Slap and Tickle

Val Guest was a rare sort of British auteur, both for his beret-wearing artiste pose and for the way his eyes strayed to the south and the west, across channel and ocean, rather than settling for insular influences. European sexual license clearly appealed to him, and his mature face is dotted with surprise nipples which come out of left field and belong to lovely actresses you don't expect to denude: Janet Munro, Claire Bloom, Diane Cilento. But then he took the plunge into full softcore and the result could easily induce rigidity in both sexes. Though Guest petulantly argued that, had it been a French film, Confessions of a Window Cleaner (1974 ) would have been acclaimed as a spicy masterpiece of eroticism, exposure to it and The Au Pair Girls (1972) might easily cause ova to implode, spermatozoa to swim upstream, back into the balls, bent on selfspermicide. Perhaps comparison could be made to Paul Verhoeven's Turkish Delight (1973), whose hero's sexual adventurism seems as joyless, though less anxious, than Robin Askwith's licentious activities up a ladder. When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth (1970), a nudist film in caveman drag, does not succeed in effectively combining titillation with tyrannosaurs.

Guest's interest in American cinema seems to focus on the fast-talking newspaperman genre, which he transplants effectively into sci-fi disaster The Day the Earth Caught Fire (1961), and in the fact-talking comedy of the Marx Brothers. Guest had a long apprenticeship in the 1930s as screenwriter, and here he tried to import Marxian zip and cheek to a whole slew of vehicles for comedians, mainly from the music halls. Well, the Marxes came from vaudeville, so why not?

Item: the Crazy Gang. Three double acts in trandem, piled into makeshift vehicles whose zaniness makes them sound more fun than they in fact are. Gasbags (1941), for instance, sets the gang adrift on a barrage balloon, landing in Germany where they're interned in a comedy concentration camp full of defective Hitler lookalikes — they escape via a captured Nazi digging machine, a Teutonic version of Edgar Rice Burroughs' "iron mole."

Six comedians is clearly too many to cope with, and they're a fantastically indistinguishable mob. The two Scottish ones, Charlie Naughton and Jimmy Gold, can do pratfalls — too bad nobody in British films seemed to know how to shoot slapstick. Jimmy Nervo and Teddy Knox are Jewish stereotypes (Guest was Jewish too), and Bud Flanagan and Chesney Allen take care of the singing. But other than that, they all run about like maniacs and make bad puns. They seem to find themselves, and each other, amusing (the Marxes never did — perhaps Groucho gets some secret satisfaction out of his manic wordplay, but he doesn't really let on).

Guest typically worked in a team of three on these things, and the other names usually included some combination of Val Valentine, Marriott Edgar, and J.O.C. Orton. They also penned films for music hall shortarse comedian Arthur Askey ("! thangew!") a sort of cheeky chappie in hornrimmed glasses, like Harold Lloyd's parasitic twin, and, perhaps most effectively, for Will Hay.

Hay was not just a comedian but a proper character actor, with an indelible screen character, somewhat derived at first from his admiration for W.C. Fields (he even imported America's William Beaudine who had helmed or anyhow refereed a Fields picture, as if this might help him capture the lightning in a bottle or at least whisky), but incorporating a uniquely British fussiness and fustiness. Unlike Fields, Hays embodied incompetent authority figures: teachers, lawyers, firemen, station masters. It's never certain how satirical the intention is: are we encouraging a healthy disrespect for those in charge, or is the joke simply one of absurdity? As George Orwell wrote of P.G. Wodehouse's Jeeves & Wooster, the comedy arose from the absurdity of a servant being infinitely smarter than his master. It seems subversive but it isn't really.

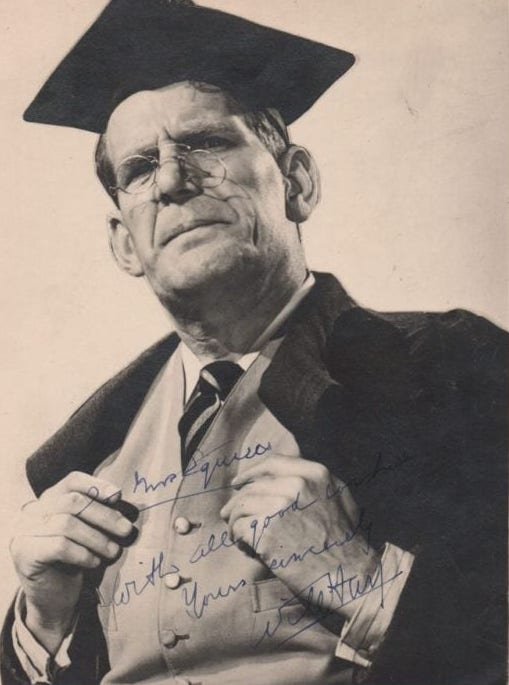

Well, maybe a little. Hay, in pince-nez and a bald cap with combover and floppy fringe, is a figure constantly aspiring to a dignity of office he can never attain. Hence all that shouting: joined by Moore Marriott (fake old man with missing teeth and Irish beard) and Graham Moffatt (actual fat youth), for a while Hay became the fulcrum of a team which had one foot in Marxian crosstalk, the other in Fieldsian character study. Hay (usually playing someone called Ben), an intellectually shambolic loser, is hyped into a frenzy by the manic oldtimer (usually Harbottle) and the phlegmatic youth (always Albert), and they get just as annoyed with him. Keep a finger on the volume control.

Often directed by a stray Frenchman, Marcel Varnel, whose work has a surprising smoothness and elegance which seems almost counterproductive for this noisy rattletrap farce, the films often entail Scooby Doo fake hauntings unmasked as the work of smugglers, robbers, or fifth columnists once the war got going. Or Hay has to make good at a new school, where his gullibility to every vicious schoolboy prank turns him into a sympathetic figure despite his profound ignorance and corruption.

Put upon by a pupil in Boys Will Be Boys (1935), Hay demands that the offender stands up. When he towers over Hay, he gets another, much smaller and totally innocent boy to stand up, and cuffs him across the head.

The films, in truth, are not as funny as esteemed precursors Marx and Fields, and the constant yammering can be wearisome, intensified by the weaknesses of 1930 sound recording, but there's a real sense of a British personality and attitude to life being captured, an alienated, askew and skeptical viewpoint not otherwise documented in film, theatre or literature of the time but which obviously spoke to the people who came to laugh. And, though one shouldn't underrate Hay's role in creating his own character, some of this mordant feeling is certainly Guest's. He didn't much like heroes. Things, it is clear, are terrible; those in charge are crooked and imbecilic; but it'll all turn out all right in the end.

It didn't, of course (Hay broke up the act and died young, as did Marriott, who never attained the age he impersonated, and Moffatt, who retired to run a pub and have a heart attack). It never does. But England goes on dreaming. As Flanagan and Allen sang, Pavement is our pillow / Without a sheet we'll lay / Underneath the arches / We dream our dreams away.

by David Cairns