A public boast and a sobering message

1.

My father has Covid.

A friend of mine dated Gaddafi.

I used to be Barbara Steele’s agent.

My dead friend Barbara

—a different one—

appeared to a mutual friend

in a dream. Twice.

Each time, she said,

“I know I’m dead. It’s ok.”

Very deadpan. Just like her.

The Bindlestiff Interviews Noam Chomsky

Meet The Bindlestiff, a reporter wandering our planet in search of humanism, solidarity and esprit de corps — a roving archivist of ideals that, once upon a time, inspired millions. He interviewed Noam Chomsky a year ago when Israel was bombing Gaza heavily. And yesterday (March 23, 2022) The Bindlestiff returned to the Professor with a follow-up question. We present this first dispatch in what The Chiseler sincerely hopes will become a tradition that abides.

The Bindlestiff: This latest assault against Gaza seems contradictory: both part and parcel of Israel’s enduring agenda and more obviously cynical, bearing no relationship to the usual talking points about national defense, etc. Is it wrong to overestimate public opinion as surprisingly informed, seeing through Israel’s state propaganda more swiftly this time around?

Noam Chomsky: Each time Israel launches some barbaric act of terror, its sophisticated Hasbara system faces a more difficult task of justification, and its grip on popular opinion weakens. The horrors of Israel’s latest war against the civilian society in its Gaza prison are impossible to suppress, so propaganda seeks to restrict attention solely to Hamas rockets attacking innocent Israel in an act of unprovoked aggression: every country has a right to defend itself, and in self-defense Israel has been remarkably restrained considering the nature of the Hamas attack.

That still works in some circles, but fewer than before. Though the media do not convey anything like the hideous reality of Israel’s murderous strangulation of Gaza or the regular brutality of the Israeli occupation in the West Bank, nevertheless a fair amount is seeping through, a good deal more than before, enough for many to dismantle the propaganda line.

Self-Indexing and Shifting Spectators in Varda’s Vagabond

Adapted from a lecture given at the Filmmuseum Pottsdam, July 6, 2016.

It’s unfortunate that Agnès Varda only began to assume the status of a major filmmaker after her husband died and she became known as the custodian of Jacques Demy’s precious legacy. Prior to that, she was mainly known, affectionately but somewhat condescendingly, as a sort of mascot of the French New Wave whose public profile remained almost as superficial as that of her eponymous heroine in Cleo from 5 to 7 (1962). And the troubling, ironic sting at the end of La Bonheur (1965) tended to be either misunderstood or ignored. Thanks to the diversity of her films, stylistic and otherwise, she was easy to overlook due to her reluctance to brand herself, unlike her male colleagues.

A Few Queries for Monte Hellman

The cult director of Two-Lane Blacktop talks film theory, painting, politics, and, last but not least, actor Warren Oates.

Despite transparent light and searing heat, all seems frozen. Something clings to the landscape. Amidst Joshua trees and sagebrush, an ineffable presence surrounding even the stinkbugs.This is where George Stevens—who once said that Utah’s western desert ranges “look more like the Holy Land than the Holy Land”—filmed The Greatest Story Ever Told. Soon thereafter, a younger man breathing that same numinous air made a very different kind of movie. In fact, Monte Hellman made two: The Shooting and Ride in the Whirlwind, displaced and gritty, eternally unblessed, a diptych belonging to the Western, yet standing at a slight angle to it in the same breath.

