Las Momias de Guanajuato

Gazing at the faces of Guanajuato's famous mummies can make you wonder what kind of expression you'll wear when you face death. Will you be as indignant as this woman, her spectacles smashed crooked, her dark hair a stormy swirl on top of her head, gaping her mouth wide in a silent shout of outrage? Or feebly defiant like this other woman, naked except for a bracelet, who sticks her withered tongue out? Will you lower your face in humble resignation, like this man draped in the dusty rags of what must have been his finest suit? Or fake nonchalance, like this Churchillian burgher, bald and still looking portly even though he's a husk, who seems about to give a speech to dead Rotarians?

Mae Clarke: An Honest Woman

There is a certain look of wary, contained bitterness that you see on women’s faces in movies from the early thirties. Their eyes become veiled; the women seem to retreat inside themselves defensively, tasting memories of hurt and humiliation, of men who made them feel dirty and how they had to keep on smiling and flirting so they could pay the rent on their drab hall rooms and buy their automat coffee. It’s the look of the chorus girl who has learned to protect herself by shutting down the gates, even while wiggling in her scanties. Barbara Stanwyck carried it throughout her long career, like an eternally livid scar; “bubbly” Joan Blondell wore it quietly; and in Waterloo Bridge (1931) it’s branded on the face of Stanwyck’s one-time roommate, Mae Clarke.

Waterloo Bridge opens with a shorthand summation of a chorus girl’s life. It’s the all-hands-on-deck finale of a fluffy musical revue on the last night of its run. The camera pans past the interchangeable faces of the chorines in their platinum wigs and sparkly tricorn hats, and comes to rest on Mae Clarke, as Myra Deauville. She throws up her arms and gives an open-mouthed laugh, then lapses into exhausted boredom, then switches on the faux exuberance again, then yawns. Throughout the film she keeps doing this: putting on her game “Hello, big boy” act and then flinging it aside with furious disgust. Director James Whale doesn’t bother with transitions, but conveys the whiplashing ups and downs of his heroine’s life through blunt cuts. We see her backstage in her bra, receiving a white fox stole from an admirer; in the next scene, out of work for two years, she’s wearing the stole low around her décolletage, standing outside the theater with a fellow hooker looking for pickups. (The setting is World War I, but when Myra says hopefully, “I’ll get a job soon,” 1931 audiences must have foreseen the worst.)

Spotting a prospective john, the friend primps and smiles flirtatiously, while Myra turns on him with a defiant yet seductive scowl; a sullen, defensive stance that she assumes throughout the film. She suffers from incurable decency, which becomes a scalding torment when she meets an innocent young doughboy who has no idea that she’s a prostitute. She brings Roy (Kent Douglass) to her flat, intending to pluck him for the back rent she needs to satisfy her sour-faced landlady. But it’s too easy: when the sweet, boyish soldier pleads with her to accept the money, she abruptly drops the good-natured frankness she’s been charming him with and turns hard and caustic, hating him because she hates herself for tricking him. She’s so stung with hurt pride that she has to lash out and hurt someone else. Preparing to go out on the streets after sending him away, she stares at her hard face in the mirror, dabbing make-up on the rigid mask that barely conceals the tired, angry sadness beneath.

Waterloo Bridge is the only film that reveals the breadth of Mae Clarke’s talent. In other movies she played nice, open-faced girls or mean, petulant golddiggers. As Myra she is a kaleidoscope of confused emotions. Her best scene comes when Roy tells her he loves her: she turns away, hunched as though against a cold rain, her eyes narrow and tense. This is the final insult from life: for her dream guy to come along too late, when she feels unworthy of him. Leaving, he kisses her hand, and reacting to this tribute she passes through exaltation, anxiety, and rage—growling as she forces herself to cast it aside. She’s too honest to grab the expedient of letting a man make “an honest woman” out of her. But we know she loves him, because in the next scene she’s trying to knit him a pair of socks, sitting at the breakfast table with her hair piled on her head, a cigarette planted in her mouth, mangling the stitches.

