through the skimpiest of roles, when he's exsanguinated by a mint-green space vampire.

For Curtis Harrington, Queen of Blood represented one step too far into the kingdom of low-rent kitsch. The lush sets and seductive color schemes, all of which was residue from a cannibalized Soviet space opera, cannot rescue what was ultimately no more than a typical AIP recut job. Harrington’s sensibility, here asserting itself only by its absence, demands rarefied air wafting through the schlock — Edgar Allan Poe blowing inspirational kisses — far-reaching vibrations and implicit metaphysical questions. Throughout his career, Harrington would rely on such to brace himself against the endless pitfalls of junk film-making. There was no more perfect example of this balancing act than Night Tide. Despite its scant budget and dubious standing (it was, after all, his first attempt at a commercial feature) Harrington managed to captivate long-established Hollywood eminences, like cinematographer Floyd Crosby (Tabu) and composer David Raksin (Laura, The Bad and the Beautiful). Their contributions keyed with surprising sensitivity to an all-embracing place-ness, the feeling that the cast, the script, everything on the screen, is synonymous with the rotting, low-horizon dream that Venice Beach had become: a gaudy ruin, irreplaceable yet destined for erasure, the memory of an adolescent USA greased for the skids of late-stage capitalism.

Casting our perspective some six decades after the fact, it comes as no surprise that the in loco parentis film critics of America would largely assume radio silence. After all, Night Tide evinces a radical and, if you prefer, anachronistic conception of identity — the rickety ballet of anima and animus — that, through the vehicle of Maya Deren, had laid siege to Curtis Harrington’s filmmaking since the post-war years, causing it to spark and spasm; a work more fanciful and to the point than any pornography ever filmed.

Harrington’s student opus, Fragment of Seeking (1946), had left one professor in USC's Cinema department so stricken that the young auteur was handed a more or less prosaic thank you for his effort and quietly dismissed. This film, with its ruthless blend of confession, confrontation, naïveté and incidental reportage, remains one of the singular creations in the strange, troubling canon of student filmmaking, and wholly unthinkable within the so-called ethics of mid-century USA. Its dream-jumble was born out of the same West Coast wellspring that brought forth the psycho-drama self-portraits of Deren, Sidney Peterson, James Broughton and Kenneth Anger, with its psychically harrowing fusion of male and female characters, while completely devoid of ironic distance or exploitive cynicism, as if its chief aim were the dualism of the ancients.

Fuck the ancients. As he shot Touch of Evil in and around Los Angeles' Venice Beach on a handful of nights in the early spring of 1957, Orson Welles would bashfully drape those trashy, less cinematic elements of the Mediterranean counterfeit before him in a voguish noir frock coat; one that would, at once, revel in the inherent ghastliness of such a place while concealing its full absurdity from eyes that would never be able to handle the contradiction.

Some years later, fate would conspire to choose Curtis Harrington, a cross-dressing Poe fanatic, to fully capture “The Slum by the Sea” with all its ravaged whimsy set against the lyric humiliation of once-ostentatious digs and the ruined face of spent oil wealth. Singularly unembarrassed by what he saw, Harrington gave audiences a Venice Beach that Welles would not: the sun-dappled occult, the queer, the criminal; a true, flophouse-ridden glory bathed in the endless California sunlight.

Night Tide assembles a distinguished skid row where underworld docents by the dozen pop into being with dazzling efficiency. Picture one thousand elves rising with glee to the same, single-minded curatorial task and you'll have a sense of what is involved here. In other words, as a demiurgic force, Harrington does not emerge from nothingness. After two decades fruitlessly bashing his head against the avant-garde wall, our schlockmeister arriviste goes Hollywood — that is, any imaginable “Hollywood” rude enough to splotch him with flat soda or leave him smelling of hot gravel and exhaust fumes.

The 60th anniversary of Night Tide’s popular release summons Linda Lawson (1936-2022). A well-known jazz chanteuse and recording artist, she does not sing here, and does not need to, the simplest and most serenely spoken word inducing synesthetic visions. Tinted, toned and extremely tactile, Black & White cinematography births color. We “hear” indigo satin, and the satiny smoothness of Poe’s lost love — Annabelle Lee — working sideshow hustles.

