Frankie Darro: No Strings

He was the voice of Lampwick in Walt Disney’s Pinnochio (1940), the bad boy who gets turned into a donkey on Pleasure Island, maybe the most upsetting scene in any Disney cartoon. He was one of two actors inside Robbie the Robot in Forbidden Planet (1956), small enough to fit inside the costume. He played lots of jockeys and Dead End Kids and Bowery Boys, and he made scores of low-budget westerns. He was menaced by Boris Karloff in The Mad Genius (1931). He was a man in a leg cast hoisted up in his hospital bed in Blake Edwards’s The Perfect Furlough (1958) and he examined Cary Grant’s posterior in Edwards’s Operation Petticoat (1959). As an adorable, Jackie Coogan-like little boy, he got a laugh asking a woman to dance in Flesh and the Devil (1927) right before Greta Garbo waltzes away with John Gilbert. He was a son to Marie Dressler’s Tugboat Annie. On Red Skelton’s TV show in the 1950s, he did an old lady routine that routinely brought down the house. Frankie Darro had a long and varied career. And in 1933, in two films, Mayor of Hell and William Wellman’s Wild Boys of the Road, Darro is an actor with a capacity for greatness, if anyone had bothered to notice.

Annals of Censorship #1

Mr. J. L. Warner,

Warner Bros. Studios,

Burbank, California

Dear Mr. Warner:

We have read the final script of your production, WILD BOYS OF THE ROAD, and have given it very careful consideration. It seems to us that it contains several major problems to which some further consideration should be given both from the standpoint of the Code and censorship.

First we feel that the characterization of Aunt Carrie's residence as a house of prostitution is very questionable under the Code and dangerous with regard to official censorship. Consequently, it would be wise to change the nature of these scenes radically and indicate, if possible, that Aunt Carrie runs a speakeasy or that she is implicated in any other kind of a racket which might make her liable to arrest. If such a change were made, all the story necessities would be saved and, at the same time, a very dangerous situation would be avoided.

The Crowd Doesn’t Just Roar, It Thinks: Warner Bros.’ All Talking Revolution

“Iconic” is a gassy word for a masterwork of unquestioned approval. But it also describes compositions that actually resemble icons in their form and function, “stiff” by inviolate standards embodied in, say, Howard Hawks characters moving fluidly in and out of the frame. Whenever I watch William A. Wellman’s 1933 talkie Wild Boys of the Road, these standards—themselves rigid and unhelpful to understanding—fall away. An entire canonical order based on naturalism withers.

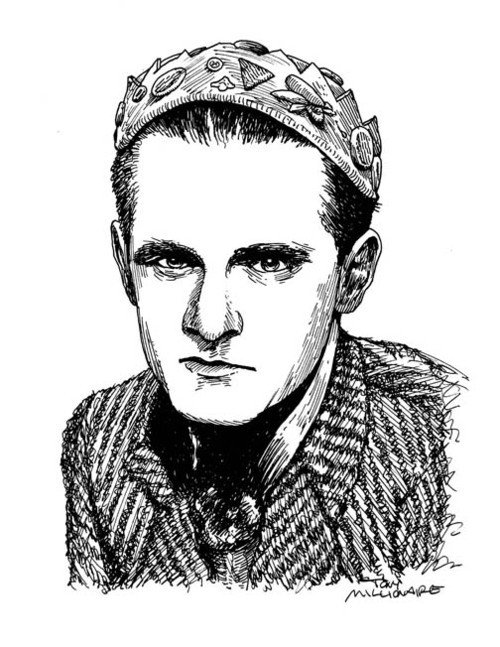

To summon reality vivid enough for the 1930s—during which 250,000 minors left home in hopeless pursuit of the job that wasn’t—Wellman inserts whispering quietude between explosions, cesuras that seem to last aeons. The film’s gestating silences dominate the rather intrusive New Deal evangelism imposed by executive order from the studio. Amid Warner Bros.’ ballyhooing of a freshly-minted American president, they were unconsciously embracing the wrecking-ball approach to a failed capitalist system. That is, when talkies dream, FDR don’t rate. However, Marxist revolution finds its American icon in Wild Boys’ sixteen-year-old actor Frankie Darro, whose cap becomes a rude little halo, a diminutive lad goaded into class war by a chance encounter with a homeless man.