The House of D

As one of his final acts in office, Mayor Jimmy Walker broke ground in 1932 for the New York City House of Detention for Women, built on the site of the old Jefferson Market jail in Greenwich Village and colloquially known as the House of D. According to sociologist Sara Harris’ Hellhole (on John Waters’ list of recommended reading), It was intended as a model of prison reform. Opened in 1934, the twelve-story monolith of brownish brick with art deco flourishes loomed behind the old Jefferson Market courthouse on Sixth Avenue, looking more like a stylish if somewhat cheerless apartment building than a prison. Windows were meshed instead of barred, and the one sign on its exterior merely gave the address, “Number Ten Greenwich Avenue.” There were toilets and hot and cold running water in all four hundred cells, and it was going to focus on rehabilitating its inmates – prostitutes, vagrants, alcoholics and/or drug addicts – rather than merely punishing them. From the start the reality was at variance with the intentions, and the facility quickly became infamous as a combination of Bedlam and Bastille. Within a decade it was chronically overcrowded with a volatile mix of inmates: women who couldn’t make bail awaiting trials that were sometimes months off, women already convicted and serving time, alcoholics and addicts, the mentally ill, violent lesbian tops, street gang girls, hookers and other lifelong multiple offenders, and teenagers spending their first nights behind bars. Tougher, more experienced prisoners brutalized and sexually assaulted the weak and inexperienced. So, of course, did the staff. The halls rang with the howls of inmates suffering the agonies of drug or alcohol withdrawal. There were cockroaches and mice in the cells and worms in the food. Village lesbians called it the Country Club and the Snake Pit. The IWW organizer Elizabeth Gurley Flynn did time in the House of D, as did accused spy Ethel Rosenberg and Warhol shooter Valerie Solanas. In 1957, Dorothy Day, founder of the Catholic Worker movement, spent thirty days there for staying on the street during a civil defense air raid drill. Her ban-the-bomb supporters picketed outside every day from noon to two; the Times called them “possibly the most peaceful pickets in the city.”

Despite its bland exterior, the House of D made its presence very known in the neighborhood through the daily ritual of inmates yelling out the windows or down from the exercise area on the roof to the boyfriends, girlfriends, dealers and pimps perpetually loitering on the Greenwich Avenue sidewalk – a carnivalesque Village tradition for almost forty years. Waters first caught the spectacle in the early 1960s. “It was amazing. No one can ever imagine what that was like. All the hookers would be screaming out the windows, ‘Hey Jimbo!’ And all the pimps would be down on the sidewalk yelling stuff.” Writer and film producer Jeremiah Newton initially encountered it at around the same time. “It was this huge, monolithic building, looking like the building the Morlocks dragged the Time Machine into, and the girls were always yelling down, screaming obscenities and throwing things out the window. It was the biggest building there. I sat on a stoop watching the people walk by. I’d never seen anything quite like it before.” The Village writer Grace Paley lived near the facility in the 1950s and 1960s, and walked her kids past it regularly. She wrote that “we would often have to thread our way through whole families calling up – bellowing, screaming up to the third, seventh, tenth floor, to figures, shadows behind bars and screened windows, How you feeling? Here’s Glena. She got big. Mami mami, you like my dress? We gettin you out baby. New lawyer come by.”

Women arrested at antiwar rallies during the Vietnam era found themselves locked up in the House of D with the hookers, junkies, crazies and butch lesbians. On Saturday, February 20 1965, two eighteen-year-old college students, Lisa Goldrosen of Bard and Andrea Dworkin of Bennington, were arrested during an antiwar protest at the UN and sent to the House of D. There, they later testified, they were brutally mistreated and humiliated by male doctors “examining” them for venereal diseases, and forced constantly to fend off the rough advances of other inmates. They were not allowed to use a telephone until Monday. That March, the New York Post ran an exposé based on their testimony. They didn’t experience anything other women hadn’t for thirty years by then, but in the 1960s those other inmates were overwhelmingly poor black and Hispanic women. Dworkin and Goldrosen were white, middle-class college coeds. As so often happens, that’s what it took to generate public outrage.

When Grace Paley herself was arrested at another war protest some months later, she was detained in the facility. Conditions had slightly improved in light of the outcry the Post had stirred up. Paley had been arrested before at antiwar protests, but it had always resulted in at worst overnight stays. This time a judge threw the book at her and gave her six days. “He thought I was old enough to know better,” she later wrote, “a forty-five year old woman, a mother and teacher. I ought to be too busy to waste time on causes I couldn’t possibly understand.” At least she could look out her cell window and watch her kids walking to school.

