“I’ve Got Money Singing in My Brain!”: DECOY (1946)

It’s just one cruel joke after another. An executed man is brought back to life, only to be shot dead minutes later. A noble doctor who has devoted his life to serving the poor is seduced and duped by the world’s most avaricious woman, who shrewdly points out, “You like to smell the perfume I use. This perfume costs $75 a bottle.” Her partner in crime enjoys gloating over her victims, only to become one of them when she stomps on the gas pedal while he changes a flat tire. As she lies dying, the woman asks the cop who has hounded but reluctantly admires her to “come down to my level, just once”; then as he finally succumbs and leans in for a kiss, she laughs in his face. For a finale, the box of loot she died for turns out to be filled with worthless scrap-paper. It’s the decoy; so is she; and so is money, the love-substitute, sex-substitute, life-substitute that makes this grubby world go round.

Cliff Edwards: He Did It With His Little Ukulele

Cliff Edwards is better known as Ukulele Ike, and best known as Jiminy Cricket. But cast an eye down his movie credits, from 1929 through 1965, and the names of his characters form a jazzy found poem of monikers. He was Froggy, Foggy, Owly, Pooch, Snipe, Bumpy, Screwy, Louie, Stew, Dude, Rooney, Snoopy, Pinky, Sleepy, Shorty, Runty, Speed, Tip, Tips, Hogie, Handy, Happy, Harmony, Nescopeck, Minstrel Joe, Banjo Page, Bones Malloy, and—my personal favorite—Squid Watkins. This slang menagerie says a lot about the off-beat appeal of one of the 20th century’s most unique and endearingly oddball talents.

Clifton A. Edwards was born in 1895 in Hannibal, Missouri, hometown of that other great American master of the nom de plume, Mark Twain. He grew up poor, selling newspapers on the street. A natural performer, he ran away and by 16 was singing in saloons and carnivals in St. Louis, where he picked up his nom de uke courtesy of a waiter who couldn’t remember his real name and dubbed him Ukulele Ike. He had adopted the tiny Hawaiian guitar and the kazoo so that he could accompany himself as an itinerant entertainer. He rose through vaudeville, teaming up with the comedian and eccentric dancer Joe Frisco, then achieved his first great success on Broadway in the 1924 Gershwin show Lady Be Good, starring Fred and Adele Astaire, in which Edwards introduced the hit “Fascinatin’ Rhythm.”

His trademark instrument, with its comical size and association with 1920s hot-cha frivolity, suited Edwards’ vaudevillian persona, but may have tended to obscure his serious gifts as a musician. He does get credit for being among the very first white artists who can truly be called a jazz singer; he knew how to swing a song and how to elaborate on it by scatting and imitating instruments—in his case, with wild kazoo-like choruses, bluesy muted-trumpet growls, and uninhibited yowls suggestive of a cat on a back fence. But Edwards could also croon a straightforward love song in a high yet natural tenor—pure, warm and unadorned—that is far from the ludicrously effeminate falsetto affected by many twenties crooners, or the limp, wan stylings of Rudy Vallee. He could even redeem sentimental pablum with his simple and tender delivery. Though he lacked suave looks or a husky, sexy voice like Bing Crosby’s, he brought vulnerability and honesty to love songs without ever slipping into the maudlin.

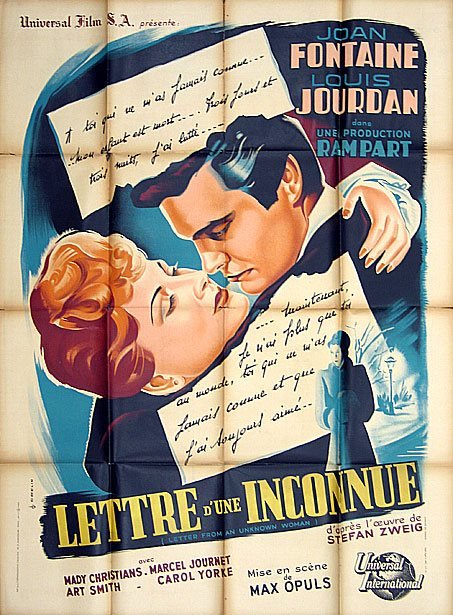

Women of Letters

The first time I saw Letter from an Unknown Woman, I admired its craft and atmosphere but hated the story, about a woman who wastes her life in abject devotion to an unworthy man. A decade later I saw the film again, and found it as different as the heroine finds her beloved after ten years. Now it was not a tale of unrequited love, but a devastating anatomy of the illusions that lie at the heart of romance and even at the heart of our identities. The self-sacrificing woman and the self-absorbed cad both throw their lives away on false ideals, but their lives still have weight and beauty—so even do their ideals.

