The Mad Gasser of Mattoon

While it must be admitted that no country on earth can top India when it comes to mass hysteria—I mean, the Indians really, really know how to panic over silly nonsense—the United States comes in a very close second. Despite sneering American press coverage of, say, the Monkey Man hysteria in north central India in the late Nineties, it seems we aren’t nearly so rational and sophisticated a population as we’d like to believe. Whether confined to small rural communities or spread nationwide, delightfully stupid instances of mass hysteria are sprinkled liberally throughout our history. Orson Welles’ 1938 War of the Worlds broadcast was small potatoes compared to some of the seriously dumb crap stalwart Americans have panicked about. From the Winsted Wild Man, to the Great Airship of 1897, to both Red Scares, to the child-raping Satanic cult hysteria of the Eighties, to the post-9/11 fear of, well, pretty much everything, to the Ninja Burglar who terrorized the residents of Staten Island for nearly a decade, Americans are just as primed and ready to start flapping their arms and trampling one another, as Rod Serling pointed out in “The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street” (1960), whenever the lights blink. Today, as fed by media both legitimate and less so, America as a whole seems to be one ugly, sloppy, rolling ball of mass hysterias. We are a gullible, susceptible people.

Although a few sillyassed contemporary revisionists are attempting to rewrite history, claiming the incidents that took place in Mattoon, Illinois in the Fall of 1944 really were the work of a shadowy and diabolical madman, their efforts are about as worthwhile as those of the hundreds of researchers who’ve claimed they’ve discovered the true identity of the (equally fictional) Jack the Ripper. As things stand, The Mad Gasser of Mattoon remains a perfect textbook example of American mass hysteria at its finest.

Mattoon was a small, quiet community in central Illinois, home to a few factories but far from the bustle of Chicago, Springfield or Champagne-Urbana. In 1944 it was even quieter than usual, considering most of the able-bodied men in town had been shipped off to the war.

Although the invasion of Normandy two months earlier seemed to bode well, as with the rest of the country there was still a palpable paranoia in the air that infiltrated most of the women, children and elderly residents who had been left stateside. They worried not only about the young locals in Europe and the South Pacific, but also about what those sinister Germans and Japs might have up their dirty sleeves. And those were only the big things to worry about. There was plenty else, too, all the day-to-day small town fears, especially those harbored by lonely middle-aged women.

On the night of August 31st, Urban Raef and his wife were awakened by a strange smell in their bedroom. The smell sickened both of them. Convinced there was a gas leak, Mrs. Raef attempted to get out of bed to check the stove’s pilot light, but found she couldn’t move her legs.

That same night, a young mother in the same neighborhood woke up when she heard her daughter coughing in another room. As with Mrs. Raef, when she tried to get out of bed to check on the girl, she found her legs seemed to be paralyzed. In both cases the symptoms passed relatively quickly, and the incidents never made it into the papers. Not until later, anyway.

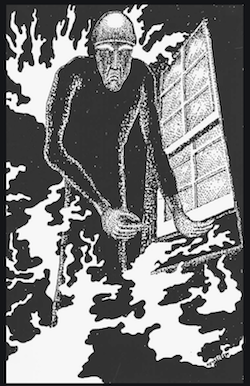

Around 11PM the following night, Bert Kearney, a local cab driver, still had an hour and a half left on his shift. Back home, his wife was awakened by what she described as a sweet odor permeating the room. As the smell grew stronger. Her legs began to feel weak, so she called her sister, who was living with them at the time. When the sister entered the room, she not only smelled the sweet odor, but pointed out it was coming through the open window. As there happened to be a lot of cash in the house that night—stacks of it, in fact, which the sisters had been counting at the kitchen table earlier in the evening—the pair jumped to the conclusion this strange odor must be the work of a prowler who planned to rob them. They called the cops, who could not find any evidence of anything. No odor, no gas, no footprints or fingerprints, no sign of attempted entry. But when Bert returned home after his shift, he claims to have spotted a tall, thin man wearing dark close and a tight cap crouching near the house. Although he gave chase, he soon lost the man in the darkness. The creeping paralysis soon passed, though for the next few days his wife did complain about a burning sensation in her mouth and throat, obvious side effects of the strange gas the tall thin stranger had pumped into the bedroom.