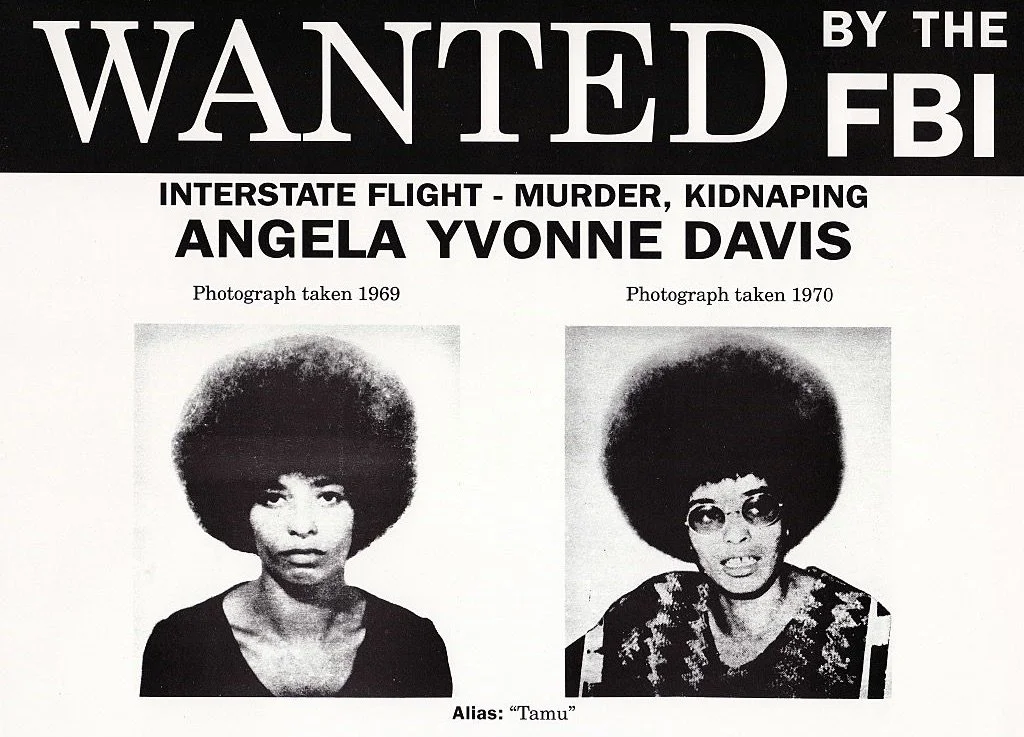

In October 1970, Angela Davis was arrested in the Howard Johnson Motor Lodge at Eighth Avenue and Fifty-First Street and taken to the House of D. It was not her first time in Greenwich Village. She was born in 1944 in Birmingham, Alabama, where her father was a car mechanic and her mother was a teacher and a civil rights activist. They lived in a black neighborhood called Dynamite Hill because the Klan had firebombed so many homes there. With help from the American Friends, she and her mother moved to New York, where her mother studied for her Masters at NYU while Angela attended Elisabeth Irwin High School in the Village. She went on to study philosophy at Brandeis, the Sorbonne, and at the University of California, earning her Ph.D. One of her teachers was Herbert Marcuse. By the late 1960s she was an avowed Communist, a member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and affiliated with the Black Panthers. She lectured in philosophy at UCLA until 1969, when her Communist and radical affiliations got her fired.

In August of 1970 a black teen named Jonathan Jackson took over a Marin County courtroom and demanded the release of his older brother, Panther member George Jackson, from nearby Soledad prison. He took the judge, the district attorney and three jurors hostage. In the attempted getaway, Jackson, the judge and one other person were shot and killed. When police discovered that Davis, who knew George Jackson, was the registered owner of Jonathan’s weapon, she was charged as an accomplice to murder, a capital crime in California. She fled the state, which put her on the FBI’s most wanted list. A beautiful twenty-six-year-old with a huge and magnificent Afro, she became a global pop star of the revolution a la Che Guevara. When the FBI arrested her she’d spent a few days walking openly in Times Square, unrecognized because she’d slicked down the Afro and dressed like an office worker.

Within thirty minutes of her being locked up in the House of D a crowd of protesters began to gather outside the monolith, chanting; prisoners stood in their windows and chanted along, their fists raised. The NYPD sent a Tactical Defense Force unit – riot police – and House of D officials turned off all the lights inside, hoping to quiet things down. Instead, women set small fires in their cells, and demonstrators cheered the flickerings in the windows. They dispersed without major incident. Placed in isolation, Davis went on a ten-day hunger strike. She spent nine weeks in the facility while fighting extradition to California, where, she was quite convinced, she’d be convicted and put to death. In fact she would be acquitted of all charges in a San Francisco courtroom in 1972, after spending eighteen months behind bars.

Davis was the facility’s last celebrity tenant. Through the 1950s and 1960s, Greenwich Village civic and neighborhood groups had constantly called for the facility to be removed to some location more appropriate, which is to say far away from where they lived and walked their children to school. More liberal souls in the neighborhood thought it should stay, fearing that if the women were shifted to some more isolated location they might be all the more easily mistreated. Before he wrote the hit Broadway musicals Hello, Dolly! and La Cage aux Folles, Villager Jerry Herman wrote a satirical revue called Parade, which included a song about the House of D controversy:

Don’t tear down the House of Detention

Keep her and shield her from all who wish her harm

Don’t tear down the House of Detention

Cornerstone of Greenwich Village charm…

So I say fie, fie to the cynic

Know that there’s love in these hallowed walls of brown

There’s love in the laundry, there’s love in the showers,

There’s love in the clinic

'Twas built with love, my lovely house in town

Save the tramp, the pusher and the souse

Would you trade love for an apartment house?

Dworkin and Goldrosen’s testimony before a commission studying conditions at the House of D helped lead to its being shut down in 1971. Inmates were moved to a new facility on Rikers Island. After some debate about possible new uses for the Village monolith, it was simply torn down in 1973. The site is now a small, fenced-in garden. In 1974 Tom Eyen’s spoofy play Women Behind Bars, set in the House of D in the 1950s, premiered. John Waters’ star Divine performed in a later production.

by John Strausbaugh