Mae Clarke: An Honest Woman

There is a certain look of wary, contained bitterness that you see on women’s faces in movies from the early thirties. Their eyes become veiled; the women seem to retreat inside themselves defensively, tasting memories of hurt and humiliation, of men who made them feel dirty and how they had to keep on smiling and flirting so they could pay the rent on their drab hall rooms and buy their automat coffee. It’s the look of the chorus girl who has learned to protect herself by shutting down the gates, even while wiggling in her scanties. Barbara Stanwyck carried it throughout her long career, like an eternally livid scar; “bubbly” Joan Blondell wore it quietly; and in Waterloo Bridge (1931) it’s branded on the face of Stanwyck’s one-time roommate, Mae Clarke.

Waterloo Bridge opens with a shorthand summation of a chorus girl’s life. It’s the all-hands-on-deck finale of a fluffy musical revue on the last night of its run. The camera pans past the interchangeable faces of the chorines in their platinum wigs and sparkly tricorn hats, and comes to rest on Mae Clarke, as Myra Deauville. She throws up her arms and gives an open-mouthed laugh, then lapses into exhausted boredom, then switches on the faux exuberance again, then yawns. Throughout the film she keeps doing this: putting on her game “Hello, big boy” act and then flinging it aside with furious disgust. Director James Whale doesn’t bother with transitions, but conveys the whiplashing ups and downs of his heroine’s life through blunt cuts. We see her backstage in her bra, receiving a white fox stole from an admirer; in the next scene, out of work for two years, she’s wearing the stole low around her décolletage, standing outside the theater with a fellow hooker looking for pickups. (The setting is World War I, but when Myra says hopefully, “I’ll get a job soon,” 1931 audiences must have foreseen the worst.)

Spotting a prospective john, the friend primps and smiles flirtatiously, while Myra turns on him with a defiant yet seductive scowl; a sullen, defensive stance that she assumes throughout the film. She suffers from incurable decency, which becomes a scalding torment when she meets an innocent young doughboy who has no idea that she’s a prostitute. She brings Roy (Kent Douglass) to her flat, intending to pluck him for the back rent she needs to satisfy her sour-faced landlady. But it’s too easy: when the sweet, boyish soldier pleads with her to accept the money, she abruptly drops the good-natured frankness she’s been charming him with and turns hard and caustic, hating him because she hates herself for tricking him. She’s so stung with hurt pride that she has to lash out and hurt someone else. Preparing to go out on the streets after sending him away, she stares at her hard face in the mirror, dabbing make-up on the rigid mask that barely conceals the tired, angry sadness beneath.

Waterloo Bridge is the only film that reveals the breadth of Mae Clarke’s talent. In other movies she played nice, open-faced girls or mean, petulant golddiggers. As Myra she is a kaleidoscope of confused emotions. Her best scene comes when Roy tells her he loves her: she turns away, hunched as though against a cold rain, her eyes narrow and tense. This is the final insult from life: for her dream guy to come along too late, when she feels unworthy of him. Leaving, he kisses her hand, and reacting to this tribute she passes through exaltation, anxiety, and rage—growling as she forces herself to cast it aside. She’s too honest to grab the expedient of letting a man make “an honest woman” out of her. But we know she loves him, because in the next scene she’s trying to knit him a pair of socks, sitting at the breakfast table with her hair piled on her head, a cigarette planted in her mouth, mangling the stitches.