The worst is yet to come: well-meaning oblivious Roy tricks her into visiting his posh family in the country. They’re kind and welcoming in that self-satisfied upper-class way bound to cause excruciating discomfort in someone like Myra. Roy’s mother (Enid Bennett) is polite, complacent and deadly. Watching her sweetly confide to Myra that she doesn’t want her son to marry a chorus girl, but that she knows she has nothing to fear from such a “fine” person, is almost unbearably painful. Reduced to abject guilt, Myra confesses her true profession and pitifully sobs, “I just wantcha to know, I could’ve married him…”

The House of D

As one of his final acts in office, Mayor Jimmy Walker broke ground in 1932 for the New York City House of Detention for Women, built on the site of the old Jefferson Market jail in Greenwich Village and colloquially known as the House of D. According to sociologist Sara Harris’ Hellhole (on John Waters’ list of recommended reading), It was intended as a model of prison reform. Opened in 1934, the twelve-story monolith of brownish brick with art deco flourishes loomed behind the old Jefferson Market courthouse on Sixth Avenue, looking more like a stylish if somewhat cheerless apartment building than a prison. Windows were meshed instead of barred, and the one sign on its exterior merely gave the address, “Number Ten Greenwich Avenue.” There were toilets and hot and cold running water in all four hundred cells, and it was going to focus on rehabilitating its inmates – prostitutes, vagrants, alcoholics and/or drug addicts – rather than merely punishing them. From the start the reality was at variance with the intentions, and the facility quickly became infamous as a combination of Bedlam and Bastille. Within a decade it was chronically overcrowded with a volatile mix of inmates: women who couldn’t make bail awaiting trials that were sometimes months off, women already convicted and serving time, alcoholics and addicts, the mentally ill, violent lesbian tops, street gang girls, hookers and other lifelong multiple offenders, and teenagers spending their first nights behind bars. Tougher, more experienced prisoners brutalized and sexually assaulted the weak and inexperienced. So, of course, did the staff. The halls rang with the howls of inmates suffering the agonies of drug or alcohol withdrawal. There were cockroaches and mice in the cells and worms in the food. Village lesbians called it the Country Club and the Snake Pit. The IWW organizer Elizabeth Gurley Flynn did time in the House of D, as did accused spy Ethel Rosenberg and Warhol shooter Valerie Solanas. In 1957, Dorothy Day, founder of the Catholic Worker movement, spent thirty days there for staying on the street during a civil defense air raid drill. Her ban-the-bomb supporters picketed outside every day from noon to two; the Times called them “possibly the most peaceful pickets in the city.”

Great Zilches of History

Film is light. There are times, though, when that light may take on a Stygian cast, burning with a flamme noire severity, a weird and otherworldly keenness. Or it may burn lurid and loud — especially if it’s a very old film, acting like a séance that summons the unruly dead. The darkness in cinema best typified by that form we call film noir is in its essence an extension of the peculiarly American darkness of Edgar Allan Poe.

Amigo Gigolo: Gilbert Roland

In 1905, in Ciudad Juáraz, Chihuahua, Mexico, a bullfighter and his wife gave birth to a son, Luis Antonio Dámaso de Alonso. Young Luis intended to become a bullfighter just like his father, but when the family moved to California, he fell into acting after being cast as an extra in the Lon Chaney version of The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923). Two years later, Ben Schulberg at Paramount studios cast the 20-year old Luis opposite Clara Bow in a college comedy, The Plastic Age, where he was first billed as Gilbert Roland. He had the sort of looks that seemed different from different angles: romantic in profile, but somewhat shifty when he was seen full face with his eyes narrowed. When he opened his eyes wide, however, their greenness had a heart-stopping effect, even in black and white films. Many of his leading ladies took notice.

The Invisible Border: “The Man Between”

“Wickedness,” Oscar Wilde wrote, “Is a myth invented by good people to account for the curious attractiveness of others.” Both The Third Man (1949) and The Man Between (1953), a film that suffers from perennial unfavorable comparison to Carol Reed’s earlier masterpiece, revolve around men whose attractiveness is inseparable from their amorality. But while Grahame Greene’s script for The Third Man ultimately strips away Harry Lime’s glamour, reducing him to a scurrying sewer-rat and a suicidal nihilist, The Man Between embraces the tragic romanticism of its more ambiguous anti-hero.

