Places Are People: When the Setting is Ready for Its Close-Up

Cinema’s misspent childhood years in late-Victorian fairgrounds are followed by a grimy adolescence in Edwardian nickelodeon parlors. The medium, which finally comes of age amid gaudy palaces built in its honor, morphs many times. However, All Talking Pictures are the final death knell for the Victorian standard, belching from the screen a thousand inbred tongues that invade the ear willy-nilly. They remind us that Victoria Regina breathed her last in January of 1901, and with her passing Naturalism sheds decorum, taste, chivalry, good table manners.

Cinema grew from amusement parks, fairs, shows, an "attraction" for the rubes. And, like calling to like, the movies still nurture a fascination for such places of low pleasure.

As he shot Touch of Evil in and around Los Angeles' Venice Beach on a handful of nights in the early spring of 1957, Orson Welles would bashfully drape those trashy, less cinematic elements of the Mediterranean counterfeit before him in a voguish noir frock coat; one that would, at once, revel in the inherent ghastliness of such a place while concealing its full absurdity from eyes that would never be able to handle the contradiction.

Some years later, fate would conspire to choose Curtis Harrington, a cross-dressing Poe fanatic, to fully capture “The Slum by the Sea” with all its ravaged whimsy set against the lyric humiliation of once-ostentatious digs and the ruined face of spent oil wealth. Singularly unembarrassed by what he saw, Harrington gave audiences a Venice Beach that Welles would not: the sun-dappled occult, the queer, the criminal; a true, flophouse-ridden glory bathed in the endless California sunlight.

Night Tide (1961) assembles a distinguished skid row where underworld docents by the dozen — murderers, perverts, soothsayers and sea witches — pop into being with dazzling efficiency. Picture one thousand elves rising with glee to the same, single-minded curatorial task and you'll have a sense of what is involved here. In other words, as a demiurgic force, Harrington does not emerge from nothingness. After two decades fruitlessly bashing his head against the avant-garde wall, our schlockmeister arriviste goes Hollywood — that is, any imaginable “Hollywood” rude enough to splotch him with flat soda or leave him smelling of hot gravel and exhaust fumes.