Every incantatory syllable escaping Ms. Lawson’s lips spawns a half-dozen seances.

It’s the presence of its featured players — certainly not their star power — that lends the film its haunting and enduring legacy, and elevating it from “cult classic” to its rightful place in the pantheon of cinema. Despite that, I argue that Night Tide remains outside of these exclusive parameters — upholding an elsewhere-ness that defies commercial, if not strictly canonical, logic. Curtis Harrington’s first feature film escapes taxonomy, typology, or genre, instead fueling itself on acts of solidarity. If Hopper contributes his dreamy aura, then Corman rescued the seemingly doomed project by re-negotiating the terms of a defaulted loan to the film lab company that prevented the film’s initial release. His generous risk-taking birthed a movie monument that would add Harrington’s name to a growing collection of talent midwifed by the visionary schlockmeister responsible for nursing the auteurs of post-war American cinema. And here we enter a production history as gossamery as Night Tide itself.

Unlike his counterparts entrenched within the studio system, Harrington was an artist — i.e. a Hollywood anachronism, with aristocratic grace and a viewfinder trained on the unseen. I see Harrington as Georges Méliès reborn with a queer eye, casting precisely the same showman’s metaphysics that spawned cinema onto nature. By the time moving pictures were invented, artists were moving away from its bloodless representational ethos and excavating more primordial sources for inspiration. The early stirrings of what surrealist impresario André Breton would later proclaim: “Beauty will be CONVULSIVE, or it will not be at all.”

Harrington owned a pair of Judy Garland’s emerald slippers, and according to horror queen/cult icon Barbara Steele, had also amassed an eclectic array of human specimens: “Marlene Dietrich, Gore Vidal, Russian alchemists, holistic healers from Normandy, witches from Wales, mimes from Paris, directors from everywhere, writers from everywhere, and beautiful men from everywhere.” On a hastily constructed Malibu boardwalk, Hopper would be in his milieu among the eccentric denizens of California’s artistic underground—most notably, Harrington himself, a feral Victorian mountebank of a director who slept among mummified bats, practiced Satanic rites, and hosted elaborate and squalid dinner parties. One could almost picture the mostly television director in his twilight years as Roman Castevet of Rosemary’s Baby; a spellbinding raconteur with a carny’s enticing flair for embellishment. Enthralled by the dark gnosticism of Edgar Allan Poe that had started when the aspiring 16-year-old auteur mounted a nine-minute long production of The Fall of the House of Usher (1942), Harrington would embark on a checkered film career that combined his occult passions with the quotidian demands of securing steady employment. Night Tide, a humble matinee feature whose esoteric underpinnings would spawn subsequent generations of admirers, united the competing forces of art and commerce that Harrington would struggle with throughout his career. Like Méliès, Harrington pointed his kinetic device towards the more preternatural aspects of early motion pictures to seek out the ‘divine spark’ that Gnostics attribute to transcendence, and the necessary element to achieve that immortal leap into the unknown. What hidden meanings and unspeakable acts Poe had seized upon in his writing were brought infernally to life with a mechanical sleight-of-hand. It was finally time for crepuscular light, beamed through silver salts to illuminate otherworldly and other-thinking subjects.

By the time Harrington had embarked on his feature film debut, a more muscular celluloid mythology based on America’s proven exceptionalism was in full force, taking on a brutalist monotone cast in keeping with the steely-eyed, square-jawed men at the helm of a nascent super-power, consigning its more feminine preoccupations to the dusty vaults where film gets devoured by its own nitrate. Harrington would resurrect the convulsive aspects of his chosen vocation and embed them deep within the monochrome canvas he’d been allotted for his first venture into feature filmmaking, while combining them with the more rational aspects of so-called realism. In the romantic re-telling of a familiar myth, Harrington was remaining true to his gnostic roots and to the distinctly poetic language used to express its cosmological features.