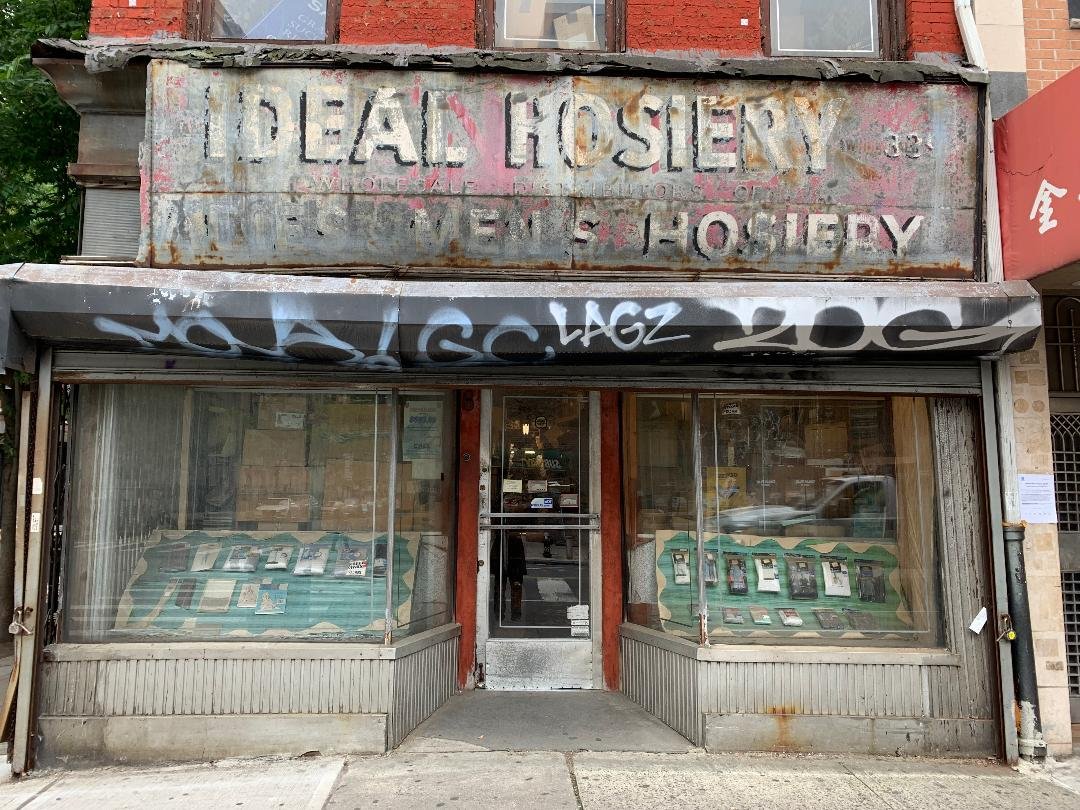

Butter Knife Slide

In the early ’90s, I was the Editor-at-Large at The Welcomat, a Philadelphia-based alternative weekly. I was living in Brooklyn at the time, but every Thursday I would hop on a NJ Transit commuter train for the three and a half hour trip to Philly. After arriving at 30th Street station, I’d walk across the river into Center City to the paper’s offices, which were housed in a building on the corner of 17th and Sansom. I’d make a right in the building’s small lobby, take the elevator to the Third floor, and walk to the back, where the editorial department was located. Even before saying hi to the other editors, I’d drop my bag on my desk, step over to the office boombox, sort through the small batch of cassettes stacked next to it, throw in Delta bluesman Cedell Davis’ debut album, Feel Like Doin’ Something Wrong, and punch the play button. Without fail, once those first notes hit the air, an audible and pained collective groan arose from every throat in the room.

While my own aesthetic sensibilities were just as offended as my co-workers’, over time I came to have a real and solid affection for Davis, the same way you come to cherish a middle child with a droopy eye or a pet rabbit with the mange.

To the uninitiated, the first moments of the opening track on Davis’ album, “I Don’t Know Why,” might have been produced when a large bull walrus with a head cold and an untuned autoharp were tossed into an enormous blender together. Those same listeners might even cynically conclude the album’s title was a direct reference to the last thing Davis muttered before stepping into the recording studio. At the very least, Davis’ caterwauling guitar and his own strangled yelping vocals might be seen as proof positive there really is such a thing as an authentic Delta Blues singer who is absolutely godawful. As one friend put it, “If you’re bad enough, you get to be ‘authentic’.’”