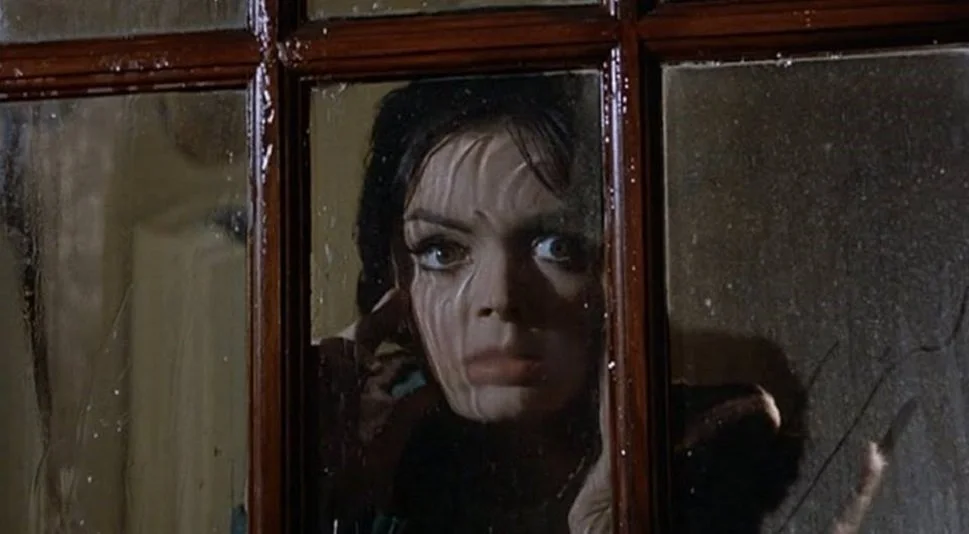

With its hinky cast — nonfictional witch, Marjorie Cameron; erstwhile muse to surrealist filmmaker Jean Cocteau, the undersung Babette who usually appears en travesti; and lecherous, booze-addled, fresh-faced Hollywood castoff Dennis Hopper — Night Tide invades the drive-in. A tarot reading at the film’s heart gives Marjorie Eaton her time to shine, traipsing into nickel-and-dime divination from her former life as a painter of Navajo religious ceremonies. Linda Lawson might have issued from an etching by Odilon Redon, with her raven locks and spiritual eyes, our resident sideshow mermaid. Not surprisingly and despite such gentle segues, the film itself traveled a rocky road from festivals to paying venues.

Despite the film’s scant $50,000 budget and somewhat dubious standing (after all, this was the director’s first attempt at feature filmmaking), Harrington captivates well-established eminences like cinematographer Floyd Crosby (Tabu) and composer David Raksin (Laura). Their contributions are keyed with great sensitivity to the film’s teasing invitations: “Do you want to live on a black and white Venice Beach boardwalk, have breakfast with a hot sailor and a hotter mermaid, hang with an old drunk captain and listen to the strange tales behind his morbid souvenirs?” It’s worth mentioning that Truman Capote, after catching a Times Square screening, adored Night Tide. We won’t ask what he was up to in a grind-house theater, but whatever it may have been, Mr. Capote encountered the movie in its ideal environment: equal parts sub-rosa poetry and grime.

Night Tide had spent three years languishing in the can when distributor Roger Corman smuggled the unlikely masterwork into public consciousness, another of his now legendary mitzvahs to art. And the sleazy-sounding double bills that resulted also unleashed an aberrant wonder: the movie’s compact leading man, a force previously held captive by the studio system — looking, here, like some homunculus refugee from the Fifties USA. Dennis Hopper, in his first starring role, would later recall that it represented his first “aesthetic impact” on film since his earlier appearances in more mainstream productions such as Rebel Without a Cause and Giant had denied him meaningful outlets for collaboration.

It’s the presence of its featured players — certainly not their star power — that lends the film its haunting and enduring legacy, and elevates the term “cult classic” to its rightful place in the pantheon of cinema. But I argue that Night Tide remains outside these exclusive parameters — upholding an elsewhere-ness that defies commercial, if not strictly canonical, logic. Curtis Harrington’s feature film debut escapes taxonomy, typology or genre — gets away — fueling itself on acts of solidarity instead. If Hopper contributes his dreamy aura, then Corman rescues the seemingly doomed project by re-negotiating the terms of a defaulted loan to the film lab company that was preventing the film’s initial release. His generous risk birthed a movie monument that would add Harrington’s name to a growing collection of talent midwifed by the lowbrow visionary responsible for nursing the auteurs of post-war American cinema.

Raymond Durgnat, who finally sees Night Tide in 1967, approves it for “connoisseurs of the offbeat” while neglecting the creator’s true offbeat depths. Scratching a eulogy in longhand for his 2007 funeral, cult icon Barbara Steele reminds us that Harrington owned a pair of Judy Garland’s emerald slippers, slept among the mummified bats that decorated his bedroom walls and amassed an eclectic array of human specimens: “Marlene Dietrich, Gore Vidal, Russian alchemists, holistic healers from Normandy, witches from Wales, mimes from Paris, and beautiful men from everywhere.” (His squalid dinner parties summon imperial decadence, scenes out of Hogarth.) Steele ends with her fond recollection that: “Once you were inside his charmed circle you would never be banished, it was such a delightful place to be, you wouldn’t want to escape… and you loved him with all your heart.” Well, doesn’t that selfsame pas de deux perfectly delineate Night Tide’s inner world: unwonted inhabitants and mainstream audience caught in one gently swirling embrace? Here, celluloid joins the dusky beachfront ruin that the Venice Beach boardwalk had become with expressionist visions of a churning sea.