In Night Tide, Harrington maps the metaphysical terrain that held up Usher’s cursed edifice as a blueprint for his own work that similarly explored the intertwined duality of the natural and the supernatural. The visible cracks that reveal a fatal structural weakness and a loss of sanity in both Roderick Usher and his doomed estate are evident in Night Tide’s conflicted heroine compelled to choose between her own foretold death underwater or a worse fate for those who fall in love with her earthly human form.

A young sailor (Dennis Hopper) strolling the boardwalks of Venice Beach while on shore leave offers the viewer an opening glimpse into the film’s metaphysical wormhole — a not so subtle hint of the director’s queer eye — stalking his virginal prey in the viewfinder. A beachfront entertainment venue is, after all, where one would casually encounter soothsayers and murderers, sea witches and perverts, as indeed the guileless Johnny does, seemingly oblivious to the surrealist elements of his surroundings as he makes his way on land.

Harrington’s carnival-themed underworld is both imaginatively and convincingly presented as a quaint slice of post-war America, effortlessly dovetailing with his intended drive-in audience’s expectations of grind house with a dash of glamor, not to mention his own avant-garde leanings, which remain firmly intact despite Night Tide’s outwardly conventional construction and narrative.

Harrington is more than capable of presenting this juxtaposition of American kitsch with the queer arcana of his occult fascinations. Indeed, Night Tide’s lamb-to-the-slaughter protagonist could have wandered off the set of Fireworks, Kenneth Anger’s 1947 homoerotic short film about a 17-year-old’s sadomasochistic fantasies involving gang rape by leathernecks.

Anger would later sum up his early film as “A dissatisfied dreamer awakes, goes out in the night seeking a ‘light’ and is drawn through the needle’s eye. A dream of a dream, he returns to bed less empty than before.” Harrington (a frequent collaborator of Anger’s in his youth) seems to have re-worked Fireworks, or at least its underlying queer aesthetic, into a commercially viable feature film that explores his own life-long occult fascinations.

Both Anger and his former protégé would view the invocation of evil as a necessary step towards the attainment of a higher level of consciousness. Harrington coaxed a more familiar story from the myths and archetypes that informed his otherworldly views for a wider audience, a move that would be later interpreted by sundry cohorts as selling out. Still, Night Tide shares a thematic kinship with Anger’s more obtusely artistic output as acknowledged by the surviving occultist, who confirmed this unholy covenant at Harrington’s funeral by kissing his dead friend on the lips as he lay in his open coffin.

The hokey innocence of Dennis Hopper as Johnny Drake in his tight, white sailor suit casts a homoerotic hue on the impulses that compel him to navigate a treacherous dreamscape to satisfy his carnal longings, just as Anger’s dissatisfied dreamer obeys the implicit commands of an unspeakable other in search of forbidden pleasures.

As he makes his way on land, the solitary, adventure-seeking Johnny will be lured into a photo booth, his features slightly menacing behind its flimsy curtain, and then brightly smiling a second later as the flash illuminates them. Johnny has entered a realm where opposing worlds collide, delineating light from shadow, consciousness from unconsciousness. The young sailor’s maiden voyage into the uncharted waters of his subconscious is made evident in the contrasting interplay captured by the camera, where predator and prey overlap in the darkness. Here, too, we get a prescient preview of the deranged psychopath Hopper would subsequently personify in later roles, most significantly as the oxygen deprived Frank of Blue Velvet—a man who seems to be drowning out of water. But here, Hopper convincingly (and touchingly) portrays a wide-eyed naïf, still unsteady on his sea legs as he negotiates dry land.

As a variation of Anger’s lucid dreamer in Fireworks (and later Jeffrey of Blue Velvet) Johnny will have abandoned himself quite literally (as his departing shadow on a carnival pavilion suggests, before its host blithely follows) to his own suppressed sexual urges; a force that eventually compels him towards denouement.