Gore Vidal of the 1940s

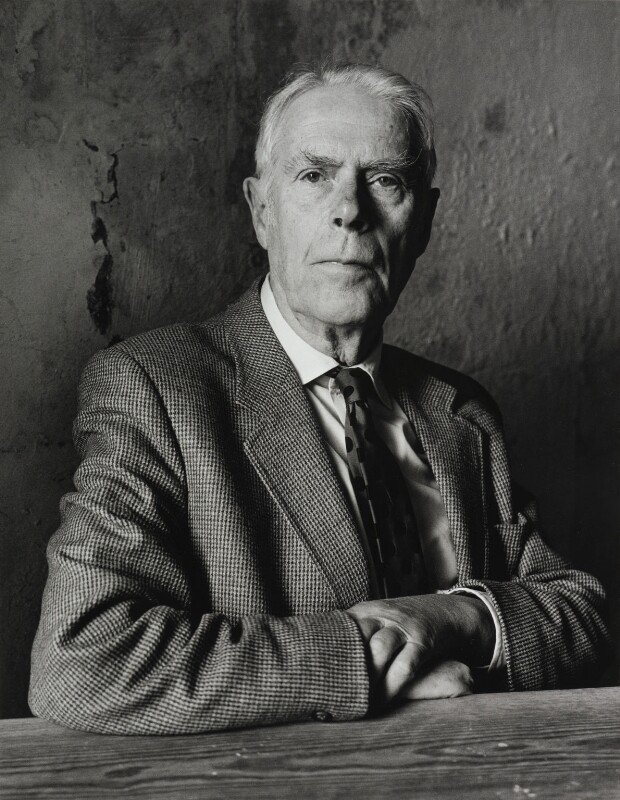

You don’t often hear people referencing Philip Wylie these days, but from the late Twenties through the late Sixties, he was one of the most popular, prolific, influential and at times controversial writers in America. Wylie not only wrote novels, short stories, and articles for everything from the Saturday Evening Post and Popular Mechanics to Harper’s and academic journals, but newspaper columns and screenplays as well. Part of the problem, why he’s so thoroughly forgotten today, may be that even in his lifetime, as ubiquitous as he was, he was almost impossible to pin down. In many ways, he was reminiscent of Gore Vidal, and it’s entirely likely, and for the same reasons, Gore Vidal will be just as sadly forgotten forty years from now.

The son of a Presbyterian minister, Wylie grew up in Montclair, New Jersey and graduated from Princeton in 1923. He began writing science fiction and mystery stories for the pulps, and his 1930 novel Gladiator has long been rumored to have been the central influence on the creation of Superman. Other stories and novels were said to have inspired Flash Gordon and Doc Savage. In the early Thirties he also began writing screenplays, working on both Island of Lost Souls and James Whale’s The Invisible Man. But Wylie was a polymath with a solid working knowledge of psychology, biology, physics, anthropology, sociology and engineering, elements of which would work their way into not only his science fiction, but his social criticism, his writings on policy issues, even articles about deep sea fishing and gardening. A 1952 article on growing orchids led to a nationwide gardening fad. He wrote cleverly and thoughtfully about gender issues, and though grossly misinterpreted at the time as a misogynist, Wylie, as a male writer, was actually decades ahead of his time. He wrote about UFOs and education. He railed against censorship of any kind. He touted the importance of civil defense preparedness years before backyard fallout shelters or duck and cover drills came into vogue. His incredibly popular “Crunch & Des” stories, about the adventures of a charter fishing boat captain in the Gulf of Mexico, resulted in a short-lived 1955 television series starring Forrest Tucker, and his 1933 novel When Worlds Collide was adapted into George Pal’s 1951 apocalyptic sci-fi epic.

His 1945 speculative short story “The Paradise Crater” envisioned the Nazis using Uranium 237 to develop an atomic bomb. Problem was, the Manhattan Project was still underway, the first atomic test was still a few months down the pike, and no one was supposed to know anything about Uranium isotopes, let alone their role in the development of nuclear weapons. As a result, Wylie found himself placed under house arrest until it could be determined he wasn’t a spy. Ironically, his continued interest in the science and sociology of nuclear war (it would be at the heart of several novels and countless non-fiction essays) earned him a job as an advisor to the precursor of the Atomic Energy Commission.

He was also a book editor and the one-time director of the Lerner Marine Laboratory in Florida. Oh, he did every damn thing, but what he did best of all, it seems, was piss people off.