The worst is yet to come: well-meaning oblivious Roy tricks her into visiting his posh family in the country. They’re kind and welcoming in that self-satisfied upper-class way bound to cause excruciating discomfort in someone like Myra. Roy’s mother (Enid Bennett) is polite, complacent and deadly. Watching her sweetly confide to Myra that she doesn’t want her son to marry a chorus girl, but that she knows she has nothing to fear from such a “fine” person, is almost unbearably painful. Reduced to abject guilt, Myra confesses her true profession and pitifully sobs, “I just wantcha to know, I could’ve married him…”

The Invisible Border: “The Man Between”

“Wickedness,” Oscar Wilde wrote, “Is a myth invented by good people to account for the curious attractiveness of others.” Both The Third Man (1949) and The Man Between (1953), a film that suffers from perennial unfavorable comparison to Carol Reed’s earlier masterpiece, revolve around men whose attractiveness is inseparable from their amorality. But while Grahame Greene’s script for The Third Man ultimately strips away Harry Lime’s glamour, reducing him to a scurrying sewer-rat and a suicidal nihilist, The Man Between embraces the tragic romanticism of its more ambiguous anti-hero.

Glad Rags: Fashion and the Great Depression

Some years ago, in a breathtaking lapse of taste, The New Yorker published a fashion spread that aped iconic photographs of Dust Bowl migrants. I was as appalled as the next right-thinking person by the pouting models in $400 distressed cardigans pretending to thumb rides along desert highways. But if the charge is infatuation with the aesthetics of the Great Depression, I am guilty, guilty, guilty. Throw me in the clink—just so long as it resembles the hoosegow that Barbara Stanwyck saunters around in Ladies They Talk About (1932).

Why was everything, from automats to automobiles, from nightclubs to radios, from skyscrapers to bus stations, from cocktail shakers to the battered hats on homeless men, so elegant in the thirties? Why did bums back then look better than bankers today? Why are the movies and music, the clothes and every aspect of design from typefaces to elevator panels, so intoxicatingly stylish?

Fats Waller: Baby Elephant Patter

Was Fats Waller put on this earth to send up inane pop songs, or did Tin Pan Alley busy itself churning out an endless supply of vapid tunes just to feed his enormous appetite for ridicule? Either way, it wasn’t a bad deal: while he was irrepressible in his vocal shenanigans and merciless in his mockery of cornball lyrics, Waller also bestowed on assembly-line songs unwarranted beauty. His touch on the piano was like a hummingbird’s wings, like sunlight scattering on moving water. The great clown of jazz, Thomas “Fats” Waller belongs, with Oliver Hardy and Roscoe Arbuckle, to that brotherhood of fat men whose girth serves to counterpoint their buoyant grace and delicacy. His music is at once thundering, voluminous, and dainty, like the “baby elephant patter,” he invokes in “Your Feets Too Big,” or like one of Disney’s hippo ballerinas twirling on pointe.

Disturbing the Peace: Florence Turner

Florence Turner was a beautiful woman, with large dark eyes and a long, fine-boned face. She was also riotously funny. A parade of gorgeous comediennes have followed in her footsteps—Mabel Normand, Constance Talmadge, Anita Garvin, Carole Lombard, Lucille Ball, Judy Holliday et al.—yet they continue to be viewed as exceptions to some unwritten rule: that women aren’t funny, that only unattractive women are funny, that being funny makes women unattractive. Even Walter Kerr, one of the greatest writers on silent comedy, dismissed female comedians as being handicapped by the necessity that they be pretty. If beauty is a handicap in comedy, Buster Keaton should never have earned a single laugh.

In Daisy Doodad’s Dial (1914), Florence Turner blows a sustained silent raspberry at this whole uncomfortable issue. This one-reel British-made comedy centers around Daisy’s determination to enter and win a face-making contest. (Your dial is your map, your pan, your puss, in other words your face.) Practicing at breakfast with her husband, in a bus with two horrified male strangers, or in a police station—after she is arrested for disturbing the peace—she pulls the most hilarious and outrageous succession of faces I have ever seen. But the funniest thing of all is the way she alternates this array of grotesques with a subtle, dignified deadpan. One moment she’s a gargoyle, a ghoul, or a goofball; the next moment she’s an elegant lady, someone who might be painted by John Singer Sargent. Turner has absolute control over every muscle of her face, and her expressions are as readable as the morning newspaper, but also witty and pithy as aphorisms.