The Kearney’s story made the papers, and that was the end of it. With the details of their harrowing evening now made public, they provided the other residents of Mattoon with the only blueprint they needed.

In the three days following the publication of the Kearney’s story, six other people called the cops to report eerily similar gas attacks with all the same trademarks: a weird smell, partial paralysis of the legs, and a burning sensation in the mouth and throat. One elderly woman claimed the tall, dark-clad Mad Gasser, as he was quickly coming to be known, crawled in through her bedroom window and, um, “attempted to gas her.” A middle aged couple, Carl and Beulah Cordes, returned home on the night of September 5th and discovered a white handkerchief on the back porch. When Beulah picked up the handkerchief and took a big whiff, she said, she began vomiting violently, and from that the pair concluded it must have been left by the Mad Gasser to knock out their dog so he could break into the house. An older woman living with her adult daughter claimed they were in the kitchen when a tall man dressed all in black began rattling the knob of the back door. Finding it locked, he used a syringe to inject the mysterious gas through the keyhole. Both women passed out, waking up several hours later with that telltale burning in their mouth and throats.

Even those who could not claim to be victims of the Mad Gasser themselves spotted him all over Mattoon, sometimes carrying the kind of canister and hose farmers use to spray pesticides. In every instance, the eyewitness descriptions matched perfectly the description Kearney had given the newspapers.

For all their investigating, cops could find no evidence of anything. There was no lasting physical damage to the victims. They could detect no evidence of any strange gas. Although robbery was the presumed motive, no property had been stolen. Even that handkerchief the Cordes’ had found, upon careful analysis, revealed no chemical residue.

The FBI was called in, but likewise found no evidence of anything untoward.

Frustrated by this, as is usually the case, the townsfolk formed roving bands of well-armed angry mobs to patrol the streets at night, determined to capture this Mad Gasser themselves. As official requests that the vigilante groups disband went unheeded, the chief of police was forced to issue a warning begging citizens not to loiter too long on the street for fear they might be mistaken for the Mad Gasser and shot. The town council also issued a plea begging citizens to be real, real careful with those guns.

Roughly two weeks after the Kearney’s story hit the papers, as the number of reported gas attacks in Mattoon approached thirty, the cops stopped caring. Nearly every report could either be explained away quite simply as a reaction to fumes from the local factories, or simply dismissed as false alarms. Considering no evidence was found of anything (save for that evidence created by the supposed victims themselves), this Mad Gasser nonsense was simply a waste of the department’s time, resources, and patience. They had plenty of real local crimes and misdemeanors to deal with as it was.

Not long afterward, and pretty well fed up themselves, town officials came out and told the citizenry to just calm the hell down and stop being stupid. There was no Mad Gasser, and never had been.

After two weeks of public madness and shrill, fear-mongering newspaper headlines, that’s pretty much all it took to bring things to an end. Although it doesn’t seem to work anymore, there was a time, amazingly enough, when all it took was to have someone say, “Oh, just calm the fuck down and go home. You’re all being a bunch of stupid little pansies.”

Seventy-five years after the events in Mattoon, as noted above, a number of revisionists have claimed they’ve identified the mysterious gas that was used, or better still the demented chemist who was behind the attacks, while others note that an eerily similar string of gas attacks took place in Virginia in 1933. It strikes me these people are desperate to sidestep the simple, undeniable reality that people—Americans in particular—are for the most part a stupid, frantic lot eager to not only believe whatever crazy nonsense they’re fed, but run with it as hard as they can.

by Jim Knipfel