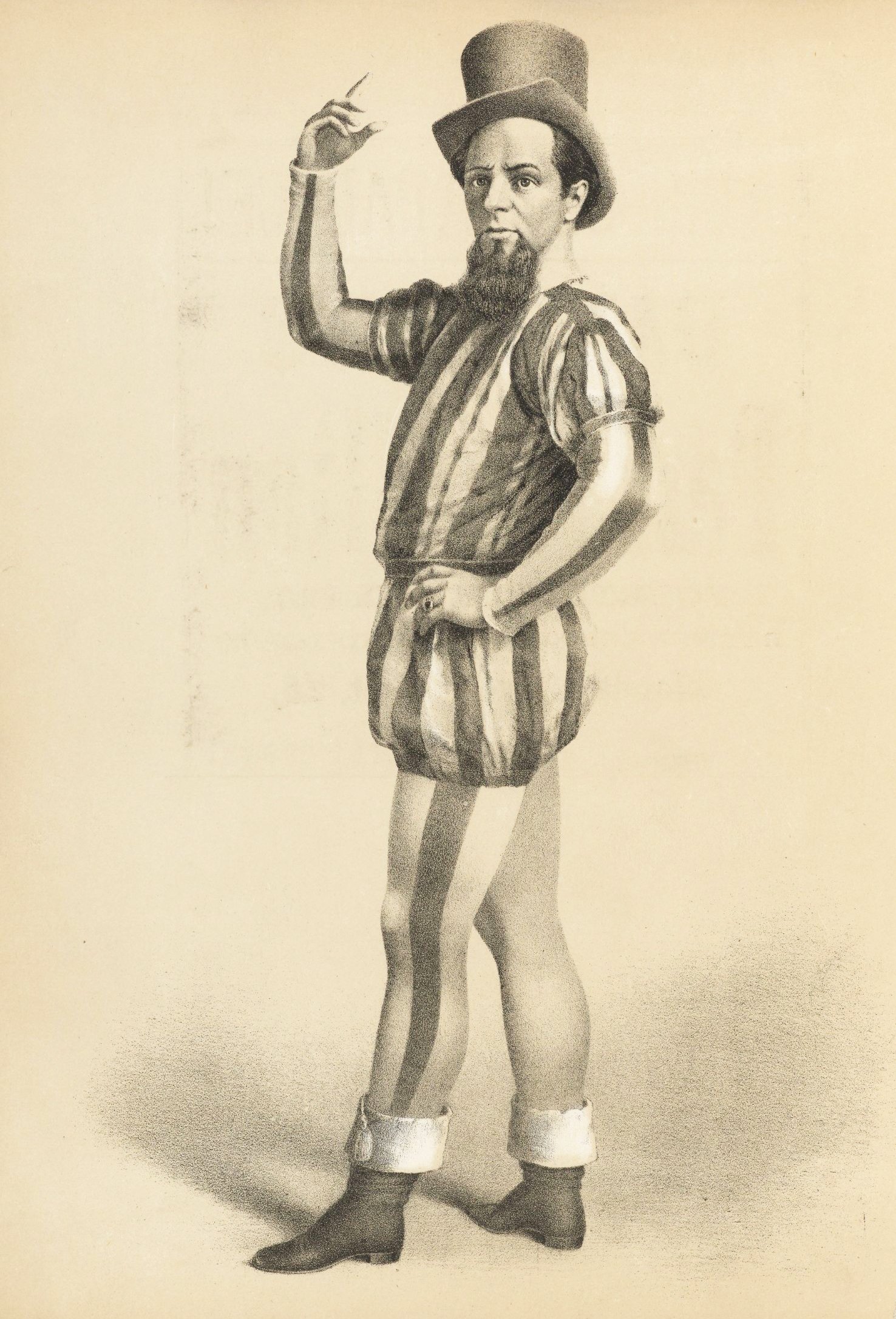

Dan Rice

In the mid-1800s Dan Rice was as celebrated a showman as Barnum, to whom he was often compared. Across a long career he was a clown, a blackface minstrel, a circus impresario of great note, a political orator and a presidential candidate. All sorts of legends and myths grew up around him, many of which Dan, like Barnum, propagated himself. That he invented pink lemonade and the peanut gallery, that he coined the term “on the bandwagon,” that he played cards with Louis Napoleon and was Abe Lincoln’s “court jester,” and many others. One story is still retailed today: that Dan Rice, with his sharp features, signature goatee, top hat and striped outfits, was the model for Thomas Nast’s depictions of Uncle Sam. And something that might sound like legend is actually true: that Dan Rice was a key influence on both Stephen Foster and the Ringling brothers.

