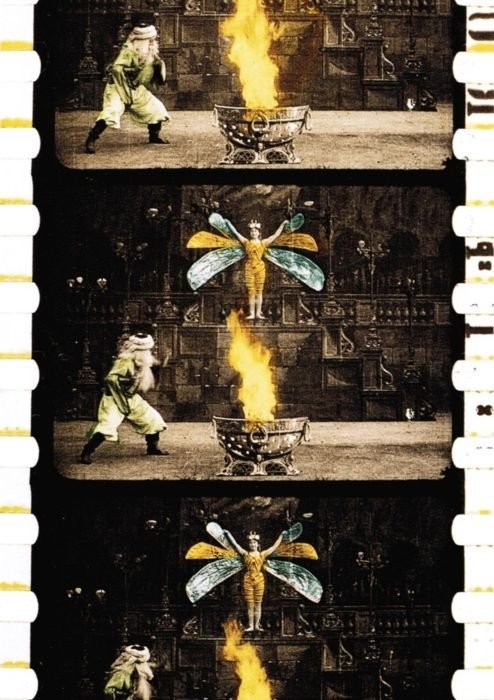

Méliès and “The Divisible Man”

Georges Méliès reimagined physics. And, in the process, put to shame Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man. Renaissance empiricism was, momentarily, kaput. If one had a mind to catalogue Méliès’ ingenious transformations, then a plausible title might be “The Divisible Man”: detachable head, multiplying detachable head, expanding detachable head, the head as heavenly body, the body smithereened and reassembled… But of course a modern, tech-based art form like cinema makes “originality” itself suspect. Méliès cannibalized the works of Verne, H.G. Wells and Poe, or poached from their hunting grounds, without worrying in the least about copyright, and documented the same sorts of fantastic voyages to the moon, the south pole and the ocean floor, by outsize, inhabited artillery shell, by balloon or airship, rocket-train, or whatever fantastical machine could be cobbled together in his greenhouse studio. While the literary fantasists were somewhat concerned with credibility, with the science part of science fiction, the Frenchman with the upside-down head (bald top, hairy underside) focussed purely on visual possibilities: an idea was only any good if it gave you an IMAGE.

A Genesis Out of Light

Would it be preposterous to argue that movies are essentially projected books, books made out of light? Even weirder, let’s entertain the idea that Jules Verne’s science-fiction imagery, which finds itself transfigured early in the development of cinema, is not alone: the audience — you, me and everyone watching — dissolves into moving illustrations. “Motion pictures”. A horrifying thought if we “foolishly” believe that our three-dimensional selves could squish, flatten (and like it!).

Dating at least as far back as Georges Méliès, the cinema of bodily transformation did not necessarily equate with “horror” per se. The horror film was eventually codified as genre from the cinema of bizarre attractions exemplified by Lon Chaney, master of grotesque makeups and bodily contortions, but in the early cinema it was standard procedure to have one's detached head inflated to fill the room (The Man with the India Rubber Head) or multiplied into a row of bodiless noggins, singing or rather mouthing in harmony (The Four Troublesome Heads). Then came Nosferatu, preordained to shimmer on-screen. Vampires, immortals of the night, slain by sunlight, rose out their tombs in the movie theaters of the 1920s and never returned. They sit next to us in the dark, having ceded the power of hypnotism to the glowing screen itself. Photochemical vagaries invariably allow movie darkness to behave in uncanny ways; as if the physical properties of film followed no rules, and thus invited us to accept its essential anarchy without question. Before us, the darkness GLOWS.

Tinted Wraith

Magic mirrors; celestial mandalas; a sinuous puppet rising like a malign concertina from a well.

Segundo de Chomόn is such a significant player in film history that it’d be possible to fill an article with his achievements without even describing the films he made at all – special effects artist, photographer, director, he refined color cinematography, combined live action with animation, and built the first camera dolly. The hundreds of films he worked on span the full range of early cinema, from one-shot travelogues in 1903 to Abel Gance’s Napoleon in 1927, for which he devised special effects, he was in the forefront of movie magic his entire life, but the films he’s chiefly remembered for are in the Méliès vein.