Moments later, inside the Blue Grotto where a flute-led jazz combo entertains, Johnny spots a beautiful young woman (Linda Lawson) seated directly across from him. Her restrained and almost involuntary physical response to the music mimics his own, offering the first indication of a gender ‘other’ residing in Johnny; an entombed apparition cleaved from the sub-conscious and projected into his line of vision. Roderick and Madeline Usher loom large in Harrington’s screenplay, and Usher’s Trans themes lurk invisibly in the subtext. Harrington is arguably heir apparent to Poe’s vacated throne, pursuing similar clue-laden paths and exploring the dual nature of the human and primordial creature poised just beneath the surface to devour its host.

The near literal strains of seductive Pan pipes buoyed by the ‘voodoo’ percussion sets the stage for Harrington’s reworking of the ancient legends of sea-based seductresses and their sailors lured to their watery graves.

Marjorie Cameron (or ‘Cameron’ as she is referred to in the opening credits) makes a startling entrance into The Blue Grotto as an elder of a lost tribe of mermaids seeking the return of an errant ‘mermaid’ to her rightful place in the sea. Cameron, a controversial fixture in L.A.’s bohemian circles, and one-time Scarlet Woman in the mold of Aleister Crowley’s profane muses, would later appear in Anger’s The Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome, and as the subject of Harrington’s short documentary The Wormwood Star (1956).

The inclusion of a real witch, along with a host of less apparent occult/avant-garde figures, is further evidence of Night Tide’s true aspirations, as well as its filmmaker’s subversive intent to sneak an art-house film into the drive-in, and to introduce its audiences to the heretical doctrine that had spawned a new generation of occult visionaries that find their sources in the work of Edgar Allan Poe. Decades later, David Lynch would carry that proverbial torch, further illuminating the writhing, creature-infested realm underlying all that innocence.

Johnny approaches the young woman who, seemingly entranced by the music, rebuffs his attempts at conversation but allows him anyway to sit down. Soon they are startled by the presence of a striking middle-aged woman (‘Cameron’) who speaks to Johnny’s companion Mora in a strange tongue. Mora insists that she has never met the woman before, nor that she understands her, but then makes a fearful dash from the club as Johnny follows, and eventually gaining her trust and an invitation for breakfast on the following day.

Mora lives in a garret atop the carousal pavilion at the boardwalk carnival where she works in one of the side show attractions as a “mermaid.” Arriving early for their arranged breakfast, her eager suitor strikes up a conversation with the man who runs the Merry-Go-Round with the help of his granddaughter, Ellen (Luanna Anders). Their trepidation at the prospecting Johnny becoming intimately acquainted with their beautiful tenant is apparent to all except Johnny himself, who is even more oblivious to Ellen’s wholesome and less striking charms. Even her name evokes the soul-crushing flat earth sensibilities of home and hearth. Ellen Sands is earthbound Virgo eclipsed by an ascendant Pisces. (Anders would have to subordinate her own sex appeal to play this mostly thankless “good girl” role. She would be unrecognizable a few years later as a more brazenly erotic presence in Easy Rider, helping to define the counterculture era of the Vietnam war.)

As Johnny ascends the narrow staircase leading to Mora’s sunlit, nautical-themed apartment, he almost collides with a punter making a visibly embarrassed retreat from the upper floor of the carousel pavilion. Is Johnny unknowingly entering into a realm of vice and could Mora herself be a source of corruption? Her virtue is further called into question when she not so subtly asks Johnny if he has ever eaten sea urchin, comparing it to “pomegranate” lest her guest fail to register the innuendo, as obvious as the raw kipper on his breakfast plate. Johnny admits that he has never eaten the slippery delicacy but “would like to try.” Moments later, Mora’s hand in close-up is stroking the quivering neck of a seagull she has enticed with a freshly caught fish, sealing their carnal bond.

Their subsequent courtship will be marred by an ongoing police investigation into the mysterious deaths of Mora’s former boyfriends, and her insistence that she is being pursued by a sea witch seeking the errant mermaid’s return to her own dying tribe. Her mysterious stalker will make another unwelcome entrance after her first appearance in the Blue Grotto—this time at an outdoor shindig where the free-spirited young woman reluctantly obliges the gathered locals urging her to dance. The sight of ‘Cameron’ observing her from a distance causes the frenzied, seemingly spellbound dancer to collapse, setting off a chain of events that will force Johnny to further question her motives and his own sanity.