Yet where Barnum’s name lived on – if only, in many cases, to be unfairly maligned – Rice’s was already fading when Maria Ward Brown self-published The Life of Dan Rice in 1901, a year after his death. Brown was a relative, to whom Rice had dictated the mostly fanciful stories in the book. Circus history buffs unquestioningly repeated the tall tales in Brown’s book through the twentieth century. Then in 2001 David Carlyon, a former Ringling clown with a Ph.D. in theater history, published his Dan Rice: The Most Famous Man You Never Heard Of, trying to set the record as straight as a pile of myths and legends can be.

In his self-promotions Rice cast himself as a classic Horatio Alger hero who rose up against adversity to great success, and that part at least comes close to the truth. His mother, Elizabeth Crum, was a girl from the straitlaced Methodist camp on the Jersey shore later known as Ocean Grove. In 1821 she met Daniel McLaren at a dance in nearby Long Branch. She ran away with him to Manhattan, stopping for a quick wedding performed by a justice of the peace on the way. Though hasty, it was not a bad union for the girl. McLaren was studying law under Aaron Burr while helping his father run his upscale grocery near City Hall, where Burr and other of the city’s finer types shopped for quality wines and teas. Young Dan was born in the McLaren’s Mulberry Street home in January 1823, and might have gone on to a life of some privilege and comfort had not Elizabeth’s outraged father managed to find her after a long search. He dragged her and the child back to Jersey and had the marriage annulled. According to Brown, he also changed the boy’s surname to Rice, a Crum family name, to signify a total estrangement from the dastardly McLaren. Carlyon doubts it.

The Cinema of Seeing

It is said that stars do not need scripts or mere stories to thoroughly inhabit a motion picture. Histories without language, or even thought, quiver behind their eyes. Their presence—ineffable, diaphanous, seductive—provides the audience a beacon to follow a prefabricated narrative to its only meaningful conclusion. Outside the realm of this splendid cosmology, movies that rely on actors and 'acting,' the common tools of theater, tend to miss the mark when these metaphysics come into play.