As a sharp-eyed satirist, iconoclast, and social critic, Wylie (to quote Mike Wallace from a 1957 television interview) “ violated taboos by attacking American moral values, Christianity, Doctors, Teachers, and Statesmen, to name just a few.” A number of those attacks can be found among the far-reaching essays collected in his 1942 anthology Generation of Vipers. Apart from When Worlds Collide and its sequel, After Worlds Collide, Generation of Vipers was among the first of Wylie’s books I encountered randomly. I saw a first edition selling for cheap at Gotham Book Mart and dug the title, so picked it up. It was astonishing, not only for the savagery of the prose—which foreshadowed Hunter Thompson—but also his range of targets. How he could publish wicked attacks on American morality, religion, and politics in those early gung-ho years of WWII without being charged with treason is nothing short of amazing. More amazing still, he was skewering the myth of Eisenhower’s America a decade before Eisenhower’s America existed.

Of all the attacks aimed at a fistful of sacred cows, none was more inflammatory, none raised more of a shrill public shitstorm than is attack on what he called “Momism.” To quote just a brief passage:

“"Men live for her, and die for her, dote upon her, and whisper her name as they pass away. In a thousand of her, there is not enough sex appeal to budge a hermit ten paces off a rock ledge. She plays bridge with the stupid veracity of a hammerhead shark. She couldn’t pass the final examinations of a fifth grader.”

Okay, you can attack the government, attack the Catholic Church, attack the schools and the stupidity of the masses all you want and few will raise an eyebrow, but for godsakes the one thing you can’t attack is mom. Fifteen years after its original publication, Wylie was still getting death threats for that essay, and fifteen years later he was still attacking Eisenhower’s America, by name this time, writing “we have gradually become a nation of exalted ignoramuses.” That same year, 1957, he had also just published a screed against organized religion as a whole and Christianity specifically, The Innocent Ambassadors, which was something else you might not want to be doing in 1957. Worse still, he publicly advocated stoning Liberace to death with marshmallows.

Stormy Weather Underground

West Eleventh Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues is one of the “nicest” blocks in Greenwich Village, a leafy street lined with handsome Greek Revival townhouses and stately apartment buildings. One house stands out, literally: 18 West Eleventh, which became an unlikely nexus of privileged status and radical politics during the Vietnam War era.

