FROM BROADWAY TO BOMBAY: Marty Reisman (1930-2012)

In the late 1990s I worked at a small used bookshop on Fourth Avenue. A lot of unusual printed matter passed through the stacks. One time a writer for the Village Voice sold us his book collection, which included a copy of The Money Player: The Confessions of America’s Greatest Table Tennis Champion and Hustler (1974), by Marty Reisman.

Naturally, I took the book home and read it. I wasn’t that good at ping-pong but always enjoyed the leisurely workout and kerplockety-plock. Reading The Money Player, I learned that table tennis had once served the performance art of a Manhattan toff and postmodernist swashbuckler.

Marty’s book is a ripsnorting memoir of old New York and a life spent hustling ping-pong “from Broadway to Bombay.” The Money Player matured in Times Square gaming parlors where sharpers mad for mazuma high-rolled and lowballed. He traveled the world upon his surpassing brinksmanship as a table tennis sizzler, and recounts stories of smuggling gold out of Hong Kong, and posing as a butterfingers baby crib salesman in Nebraska to sap a paddle-chump out of twenty grand.

I wondered if Marty Reisman still lived in the city and if he still played.

Back at the bookshop, if a customer asked for something we didn’t have, we’d take their name and number in case a copy came in. Some months after reading Marty Reisman’s confessions, I returned to work after a day off to find his name and number newly inked in our file; he’d popped in the day before looking for a copy. The Money Player was a scarce tome after only one hardback printing.

Granted the uncanny chance to actually talk to the character, I dialed the 212 number. Marty answered with his low pulp paperback lilt and had me on the phone the next two hours, ingratiating and eager to spiel and reading excerpts from his new manuscript. His voice spun like his strike-of-a-match forehand drives, which in 1958 set a record at 110 MPH. I was invited over to his apartment to see his rich collection of antique microscopes.

We became friends and I often met Marty and his wife Yoshiko for dinner at Mee Noodle on the corner of 49th and 2nd Ave. Marty liked the shrimp with lobster sauce, ground pork and egg. He always brought us cold cans of Bud to wash down the chow. If we went for pizza, Marty ordered a slice and told the dough-slinger to “burn it.”

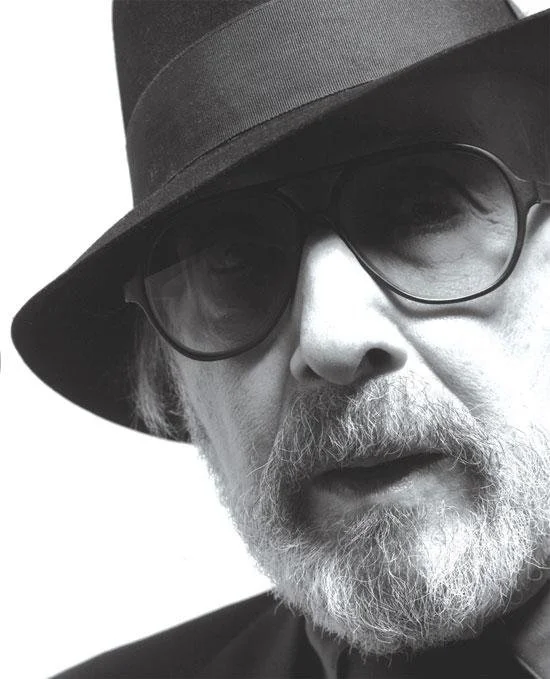

I went to several matches and saw Marty in action, playing benefit doubles with his cardiologist, a stocky and fierce batter. Marty wore his signature raiment of Panama hat, tinted shades, sporty starch-collared shirt, slim slacks, and red sneaks, with which he still might use in lieu of a paddle to fire the ball back over the net.

“Until the age of 12, I had lived a pretty full life,” Marty wrote, “I even had a nervous breakdown.”