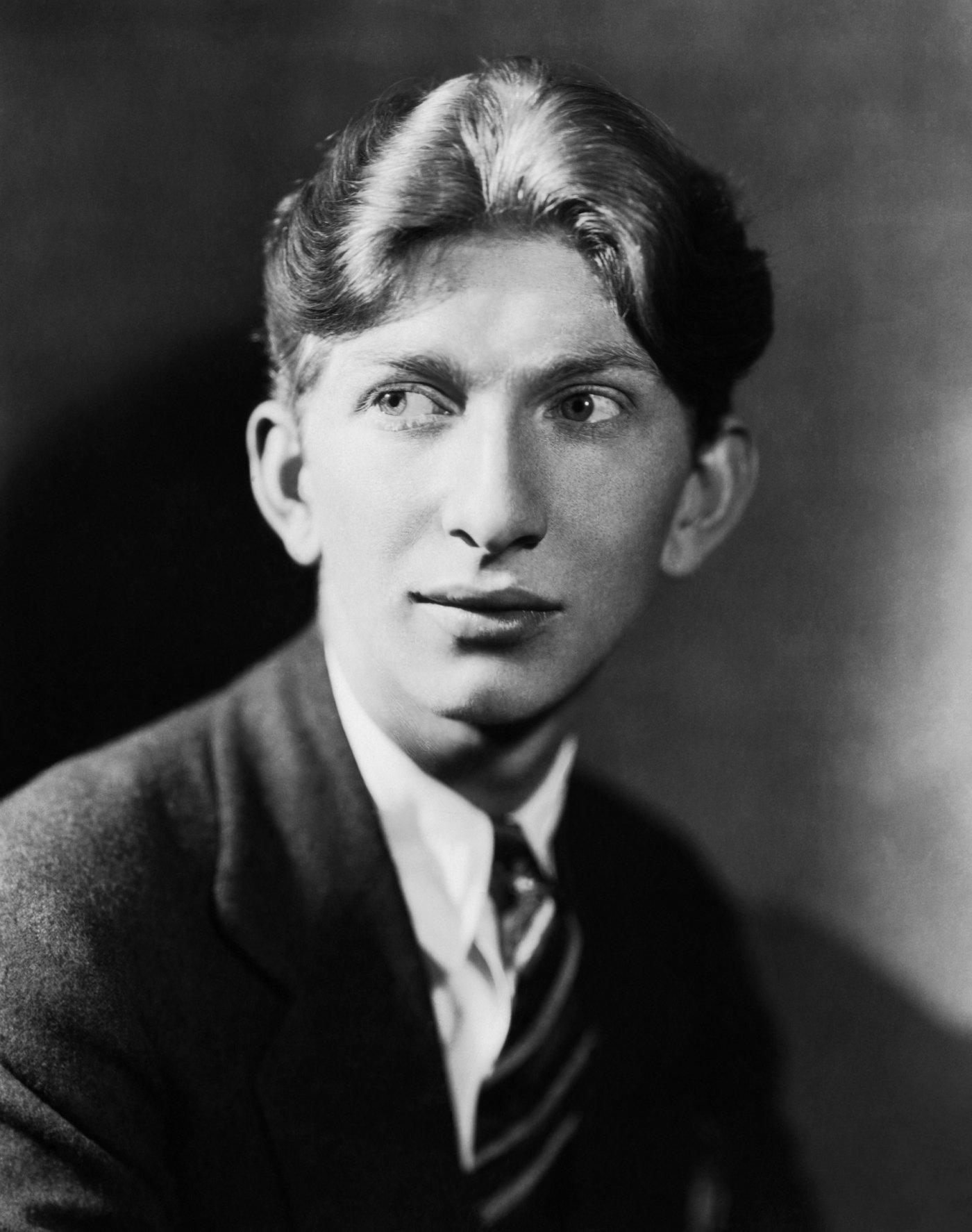

Depression Lessons

He possessed the sexual allure of a vegetable grown in poor light.

A cartoon version of Dust-Bowl produce, prematurely uprooted from the parched earth... Was this etiolated radish a batty answer to audiences in need—some unhinged nostrum for a nation suffering under otherwise incurable blues? Depression Lesson #12 argues Sterling Holloway (oh, yes!) delivered.

And he did so mainly by playing a miracle of employability.

No character actor embraced his inner schlump with such acquiescent sideways momentum, flung at a framed, highly realistic world of earnings by an invisible hand. His ample red pate and prodigious honker had more mass than his entire body, which resembled a crimped and wavering line, unsettled by the slightest vibration. The free enterprise system—holographic beyond the movie palace, tantalizingly real within it—gave Holloway's bellhops and cabbies the chance to mock our glimmering vision.

The Bankruptcy Barrel: A Historical Debate

In recent years I’ve been keeping an unofficial list of once-commonplace iconic images and tropes that seem to have vanished completely from the culture. A man on stilts, for instance, who was usually dressed like Uncle Sam. I can’t remember the last time I saw a man on stilts, or even heard a reference to stilts. Quicksand is another. Time was you couldn’t see a jungle adventure or a wacky comedy that didn’t at some point include a scene in which someone gets stuck in quicksand. For one reason or another, they’re no longer part of our collective consciousness.

Most recently I’ve become a little obsessed with barrel suits (also known as barrel cloaks, barrel shirts, or bankruptcy barrels). You know what I mean—an image of a destitute and naked man, a man who has quite literally and figuratively lost his shirt, who for lack of any other form of clothing has been forced to wear a wooden barrel held up by a pair of attached suspenders. If the subject in question was once very wealthy (i.e. someone who lost everything in the Crash), he might also be seen wearing a top hat. It used to be an inescapable representation of bankruptcy, appearing in countless animated shorts, political cartoons, and comedies.