After seeing Daisy Doodad’s Dial as part of the BFI’s magnificent compilation “A Night at the Movies in 1914” (which also includes footage of the militant suffragist Emmeline Pankhurst being hustled out of Buckingham Palace by a pair of hulking bobbies), I understood why Buster Keaton had the inspiration to hire Florence Turner to play his mother in College (1928). It’s a wonderful bit of casting—though she was in fact only ten years older than he was. They look remarkably alike, and Turner matches Keaton’s stoic deadpan beautifully.

By 1928, however, she had been completely forgotten, and by the 1930s she would be doing bit parts and extra work. Known at the start of her career as “The Vitagraph Girl,” Turner is not to be confused with Florence Lawrence, “The Biograph Girl,” who is labeled by film histories as the first movie star. Turner was perhaps the second, and was celebrated as both a comedienne and a dramatic actress. In 1912, she was voted the most popular woman in the movies. A year later she left for Britain where she formed her own production company, Turner Films. (The move was attributed to the stifling effect of the Motion Picture Patents Company, which also drove many filmmakers to abandon the east coast for Hollywood.) In 1914, she was voted Britain’s most popular female film star. She also wrote and directed some of her films, including Daisy Doodad’s Dial. Tragically, it is one of only two survivors from her British productions.

Why her career began to fade as early as 1916 seems to be unexplained. She is virtually unknown today, though many of her Vitagraph films survive. The entry on Turner in Columbia University’s online Women Film Pioneers Project whets the appetite even more. For instance: “Possibly Turner’s most demanding role was the rejected lover in Jealousy (1911), a film now lost. Promoted by Vitagraph as ‘A Study in the Art of Dramatic Expression by Florence E. Turner,’ the film was a tour de force for the actress, as she was the sole performer on-screen for the entirety of Jealousy’s running time…Moving Picture World, in August 1911, stressed the centrality of performance to the effectiveness of the film: ‘[The actress] has the courage to let the truth be told in her countenance and movements. The audience gazes into the mystery of a human soul.’”

This sounds well worth seeing, but I’m not sure gazing into the mystery of a human soul would be as much fun as gazing into Florence Turner’s face at the end of Daisy Doodad’s Dial. In a marvelous dream sequence, Daisy lies tossing and turning in bed while a parade of her own ghostly images marches past, each pulling a different wild face. You might think the film will end with her chastened and newly demure, but instead it ends with her in close-up staring directly at the camera and pulling even more faces, defiantly distorting her handsome features with rubbery zeal. A hundred years later, her message is clear.

by Imogen Sara Smith

Three on a Match

The title and premise of Three on a Match suggest an ensemble film, but don’t be fooled. This is Ann Dvorak’s movie, and the finest showcase for her avid, feverish energy. She was twenty years old and blazing her way through her first year as a star, starting with her electrifying turn as Tony Camonte’s insatiable sister in Scarface. Slender and elegant, with a refined beauty, Dvorak always seemed to be looking for trouble. “Somehow the things that make other women happy leave me cold,” she says in Three on a Match, explaining the gnawing dissatisfaction that a devoted husband, a cherubic son and a life of luxury can’t assuage.

The other two on the match are Joan Blondell and Bette Davis, but they are stuck with tepid roles, and even Warren William (as Dvorak’s husband) is uncharacteristically virtuous and bland. All raw nerves and dangerous luster, Dvorak makes her haughty, self-immolating character not only more interesting but more sympathetic than the nice women who profit from her fall.

Seduced by a penniless playboy (Lyle Talbot, leaving his usual trail of slime) she shacks up with him in a hotel suite, neglecting her child, and slides rapidly from champagne parties to drug-addicted poverty. The movie really starts to get good when the debt-ridden Talbot kidnaps Dvorak’s son. In a noirish sequence, they all hole up in a squalid apartment, guarded by a trio of goons led by Humphrey Bogart, who nastily mocks Dvorak’s cocaine withdrawal. Three on a Match crystallizes her daredevil glamour, while also offering a brisk, punchy warning about what happens to girls who play with matches.

by Imogen Sara Smith