Marty was born in New York during the Depression and grew up in the Lower East Side. Slight and thin, he was prone to nosebleeds, blind spells, and panic attacks. The doctor suggested that taking up table tennis would be good for his eyes. Marty began playing the game at the Educational Alliance on East Broadway and soon recognized he had the stuff.

Marty's father was a cabdriver and bookmaker and gambler with no luck. Marty says the old man once lost six taxis in a poker game. But he introduced his kid to an underworld of numbers and risk and Marty took to the action.

Back then, table tennis was a betting sport as viable as the racetrack or dice. Marty soon graduated from the schoolyard to the buzzard halls of the Glittering Gulch, where wagers hurled upon the future as if confetti on New Year’s Eve. Marty lived at the ping-pong tables and gave up going to school. The nosebleeds and blind spells and panic attacks ebbed. He hustled money by night and by day practiced at Lawrence's Broadway Table Tennis Club, a former speakeasy with bullet holes in the wall. He derived education from the venues and characters in the neighborhood, the crapshoots and marquees and greasy spoons, the backgammon tables and knockabout acts and shooting galleries, the chorus girls, finks, jarheads, weisenheimers, City College professors, night owls, card sharks, and muggers of old ladies.

“No one has ever been less suited for regular employment than I was.”

Young Marty brandished the hardbat against men twice his age and got used to winning. He learned to abide the gospel his father never could: bet only on the sure thing. The sure thing for Marty was Marty. Survival depended on the quantum ligature of attitude and style. His conjunction of skill and daring was acknowledged by the fans and the bookies. Times Square after the war was fierce and vibrant and the forms of entertainment were arabesque and lurid and fantastical. Marty vowed to be the greatest in the world.