It seems like such a ridiculous idea if you think about it. There are easier ways to keep oneself covered. A burlap sack, say. A potato sack would be so much easier to craft into a wearable form, and would be more comfortable and practical to boot. With a barrel you need to knock out the bottom, find a way to attach the suspenders, and even after all that’s done it remains impossible to sit down or move very fast while wearing it. There is absolutely nothing practical about a barrel suit. Yet it was the man in the barrel suit who came to immediately signal poverty.

The origins of the image are today a little mirky and the subject of some debate. While most people simply shrug their shoulders as to the origins of the barrel suit, a few intriguing educated guesses have been put forward.

Some trace it back to the 4th century B.C., when Diogenes, founder of the school of Cynical Philosophy, made a virtue of poverty and among his countless other pranks, chose to live in a barrel in the marketplace. It’s a tenuous connection, but perhaps the first historical example of a connection being drawn between poverty, barrels, and cynicism.

Certain European fairy tales from the 16th century include scenes in which, as punishment, drunkards and gamblers are placed naked into barrels and dragged through the streets behind a horse. Some other sources, apparently inspired by the fairy tales, claim the origin of the barrel suits exclusively the domain of unlucky gamblers. Having lost everything in a game of chance and with nothing left to bet, the other gamblers would place the unlucky man in a barrel and roll him into the street as a form of humiliation. The image of the man wearing a barrel eventually came to represent someone who had, again, lost his shirt while gambling. This notion, however, is mostly the result of armchair speculation.

More readily documented is the fact that in the 18th and 19th centuries, public drunkenness in England and Germany was occasionally punished by forcing the inebriate in question to wear a barrel in the town square, a form of degrading spectacle akin to the more sophisticated stocks.

The barrel as humiliating punishment seems to have made the leap across the Atlantic by the mid-19th century, as revealed in Miles O. Sherrill’s account of being a Union soldier held in a North Carolina prison during the Civil War.:

“While we were standing in the snow, hearing the abuse of Major Beal, some poor ragged Confederate prisoners were marched by with what was designated as barrel shirts, with the word "thief” written in large letters pasted on the back of each barrel, and a squad of little drummer boys following beating the drums. The mode of wearing the barrel shirts was to take an ordinary flour barrel, cut a hole through the bottom large enough for the head to go through, with arm-holes on the right and left, through which the arms were to be placed. This was put on the poor fellow, resting on his shoulders, his head and arms coming through as indicated above; thus they were made to march around for so many hours and so many days.“

And while the connection remains a little fuzzy, that, perhaps, might lead to the next and final jump. The origins of the barrel suit as a symbol of poverty are today generally traced back to Will B. Johnstone. In the 1920s and ‘30s, along with being a successful song lyricist (best known for “How Dry I Am”) and a writer for the Marx Brothers, Johnstone was also a popular political cartoonist for the New York World-Telegram. Among the regular cast of symbolic characters who appeared in his panel was The Taxpayer (the date of his debut is unknown), a naked man wearing a barrel to illustrate his penniless state. With the Great Depression, it’s not hard to see how The Taxpayer may have come more generally to represent the millions who had lost everything.

A Crisis of Passion

Making her Italian screen debut in Black Sunday in August 1960, Barbara Steele glowered into Mario Bava’s lens, and at that pivotal moment in cinema’s manic history something shone forth so ancient that even the most devout heretic experienced inchoate shivers of remorse. The mod summertime of the new decade was arrested, plunged backward, whereupon a strange, atavistic transformation occurred: the audience, pious enough to register shock at the intended effects, was nevertheless unprepared to confront the triumph of alchemy and necromancy over mere sackcloth and ashes. Shamefaced in the dark like Catholic schoolchildren remembering all they had been taught, the audience stared back at Steele’s eyes – a pair of druid’s eggs, bestowing true and everlasting illumination, as opposed to religion’s metaphorical kind – and shuddered inwardly at things no mere mortal could comprehend.