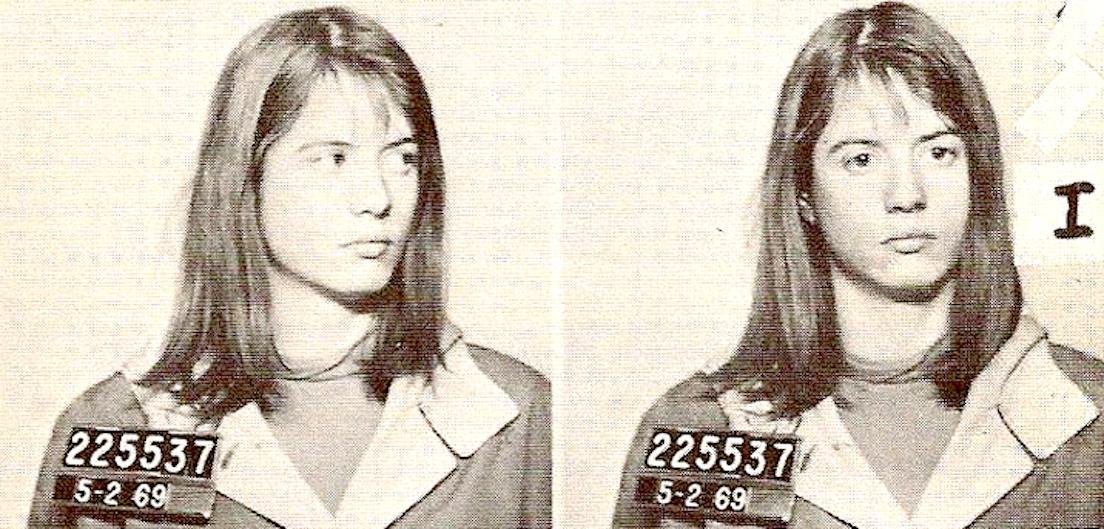

Born in 1945, Cathy Wilkerson grew up in haute bourgeois comfort in Connecticut. When her parents divorced she stayed with her mother; her father, an executive at the ad agency Young & Rubicam, remarried and in 1963 bought 18 West Eleventh. That year Cathy, a sophomore at Swarthmore, was arrested while picketing outside a dangerously decrepit and overcrowded black school in Chester, Connecticut. A few years later she was at SDS headquarters in Chicago editing New Left Notes, SDS’s newsletter. When the Students for a Democratic Society began in 1962 it was mainly involved in civil rights issues, but from the mid-1960s on it grew increasingly active in the antiwar movement. In 1969, SDS claimed a hundred thousand members on college campuses nationwide. Wilkerson attended the national convention in Chicago that June, when SDS burst apart at the seams. Fed up with the organization’s policy of nonviolent protest, which seemed to be having little effect, a faction calling themselves Weatherman from the line in Dylan’s “Subterranean Homesick Blues” essentially hijacked and later dismantled SDS. Among its leaders were Mark Rudd, who as chairman of the SDS chapter at Columbia had led a 1968 student uprising there, and Bernadine Dohrn. Wilkerson went along with them. Weatherman styled themselves as a cadre of the world armed revolt against U.S. imperialism and as a corollary to the Black Panther Party. They adopted Fred Hampton and Mark Clark, two Panthers killed in a police raid, as role models and patron saints. Never more than a thousand committed members nationwide, Weatherman set themselves the goals of radicalizing the nation’s working class, disrupting government and corporate operations, and bringing about the revolution in America by any means necessary. Attempts to organize the working class and to align with the Panthers would fail miserably: Workers beat them up and the Panthers rejected them as “scatterbrains.” Meanwhile their violence alienated the rest of the antiwar movement.

Weatherman’s first public action was a demonstration in Chicago that fall that came to be known as Days of Rage. They’d expected tens of thousands of protesters, but only a few hundred showed up. From its starting point in a park the march flowed out into the streets and soon got out of hand, with protesters breaking car and shop windows. Cops chased them through the streets, shooting a few, bludgeoning and arresting others, including Wilkerson. She was out on bail two weeks later. Having proven to themselves the futility of public demonstrations, Weatherman now turned to direct action. “We will loot and burn and destroy. We are the incubation of your mother’s nightmare,” one of them orated. Looking back on this moment forty years later in her memoir Flying Close to the Sun, Wilkerson writes, “Now it seems fantastic that I responded to the clear signs of political idiocy” by going along. Breaking up into small cells in secret locations around the country, they went into an intense period of self-indoctrination, hoping to transform themselves from middle-class college kids into “more effective tools for humanity’s benefit,” Wilkerson writes. Through grueling, humiliating group interrogations they attempted to purge themselves of personality and individualism to create a faultlessly doctrinaire and obedient collective that was as much cult as Communist, the Borg of the revolution. Because traditional relationships might weaken members’ bonds with the collective, they were supposed to have sex only with randomly assigned partners or in cheerless-sounding group orgies.