Mora’s near death encounter through dance pays homage of a sort to another early Harrington collaborator and occult practitioner. Experimental filmmaker Maya Deren had authored several essays on the ecstatic religious elements of dance and bodily possession, and went on later to document her experiences taking part in ‘Voudon’ rituals in Haiti that would be the basis of a book and a posthumously released documentary, both titled Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti. Note the Caribbean drummers whose ‘unnatural’ presence, in stark contrast to the more typical Malibu beach party celebrants, hint at the influence of black magic impelling the convulsive, near heart-stopping movements that eventually overtake her ‘exotic’ interpretive dance.

The opening sequence of Divine Horsemen includes a woodblock figure of a mermaid superimposed over a ‘Voudon’ dancer. The significance of this particular motif was likely known to Harrington, a devotee of this early pioneer of experimental American cinema. Deren herself appeared as a mermaid-like figure washed ashore in At Land (1947), who pursues a series of fragmented ‘selves’ across a wild, desolate coastline. Lawson, with her untamed black hair and bare feet, could be Deren’s body double, an elemental entity traversing unfamiliar physical terrain to find a way back to herself.

Mora’s insistence that she is being shadowed by a malevolent force directly connected to her mysterious birth on a Greek Island and her curious upbringing as a sideshow attraction compel Johnny to investigate her paranoid claims, hoping to allay her fears with a logical explanation for both. The sea witch (or now a figment of his imagination) will guide the sleuthing sailor into a desolate, mostly Mexican neighborhood, where her departing figure will abandon him right at the doorstep of the jovial former sea captain who employs Mora in his tent-show as a captive, “living, breathing mermaid.”

The British officer turned carny barker is in a snoring stupor when Johnny first encounters him, snapping unconsciously into action to give a rote spiel on the wonders that await inside his tent. Muir balances Mudock’s feigned buffoonery with a slightly sinister edge. When Johnny arrives at his doorstep to find out more about the ongoing police investigation into her previous boyfriend’s deaths, the captain’s effusive hospitality takes on a decidedly darker tone when he guides his visitor to his liquor/curio cabinet where a severed hand in formaldehyde, “a little Arabian souvenir,” is cunningly placed where Johnny will see it. The spooky appendage serves as a reminder to Mora’s latest suitor of the punishments in store for a thief.

Captain Murdock’s Venice beach hacienda is yet another one of Night Tide’s deviant jolts: a fully fleshed out character in itself that speaks of its well-travelled tenant’s exotic and forbidden appetites. This dark, symbol-inscribed temple at 777 Baabek Lane could be a brick-and-mortar portal into this mythic, mermaid-populated dimension that Johnny’s booze-soaked host thunderously defends as real.

Before falling into another involuntary slumber, Murdock will try to convince Johnny that, while he and Mora merely stage a sideshow illusion —“Things happen in this world”— Mora’s belief that she’s a sea creature is grounded in fact.

Murdock’s business card that Johnny handily has in his pocket while tailing his dramatically kohl-eyed mark is oddly inscribed with an address more likely to be an ancient Phoenician temple of human sacrifice (Baalbek) than a Venice Beach bungalow. A lingering close-up offers another tantalizing, occult-themed puzzle piece — or perhaps a deliberate Kabbalah inspired MacGuffin. The significance of numbers as the underlying components for uniting the nebulous and intangible contents of the mind with more inert, gravity bound matter, existing outside it, as the ancient Hebrews believed, wouldn’t have been lost on Night Tide’s mystically-minded helmer. Mora’s explicitly expressed disdain for Johnny’s view of the world as a rationally ordered, measurable, mathematically explained phenomenon reinforces Harrington’s own world-view, his love of Poe, and the French Symbolist artists that interpreted him.