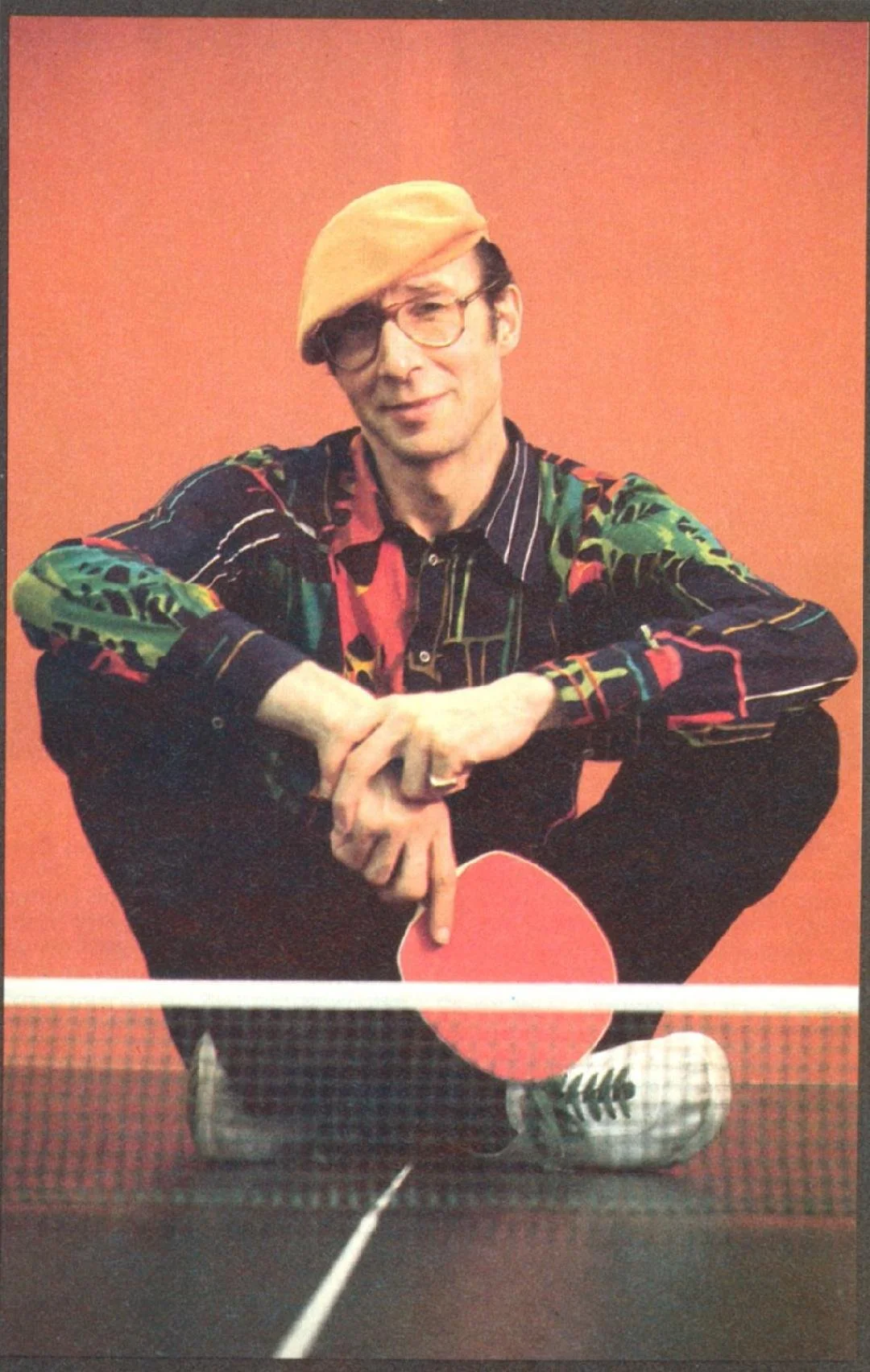

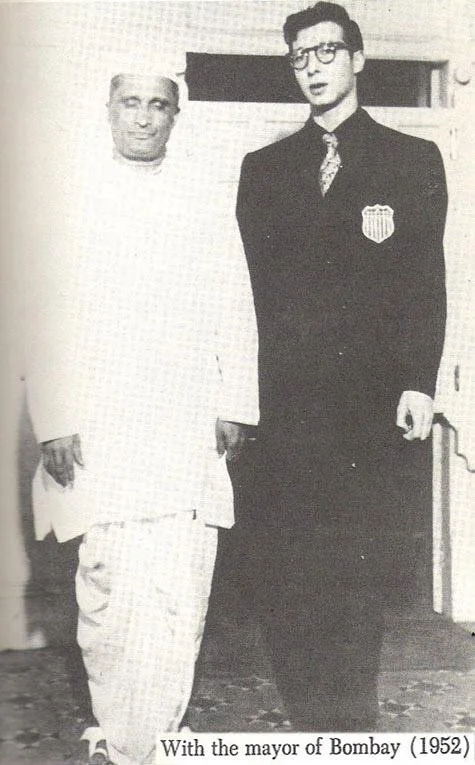

He began playing professionally and won several US tournament titles. At a time when his peers chose college, Marty was off competing for the World Championship, traipsing Scandinavia, North Africa, Brazil. He fostered the reputation of a dandy maverick, and played before the Maharajah in Bombay and the Pope in Rome. The British press called him the Walter Mitty of table tennis and he was a sports hero in Free China. Worldwide he gained the nickname “The Needle,” and fitted himself in Borsalino hats and Kiton suits, bespoke tailoring from Savile Row. He could use a shoe, beer bottle or trashcan lid for a ping-pong racket; he could return a serve behind his back, through his legs or with his heel, and introduce six balls on the table at once.

Marty never won the World Championship. He lost in 1948 and the next year was suspended from professional competition. The Money Player had been living the epicurean's life and on tour spent lavishly on hotel suites, the best duds, the finest nosh. Naturally he charged it all to the tournament sponsors: The Needle was the big show and drew the biggest crowds and so bet the odds they had no choice but to pay. The Table Tennis Association didn't see it like that and refused to foot the teen knave's bill, and banished Marty from the U.S. Team.

