The Future in Yellow

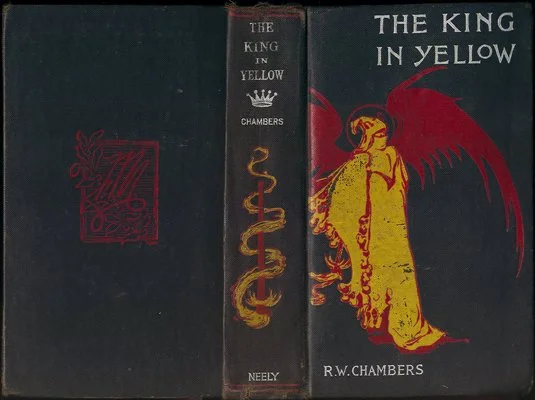

Robert Chambers published The King in Yellow in 1895, with some elements of SF, more of horror and fantasy, and a literate style that could pound most of his contemporaries into the ground.

A collection of two batches of loosely connected short stories, it is one of the most puzzling books ever produced. Though he went on to write best-selling historical romances (which I haven't read and, judging from most comments, wouldn't want to), Chambers apparently never again produced anything close to its quality. Despite making money at fiction and writing extensively on hunting, he remains an enigma.

"The King in Yellow" of the title is a fictional play the very reading of which can drive the reader mad. Through this and later works, Chambers was a major influence on H.P. Lovecraft, but he did not waste his time, as Lovecraft did, on mucus-slathered adjectives. The horror comes from character, superbly rendered detail – Chambers studied as a painter – and an uncanny ability to suggest rather than declaim. Most likely, he also provided the idea for the fearful drama that lurks in the background of Thomas Pynchon's The Crying of Lot 49.

Every story of The King in Yellow has something riveting about it, though in many the disparate parts are never fully explored or connected. Only the first four actually mention "The King in Yellow," and only obliquely, which makes it all the more astonishing that they became the model for much of 20th-century horror/fantasy.

It's hard to pinpoint what Chambers was up to, and this may be his greatest strength. "The Mask" and "The Yellow Sign" deal most directly with the virulent effects of reading "The King in Yellow," but it's "The Repairer of Reputations" – the first story in the collection, though probably not the first written – that cements his reputation.

I don't know anything quite like it. Chambers envisions a 1920s utopian New York that includes sanctioned euthanasia. Chambers solidifies its social reality by naming those at the opening ceremonies, quoting from their fatuous speeches, and later offhandedly mentioning lone agonizers dashing into the termination building. This routine-acceptance approach nails his alternate universe in place simply as background for a tale of unfolding mania and madness. It makes the fantasy immediate and palpable. "The Repairer of Reputations" is one of the finest stories in the English language.

The second major group of stories in the collection, each named for a Parisian street, ignores the "Yellow King" theme and concentrates on the Parisian art-student world of the Latin Quarter. Of these, "The Street of the First Shell" is a harrowing war tale – not one wit less so for being set, again, in an alternate universe, this time a Paris under siege from Germans in an unnerving presentiment of World War I. Jack Trent's haphazard stumble into a battle where no one knows the object or even the location brings us closer to war than most of us will ever want to get. The other three tales in this group are love stories that often veer out of control and reach no particular end, but they still scintillate with detail.

Between the two major sections lie "The Prophet's Paradise," a Gertrude Steinish (though pre-Gertrude Stein) bit of cumulative repetition, and "The Demoiselle d'Ys," a displaced-time story with descriptions of a desolate moor that might humble Thomas Hardy. Altogether, The King in Yellow should be required reading for anyone who wants to examine the possibilities of the English language. You can download it as a Gutenberg text.

Another aged science fiction novel, 40 pages of introduction, 29 pages of footnotes, seven of bibliography.

Ignatius Donnelly was a peculiarly American kind of oddball, a late-Victorian political radical rebelling against the technocratic subjugation of the masses while dreaming of a workers' utopia. Or more realistically, dreaming the nightmare in which it could not be realized.

Originally released in 1891, Caesar's Column was republished as part of a Wesleyan series of resurrected SF that included Jules Verne and many others. Donnelly, born in Philadelphia, took himself to the Midwest, joined the farmer-worker political movement, and was elected a state and national representative, as well as the youngest lieutenant governor of Minnesota (sort of a reverse earlier incarnation of "boy wonder" Harold Stassen, who began politically as Minnesota governor and flamed out in Philadelphia as president of the University of Pennsylvania). Donnelly also wrote a "non-fiction" best-seller about Atlantis from which most modern undersea mythology springs. This from the intro by Nicholas Ruddick, which is quite good.

With his political career in sad shape, he wrote Caesar's Column (under a pseudonym), again set in a futuristic New York (1988), where the lower classes have been reduced to chattel. Plot: Gabriel Weltstein arrives from his native Swiss colony in Uganda and writes of his experiences to his brother. Initially overwhelmed by the luxury of the metropolis, he is quickly appalled by the treatment of the underclass, becomes involved with the mysterious Brotherhood of Destruction, rescues his true love from the clutches of Prince Cabano (head of the Oligarchy) and watches the inevitable cataclysmic downfall of civilization.

Is it any good? Hmm, let me temporize: The political pontificating is godawful, a soporific rendering of social theory in long paragraphs. Ignore it and turn the pages. His view of the future is a silly hash, with great airships and trains overhead but everyone on the street riding in horse and carriage. In his descriptions, Donnelly often generalizes when he should be specific and vice versa. Most of his characters have the thickness of a mouse fart.

A basic problem, as in most utopian work, is that the stratified classes become monoliths: The Oligarchs meet and plan universal oppression. The workers march in despairing lockstep. But this just isn't how real human beings behave. No matter how elite, they have personalities. No matter how destitute and hapless, they still jostle and joke.

And yet ... A long aside on his friend Max's rescue of a young stage singer from a life of degradation has a Dickensian solidity, and the final conflagration, when the workers arise in thunderous mass to destroy America and Europe, has spine-chilling moments, especially Max's horrifying revenge on those who imprisoned his father. Donnelly is definitely at his best when he accentuates the negative.

But the most peculiar aspect of Caesar's Column (one not noted in the intro) is that Donnelly, the perennial politician, never mentions government – city, state or national. This must be a conscious omission, but to what point? Maybe Donnelly couldn't handle the complication. Or he had given up on politics altogether.

You can download for free from Gutenberg, without the Ruddick introduction, or in costly paper with the intro.

by Derek Davis