In Odilon Redon’s Germination (1879), a wan, baleful, free-floating arabesque of heads of indeterminate gender suggests either a linear, ascending involution, or a terrifying descent from an unlit celestial void into a bottomless pit of all-too-human, devolving identity. Redon’s disembodied heads gradually take on more human characteristics, culminating in a black-haloed portrait in profile. The cosmos of Redon’s lithograph is governed by unexplained, inexplicable moral sentience absorbing the power of conventional light. Thus black is responsible for building its essential form, while glimmers of white, hovering above and below, prove ever elusive; registering as if elsewhere, beyond the otherwise tenebrous unity of the picture plane.

Of course, Night Tide has its own unsettling dimensions — this black-and-white boardwalk where astral, egalitarian bums wish to tip-toe along and, somehow, practically all of them do. Not a movie but an ever-becoming place crammed into low-budget cosmogenesis unto eternity. We won’t discuss the ending here, since it hasn’t happened yet.

Scratching remembrances in longhand for the director's 2007 funeral, cult deity Barbara Steele reminds us of Curtis Harrington’s essential gentleness, despite his depraved dinner parties summoning imperial decadence, scenes out of Hogarth. “Once you were inside his charmed circle you would never be banished,” writes Steele, apparently likening the deceased to a fanciful and ramshackle movie set — fashioned by his own living hands — “it was such a delightful place to be, you wouldn’t want to escape… and you loved him with all your heart.” Well, doesn’t that selfsame pas de deux delineate Night Tide's inner world: unwonted inhabitants and mainstream audience (lovingly dragooned), like two bodies joined in a single swirling embrace? Or, if you prefer, the grim and grimy palimpsest of a historical setting ready for its close-up.

By the 1930s, with oil rigs springing up like industrial dandelions, Venice Beach — unveiled a quarter century earlier as "Venice of America," and still called, with a straight face, a Peninsula — was an all-American eyesore. Built upon reclaimed swampland, this one-time dreamscape of would-be aesthete, Abbot Kinney, was now largely abandoned, even by its tourists.

“Venice, California", Ray Bradbury would one day write, casting perspective with an unmistakable degree of awe, "had much to recommend it to people who liked to be sad. It had fog almost every night and along the shore the moaning of the oil well machinery and the slap of dark water in the canals and the hiss of sand against the windows of your house when the wind came up and sang among the open places and along the empty walks." Death is a Lonely Business, Bradbury's 1985 novel, is set in 1949 and, certainly without meaning to, evokes a film that neither states its own origin-story nor seems to imagine anything else beyond its own expressionist visions of a churning sea:

"At the end of one long canal you could find old circus wagons that had been rolled and dumped, and in the cages, at midnight, if you looked, things lived, fish and crayfish moving with the tide; and it was all the circuses of time somehow gone to doom and rusting away.”

Let’s end our meditation, equal parts sad and celebratory, by raising a toast to Venice… And to the sleazy-sounding double bills that unleashed an aberrant wonder… Night Tide’s compact leading man, a force previously held captive by the studio system appeared like some homunculus refugee from the Fifties USA. Dennis Hopper, in his first starring role, would later recall that it represented his first “aesthetic impact” on film since his earlier appearances in more mainstream productions, such as Rebel Without a Cause and Giant, had denied him meaningful outlets for collaboration. Keep your eyes open for the erstwhile muse to surrealist filmmaker Jean Cocteau. Barbette, who often appeared en travesti, might otherwise get lost amidst the anonymous, teeming extras. A tarot reading at the film’s heart gives Marjorie Eaton her time to shine, traipsing into nickel-and-dime divination from her former life as a painter of Navajo religious ceremonies. Bruno VeSota gets a cameo (that uncredited punter on the stairs).

Linda Lawson might have been issued from a lithograph by Odilon Redon, with her raven locks and spiritual eyes, she is our resident sideshow mermaid.

Night Tide was released sixty years ago today, emerging from the obscurity of its production into the deeper obscurity of near-universal neglect, but it has never quite sunk from the cinematic consciousness.

By Daniel Riccuito

Special thanks to Jennifer Matsui, Tom Sutpen, David Cairns and Richard Chetwynd