The Stoneface Speaks

As the story goes, W. C. Fields once stood up during a screening of a Charlie Chaplin film and angrily announced to the screen and the rest of the audience, “He’s not an actor—he’s a goddamn ballet dancer!”

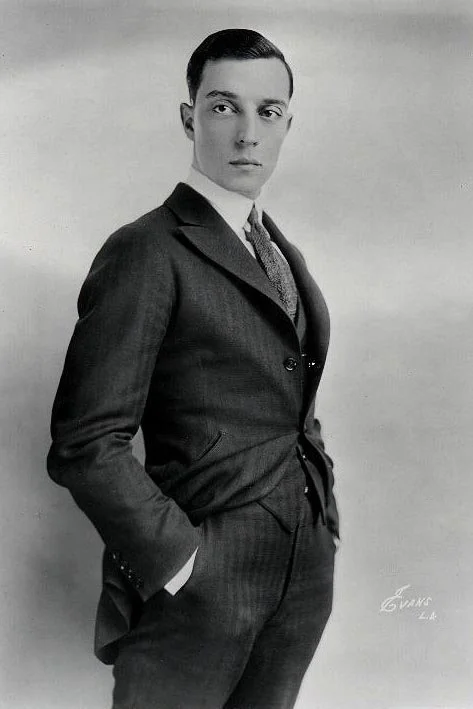

There’s something to that, of course. Through all his antics and pratfalls, Chaplin’s movements were always delicate and graceful. He was always in control, and the well-rehearsed and careful choreography that was behind those pratfalls was right up there on the screen, clear as day. By contrast, the magic of Buster Keaton was that he could take sophisticated stunts that were just as well-rehearsed and carefully choreographed and make them seem clumsy, awkward, and accidental.

And while Chaplin’s characters, though often downtrodden, were still clever enough to use their wits to get out of most any scrape and win the girl in the end, Keaton’s were just, well, hapless. They stumbled out of trouble the same way they stumbled into it—by happenstance and sheer dumb luck. And if he did happen to win the girl in the end it was more likely an accident than the result of any endearing charms he might possess.

As with so many silent stars, the introduction of talkies was a very tumultuous period for Keaton, but not for the usual reasons.

His laconic Kansan twang fit his face and his characters perfectly, with its natural blend of naive, straightforward sincerity and befuddlement. It served the Stoneface well, and added yet another layer to his performances. Or would have, had the studios chosen to capitalize on it.

As the talkie era got underway, Keaton signed a contract with MGM. It kept him working, but in much smaller roles in smaller and weaker films, and without the level of creative control he once enjoyed. A number of personal problems began cropping up as well, and that didn’t help matters.

Then in 1934, he signed with Earl W. Hammond’s Educational Pictures. It seems an odd and unlikely move at first, an iconic comic actor of Keaton’s stature leaving MGM for an industrial house, until you learn that Educational’s real bread and butter at the time was their comic short subjects. The move also once again gave Keaton the creative control he’d been missing, and allowed him to return to the smaller, tighter format where he’d started, and take it in some new directions.

Over the next three years, mostly working with director Charles Lamont (the prolific filmmaker best known for his Abbot & Costello films from a decade later), Keaton would slam out sixteen two-reelers, one after another. While his trademark form of hapless slapstick remained front and center, the addition of sound gave him a new toy. Along with the expected crashis and smashing glass, Keaton also began to play around with the musical and comic potential of natural sounds.

The first half of 1935’s One-Run Elmer, for instance—in which Keaton runs a dilapidated gas station in the middle of nowhere—is played in near silence, save for the squeak of a rocking chair, a cowbell, some dropped change, and the clinking of a gas pump. Somehow, though, through a combination of timing and gesture, he’s able to turn it all into a brilliant and hilarious (if discordant) symphony. In the years that followed, it’s a routine that would be adapted by everyone from Ernie Kovacs to Ennio Morricone.

Then there’s Elmer. With the exception of two of the sixteen films (1934’s The Gold Ghost and 1935’s Palooka from Paducah), Keaton’s on-screen persona throughout the series was Elmer, the wide-eyed, naive, always helpful, always hopeful, and perhaps too-polite Midwestern lad with a bad habit of innocently fumbling his way into trouble and falling in love with every pretty girl he sees. Elmer actually first appeared in 1932’s The Passionate Plumber, but in these shorts Keaton had the space and the freedom to develop him more fully.

Here once again sound becomes an invaluable addition. Not only is Keaton’s voice perfect for the character, but he also reveals himself to have perfect, low-key verbal timing.

In 1935’s Hayseed Romance, he arrives at a farmhouse in answer to a newspaper ad. The large and severe woman who runs the farm tells him, “I’d offer you something to eat, but we’ve already had dinner.”

“Oh.”

“But you can wash most of the dishes if you like.”

He waits just the briefest of beats before saying, “Thanks!”

It’s a quick exchange that could easily slip past some viewers and certainly wouldn’t translate well as an intertitle, and the Elmer shorts are full of subtle bits like that. Quiet, off the cuff remarks that likely never would have cut it in the silents. (When Elmer stops at a drive-in restaurant wearing a boy scout uniform, a waitress asks him in passing, “So what are you, a big game hunter or just giving your knees an airing?”)

Oh, the mayhem and misadventures and hijinx are there as well in spades—he had a knack for cramming an awful lot of material into a very small space—and as time went on he ratcheted up both the verbal and physical humor a few notches. While maintaining a solid base of the comedy that made him a legend of the silent era, he used sound in new ways to push it in some very interesting directions. It was the last great period of his career, and you have to wonder where he might have gone with it had he been able to continue. Sadly, the films he made for Educational were lost and all but forgotten until 2010, when Kino released their Lost Keaton set, which collected together all sixteen educational shorts. So the films have been saved for us, but it does little to help Keaton. After the Elmer films came a long and slow slide into the bottle and smaller roles and cameos, mostly for people who wanted him to just do sad pratfalls and keep his damn mouth shut.

by Jim Knipfel