Eleanor Powell

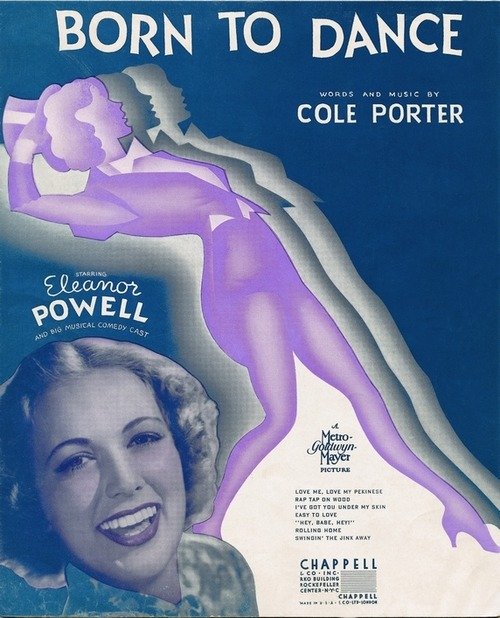

One of her movie vehicles was called Born to Dance (1936), and if ever anyone was, surely it was Eleanor Powell, the queen of tap. Fred Astaire said that Powell laid down taps “like a man,” and that’s a clue to both her appeal and also her limitations. Powell made only 14 features, nine of them as a star or headliner, from 1930-1950. She did a lot of numbers in men’s suits, her eyes rolling with what seemed like pleasure and her mouth as wide open as possible in a smile, even when she was coming out of a series of turns that might have made Ann Miller feel like she needed to sit down. She would often do backbends, splits and acrobatic work in between her taps, all with that toothy grin on her face.

“I would rather dance than eat!” Powell said in a rare late interview. She claimed that she was so shy as a child that her mother sent her to dance school as a way to get over it. Powell looked down on tap at first, but then she was taught by Jack Donahue, who had partnered Marilyn Miller, and his technique intrigued her and defined her own later style. “He had a belt from the war-surplus store and he took two sandbags—the kind they use in theaters for curtains—and he put one on each side of the belt, which he fastened around my waist,” Powell said. “Honey, I was riveted to the ground. That’s why I dance so close to the ground. I just couldn’t move. That’s why I can tap without raising my foot even, because I was taught with this belt and these weights on me.” Her shapely legs seemed stuck to the floor always, and this gave her an extraordinary sense of balance; there was no way she was ever going to shift her weight or be in danger of falling over. She had a physical rootedness that was very similar, sometimes, to Gene Kelly’s own close-to-the-ground, masculine dancing.

Powell danced in nightclubs and on Broadway and made a screen debut in Queen High (1930), where at 17 she danced in her scanties on top of a table and wore a Louise Brooks bob. When you see and hear her tap (the camera cuts her head off for a bit), it’s clear that this isn’t just another hotcha girl; her taps on the table have a solidity that already seem formidable. They would still seem that way five years later at Fox, in George White’s 1935 Scandals, where she has a bit of a part and does a specialty number, the camera cutting to a close shot of her feet as they tapped and barely left the floor. Powell remembered that she was “almost a little prissy, if you want to know the truth,” and was unhappy about male cast members like James Dunn and Ned Sparks drinking on the set.

She had an ironclad kind of wholesomeness that marked her as suitable for MGM, where she was signed and starred in her own series of films, beginning with Broadway Melody of 1936 opposite Robert Taylor. Her singing voice was usually dubbed, but not always, and her acting was game but awkward (though she is pretty funny doing a Katharine Hepburn impersonation in that first MGM film). When she dances, and even in dialogue scenes, her face sends out signals that she can’t seem to control that look like brash sexual come-ons, yet everything else in her manner denied them.

Jimmy Stewart made for an ideal hayseed partner for her in Born to Dance, singing to her sweetly in his thin voice and then giving way to what would become a standard part of her films, a big finale where she would wear some kind of uniform and turn and turn. The settings and extras behind her grew larger and grander with each movie, until in Rosalie (1937) she spins down some large drums and winds up on a stage where all of Hollywood seems to be gathered behind her and the camera pulls back further and further, as far back as it will go. Her finales became overblown and overproduced in a willful way, as if MGM thought audiences were paying to see money spent as flagrantly as possible. Powell smiled through it all while her body worked its virtuosic wonders.

In Honolulu (1939) she does a kind of hula tap and a very cheerful number with Gracie Allen where she dances while jumping rope. The zenith of her career was her partnership with Astaire in Broadway Melody of 1940, particularly the tap conclusion to “Begin the Beguine,” two minutes and 51 seconds of perfection. When she advances on him and does a light kick, it’s cute rather than Cyd Charisse-sexy; unlike Charisse or Ginger Rogers or Rita Hayworth, Powell scrupulously has no sexual charge whatever. (It’s a shame that she never got to dance with Gene Kelly, who was once scheduled to do a Broadway Melody film with her, for he might have given her a bit of sex from his own surplus.)

Astaire himself seems delighted to have such an equal partner, but they’re so similar that there’s no friction between them, and they almost cancel each other out. That “Beguine” tap is so rarified that it’s nearly cold, but Astaire and Powell have an awareness of just how far they’re going together that warms it just enough to make it a major, essential dance. Their tap side by side, trying to match and then outdo each other, is beyond words, and the most marvelous transition is when their taps get lighter and lighter momentarily, about two minutes in, and then suddenly come back strong and pound the floor decisively. This is her ticket to immortality, and it makes all of Powell’s gaucheries and solo gimmick dances not matter at all. A moment she has in another number in this movie epitomizes her overall character: after an extremely difficult set of acrobatics, she stands and salutes the camera and then quickly brushes an out-of-place hair behind her ear. Something like that indicates that nothing was going to be allowed to mar the picture she wanted to present, her superhuman image of control. Greta Garbo and Joan Crawford, she said, would come and watch her dance for hours, presumably because her authority relaxed their very different anxieties.

There were a few more films and solos to come. She does a charming dance with a dog she had trained herself in Lady Be Good (1941) and a galvanizing routine with drummer Buddy Rich in Ship Ahoy (1942). “A tap dancer is nothing but a frustrated drummer,” she said. “You’re a percussion instrument with your feet.” In her last three films, she was back to being a specialty act, and that’s mainly because she couldn’t do romantic partner dancing or romantic anything; it’s no mistake that her last vehicles paired her with that woeful would-be laugh-getter Red Skelton.

She married Glenn Ford, had a child, and retired save for a religious program she did on TV for a bit. In the early 1960s, her son encouraged her to pursue nightclub work, but once Powell proved she could do it and still be successful she retired again, only to emerge one more time for the American Film Institute Lifetime Achievement Award ceremony for Fred Astaire in 1981, where she received a standing ovation. In that brief footage at Astaire’s AFI tribute, Powell reveals herself as an old-time show business trouper socking it to the audience, like Sophie Tucker, who she had worked with as a girl. She proudly says that she and Astaire worked for two weeks on just their arm movements for “Begin the Beguine,” just so that they would be perfectly in synch. Powell seems hearty and proud here, ending her little speech with an arms-out physical tribute to Astaire as one “hoofer” to another.

Powell didn’t have the complexity of Ginger Rogers or the sexual dazzle of Cyd Charisse, or even the warmth of Ann Miller. She was just perfect, that’s all, and that could be too much, sometimes, but in “Begin the Beguine” with Astaire, she offers a privileged glimpse of something nearly otherworldly. As she might have said, she had been given a gift by God, and now she was offering her own gift in return, and in this partner dance with Astaire very few artists have ever made such an offering.

by Dan Callahan