They’re Watching You

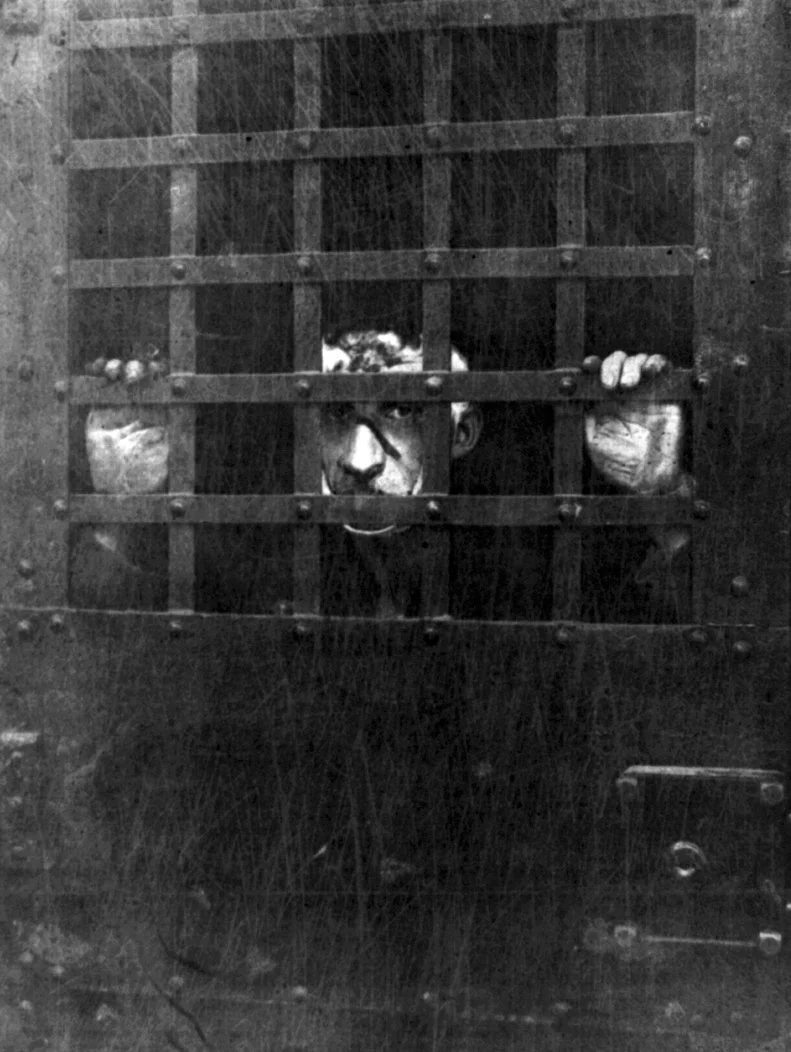

In early cinema, actors kept a wary eye on the camera. Georges Melies performs magic tricks for us, bowing courteously. From his first appearance in tramp drag, Chaplin flirted with or scowled at the lens, reaching through it to seduce his worshippers out there in the dark.

May I Cut In Here?

A Dance to the Music of Time is one of the monuments of 20th-century British literature.

As a monument, it is immediate, cleanly chiseled, foursquare and, despite occasional intricate carvings of angels, stark. As a monument, it does not clearly disclose its sculptor – whether, in this case, it be the author, Anthony Powell, or its universal narrator, Nick Jenkins. And as a monument, at least for me, it is also less “to read” than “to have read.”

Black on Black — The Three Lives of Ulderico Sciarretta

1.

There are many different shades of black. One is particularly hateful to Italian people and will never fade in the collective memory. During the Fascist regime, black was the color worn by the Italian Fascist militia, the “blackshirts”: a tint evoking violence, repression and abuse, a vision soliciting fear, but also a badge which granted power and rewards for those wearing or supporting it, either by belief or personal advantage. Born on August 26, 1906, Ulderico Sciarretta enlisted in the Fascist party at 16, in 1922, soon after the March on Rome. One might say he was quick in catching the spirit of the time. Then, as he later claimed, he had a “vocational crisis”[1] and enrolled in the navy; he did not make much of a career, though: on the contrary, he ended up on trial for violence and outrage.

In 1937 Sciarretta moved to Turin, posing as an accountant, a professional title the police advised him not to use. He set up a tax advice office which in fact was a front for other types of business, not exactly legal. Then came the September 1943 armistice: following the birth of Mussolini’s short-lived Republic of Salò in Northern Italy, Sciarretta acted as a double agent and took part in Fascist raids against the partisans, as a spy of the infamous Fascist brigade “Ather Cappelli” (one of the members was Mario Volonté, Gian Maria’s father). After the end of the war, he was arrested and taken before the Court of Assizes in Turin, together with other war criminals: he was accused of taking part in the murder of the 25-year-old Agostino Priuli, killed in December 1944 during a raid in a workshop where arms for the partisans were assembled and repaired with the steel provided clandestinely by the Lancia car plant. The newspaper La Nuova Stampa described Sciarretta as follows: “Pale, puny, skinny, he even looks sinister.”[2] A woman testified having seen him railing against dead partisans’ bodies, shouting: “Come, mothers, come and see your bandits!” During the trial, the crowd⎯largely composed of relatives of people arrested, deported, tortured or killed by the defendants⎯yelled out loud, “Give them to us!”

Glad Rags: Fashion and the Great Depression

Some years ago, in a breathtaking lapse of taste, The New Yorker published a fashion spread that aped iconic photographs of Dust Bowl migrants. I was as appalled as the next right-thinking person by the pouting models in $400 distressed cardigans pretending to thumb rides along desert highways. But if the charge is infatuation with the aesthetics of the Great Depression, I am guilty, guilty, guilty. Throw me in the clink—just so long as it resembles the hoosegow that Barbara Stanwyck saunters around in Ladies They Talk About (1932).

Why was everything, from automats to automobiles, from nightclubs to radios, from skyscrapers to bus stations, from cocktail shakers to the battered hats on homeless men, so elegant in the thirties? Why did bums back then look better than bankers today? Why are the movies and music, the clothes and every aspect of design from typefaces to elevator panels, so intoxicatingly stylish?