Turpentine Monkeys

The 1939 social conscience drama Boy Slaves is the sole film directed by one P.J. Wolfson, which is a great shame given the film’s visual and dramatic virtues, but also grants it a little of the evocative might-have-been status of a Carnival of Souls or a Night of the Hunter. It’s not as remarkable as those – it pilfers too much from earlier Warner films like Wild Boys of the Road and The Mayor of Hell to have the same sui generis quality – but it has its own strangeness, and mystery. Since Wolfson was a producer at RKO, and relatively young, and his film displays self-evident skill amongst its more naïve moments, why didn’t he direct more movies? Perhaps he just didn’t enjoy the job.

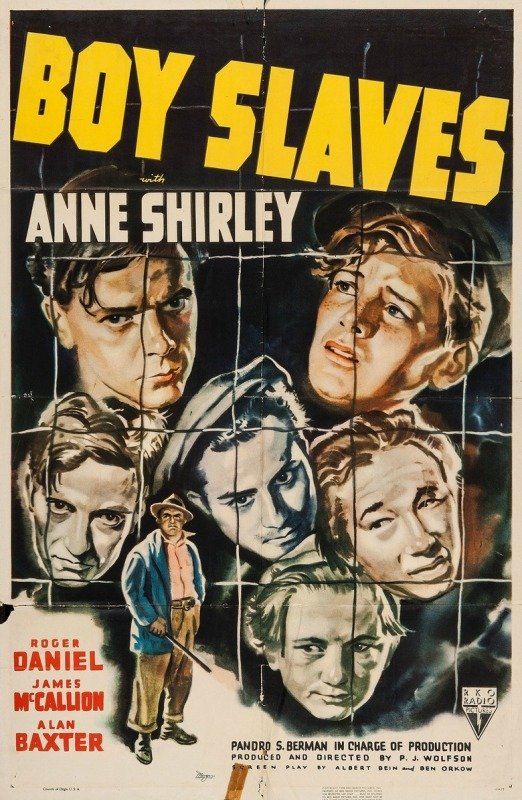

Young hero Jesse (Roger Daniel, who made a short career out of starring in this kind of melo (a whole juvie sub-genre: who knew?) runs away from home to save his mother the strain of supporting him, and falls in with (is mugged by, then inducted into) a gang of grotesque, aggressive homeless kids. Even by the standards of the Dead End Kids/East Side Kids/Bowery Boys, this is a remarkable crowd of miniature plug-uglies. Perhaps the advantages of casting adults with slightly stunted bodies in juvenile roles encouraged Wolfson’s apparent penchant for the physiognomically outré, but at any rate we have some spectacularly baroque facial architecture to admire here. Rococo, even.

One kid is either mixed-race or has some kind of genetic quirk which might be called “Deliverance syndrome.” All the kids are good actors in the forceful, slangy, yammerings manner considered appropriate for these kind of vehicles. There’s a black kid, who is one of the few who can sort of read: there are jokes about his ill-educated mind (“all men are cremated equal,” he reads aloud) but not more than with any of the other belligerent delinquents.

Incredibly, this squad of rascals are the heroes, not the villains – an early scene shows them violently robbing a rich kid of his pony-and-trap, and the Fauntleroy-type is shamefully typed as an effeminate mummy’s boy. But then they run afoul of the local law, and come up against bigger bad guys.

Indentured into the service or turpentine farmer Charles Lane, the whole tribe are forced to climb trees and peel bark, at jeopardy to life and limb; are fed disgusting stale muck; are tricked into debt at the company store; are paid in company script rather than cash. They seem set to spend their lives as, well, boy slaves (and then presumably adult slaves since the trap seems limitless in scope). Their childish attempts to break out or force changes in their treatment earn them beatings and loss of privileges and further debts. In the decidedly weird way of the prison drama, and particularly the women-in-prison film, we are invited to be horrified and somewhat titillated at the same time. I was reminded of the moment in Blazing Saddles when an old lady, beaten mercilessly by two ruffians, appeals directly to the camera: “Have you ever seen such brutality?”

Wolfson enlivens the basic sadism with crazed whip-pans and hallucinogenic subjective effects, as when the world spins, out of focus to represent the delirium of a starved boy up a tree. When Jessie attempts to escape through the forest at night, the slashed-up trees assume the countenance of feline demi-gods, a bit of Disney Snow White peculiarity that lifts the movie out of its own genre and up to Planet Psychotronic.

Wolfson slathers sentimental music on the emotional bits in a misguided attempt to evoke sympathy which rather smothers it, but as in the best of these things he creates enough genuine discomfort for the intended uplift of the happy ending to fall broken in pieces. Punishing the turp king for his child exploitation, a kindly judge remands our heroes, those that still survive (!) to “the state farm,” which incredibly is supposed to sound reassuring, but of course chills us to the marrow. Too bad Wolfson couldn’t have made a sequel in which our underage perps get mistreated even more, but in a sense he’s already made it just by having those words spoken.

No good can come of this.

by David Cairns