By the Sixties new waves were crashing everywhere. The frisson of La Nouvelle Vague should be understood in a tempest of plurality that shook Hollywood, whose producers, trained in the relative stasis of studio-system majesty, were being tossed willy-nilly on the backs of Italian, British and German breakers. And, emerging from this unpredicted deluge of international currents, spawning endlessly exploitive countercurrents, came Barbara Steele, a castaway or, as she herself puts it, “an unwilling immigrant” in the heart of Hollywood-land where she unhappily resides today. More than six decades have passed since she played an avenging witch in Black Sunday, but no matter how stubbornly Steele refuses to claim her title as Italy’s reigning Scream Queen, the aura of dry ice and stage blood lingers in the cinematic unconscious, trailing her in gory wreaths. She remains a prisoner of her proudest memory, Fellini’s Otto e Mezzo, compared to which her genre horror films — The Long Hair of Death, An Angel for Satan, Terror Creatures from Beyond the Grave — essentially amount to the gothic flop house of cinema history. Or so the self-tormenting diva chooses to believe.

The Italians would dragoon her immaculately virgin-white screen image, from England’s ashen shores to their own sun-kissed and suggestive peninsula. From whence Steele’s stolen likeness, now the ultimate (cosmic) femme fatale, would commence irradiating Southern peasants with previously unknown iconographic power. Steele, in other words, weaponized what Mario Bava and Riccardo Freda had bestowed upon her as the greatest, and most acquisitive, directors of Italian genre horror: that exalted say-so reserved for goddesses. Black Sunday will never be classified as “New Wave”, nor will Georges Franju’s Eyes Without a Face. Nor will any category of filmmaking moored to genre (whether it be horror, science-fiction or le cinéma fantastique) gain admittance to the brick-and-mortar Canon, whose location and visiting hours remain the jealously guarded secrets of custodial film critters. And while I don’t begrudge Cahiers du Cinéma its fun concocting nomenclature, I do prefer celebrating unnamable dissonance — or, to put it another way, films finding themselves as they’re being filmed.

Robert Altman in the 70s allows this to happen. Monte Hellman, too, resists the embalmed repose of those big, cumbersome productions helmed by flunkies to a gilded studio system, in which directors essentially serve as ghost captains of a sunken barge. I’ll end my little meditation, appropriately enough, on Jean Epstein’s glorious cinematic ode to “the storm-tamer”.

Le Tempestaire (1947) is almost enough to shake my devout atheism. Is this a film, an experiment in sonic plasticity, a séance, or some elaborate form of dialectical math — one plus one equals three? Full disclosure: painters, who speak monosyllabic caveman lingo to describe the dynamic force-field-like tension of the picture plane, raised me. Add a “blue” to a “red” and you may get “space.” “Push and pull,” the muscular rhythms resulting from colors that vie for spatial dominance. And Jean Epstein’s penultimate film mirrors the same painterly axiom of sublimated emotion; only here, the dialectic involves sonic and visual elements. Twinned movements. The sea heaves in slow motion. Throwing off well-spoken shrieks. An instrument more alive than the Theremin matches octave for brooding octave my growing apprehension as nature’s working parts are isolated and reshuffled. Everything — sound, image, time itself — decelerates. (Think E.J. Marey brought into a fully cinematic register of experience, without pause or rupture and complete with synchronous, fully dissected hubbub.) Until the grammar, syntax, and disputations of a cresting wave become movie stars. Who knows why this soundtrack qualifies as something far greater than anguished dramaturgy? The results are easier to grasp formally than ‘spiritually’.

Le Tempestaire doesn’t merely resemble an undulating graveyard — or evoke metaphorical lost souls wailing in the storm. Epstein’s plastic means are so perfectly allied that formalism itself buckles. As the music troubles the imagery and the imagery brakes to a nigh standstill, we suddenly find ourselves engulfed by spirits.

by Daniel Riccuito