Instead of returning to New York, Marty roved the Far East playing exhibition matches on American military bases. The venture was a guise. There was a riotous gambling subculture in post-war Indochina and it offered Marty a stage to dance the dance he had spent his early years crafting on the Flamboyant Floodway. He played money matches in the swanky parlors and gaming halls of Manila, Tai Pei, and Saigon, bankrolled by Philippine industrialists and the Vietnamese jet set. He found side action on local black markets, exchanging French perfume, ballpoint pens, military scrip, women's stockings, foreign currency.

In the 1960s Marty bought a joint on the Upper West Side, “the city’s last table tennis academy, which is built into the side of a hill under a lunch counter and movie lobby at Ninety-sixth Street and Broadway.” For twenty years Reisman’s Table Tennis Club hosted cosmopolites and deadbeats. The Marquise de St. Cyr played in her mink coat and Tretorns against drool-lipped net-huggers; hepcats played speed chess with literary critics; Kokomo the chimp worked on his backhand stroke; and neighborhood kids hung around supplicating lessons from the Master, who ran the place as a debonair showman in Kangol cap and merino wool turtleneck. Stories about Reisman's appeared in the Village Voice and The New Yorker. When Reisman's closed in the 1980s, Marty bought a chain of Chinese restaurants and made and lost three or four fortunes on the stock market.

At sixty-eight years old, the veteran hardbat played the reigning United States Champion in the longest money match in table tennis history. The game lasted three and half hours and Marty was given 4 points, one point for each decade in age he outnumbered his opponent. Marty lost by a smidge in the final round. The $10,000, like the World Championship, was a win for the history books.

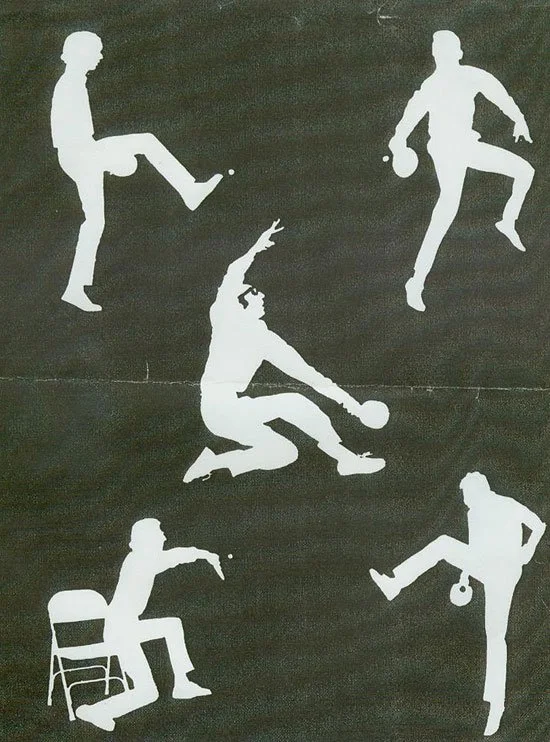

After the bookshop, I got a job as a double-decker bus tour guide, the best job in New York if one has to work. Up top the bus for the Night Loop, I had the chance to tell stories about Marty as we departed West 47th St. and 8th Avenue and soon passed the site of the old Madison Square Garden. When the Harlem Globetrotters played MSG, Marty and his colleague Doug Cartland performed a half-time acrobatic table tennis act, including frying pans as paddles to the tune of “Mary Had a Little Lamb,” and Marty causing the ping-pong ball to split a cigarette in half with one blammo stroke, his lifelong classic showstopper. The anecdotes provided a nice turn when the tour bus made the right east into the bright spectaculazium of old Broadway.

One day Marty called me while running errands about town. He had just got off the First Avenue city bus, where he had been approached by a tourist couple. “Are you the Money Player?” Turns out they had taken my Night Loop. “Why yes I am,” Marty answered.

New York City had rarely mourned a guy as born of its turf as Marty when the ping pong hustler died in 2012. See the noir baronial dash captured in a scene from Real Housewives:

by Andy McCarthy