But what kind of “object” are we dealing with in Barbara Steele? Of course, the answer is partly grounded in Steele’s unique physical equipment – and here we’ll risk the cliché “otherworldly” to describe her famous emerald eyes. As if sparked to life by silent-film magician Segundo de Chomon, the supreme master of hand-tinted illusionism. Peculiar even within the context of gothic tales served up on celluloid, her eyes flash at us from well beyond the Gothic’s allotted time and place in history. Occasionally like a Victorian child molded from pellucid porcelain, and sometimes a skull with fleshy lips, eyes open and deep like two pits into the infinite. When the cameras are trained on her, they are not passive receivers recording visual information but deadly carbon-arc projectors probing the psychic crawlspaces where skittering impulses dwell.

There are eyes that photograph as soulful, as opposed to merely expressive—allowing the onlooker a glimpse into the funnel end of eternity. Think Robert Mitchum and Humphrey Bogart, whose eyes simultaneously invite and repel inquiry into the unwritten histories behind them. If the eyes are the windows of the soul, great movie stars are defenestrating their spirit essence right down the lens. Joan Crawford could scrub bathtubs merely by glancing at them. And that wonk-eyed Siamese sex cat, Karen Black, worried us with her revelation that some lazy eyes are less lazy than others.

Then there is Barbara Steele, whose famed peepers hint at the corrosive void that has replaced her soul. They offer a brief glimpse at the corrupted flesh beneath an unblemished alabaster encasement. Steele photographs like an imperious statue inwardly cursing all those who gaze upon it, as if some monument to classicism were startled into bitter sentience, or unwanted Keatsian fever. Her marble-white flesh remains an aesthetic plea for the proscenium arch's return to drama, and her columnar bearing and soaring height fused her to the monochrome of director Mario Bava's cursed pasteboard castles. This was the monster wrought by Italian genre horror: a theatrical form of the archaic. A wraith howling at a paper moon.

"Stars", unlike their thespian counterparts, do not need scripts or stories to thoroughly inhabit a motion picture. Histories without language, or even thought, flicker behind their eyes. Their presence – ineffable, diaphanous, seductive – provides the audience a beacon to follow to its only narrative conclusion. Outside the realm of this splendid cosmology, movies that rely on actors and 'acting', the common tools of theater, tend to miss the mark when metaphysics come into play.

As a visual form, Barbara Steele summons that occult universe – in this realm, she needs no interference from middleman auteurs. Her control of the camera’s gaze, like that of all movie stars worthy of the term, is primal and innately physical; an ancestral gift of bone structure handed down by prim Brits and soulful Portuguese peasants, and a sculptured riddle where good and evil join forces in somber disharmony. Her face becomes cinema's reawakening of an image which loomed large for 19th century Symbolists: The black star.

Warren William, Evil Capitalist Asshole

By all accounts, Warren William was a very quiet, reserved, and pleasant fellow. He was raised in a small town in Minnesota, he fought in World War I, and in his spare time he was an amateur inventor. He remained married to one woman his entire life.His career was never threatened by explosive drunken rampages at popular Hollywood nightspots or dark rumors of weekly bestial orgies at his mansion. In short, he was an incredibly boring man. Given the sort of nasty, raucous behavior on display we’ve come to think of when we think of pre-Code films, it hardly seems fitting that a man of William’s demeanor would ever come to be known as the King of the Pre-Codes, but there was a reason for that.

The pre-Code era offered up the usual motley parade of villainous types: killers, thieves, racketeers, two-bit chiselers, dirty cops, bought judges, sinister clergymen, run of the mill cheating husbands and wives, gold-diggers, and sleazy newspapermen, but to audiences of the times, there was one villain who trumped them all, who was in fact far more heinous and hateful than all those other namby-pamby ne’er-do-wells combined—The Businessman.

Depression Lessons #2

Zasu Pitts: All mien, a droopy bouquet self-sufficient in its droopiness, redolent of specific flowers. And yet, this lily of the valley knows it’s been brutally transplanted. Some actors do that, even if unconsciously—embody perfumed there-and-not-there presence, in this case a position within the general mayhem of pre-Code programmers that… yields. Gives way. There’s no sense of tragedy in her exodus from the exalted Silents to All Talking Pictures, not a hint of loss, in fact. Decaying sweetness comes with the schtick. At once defining and escaping capital "K" Kitsch, the Great Zasu’s trembling trademark vocalizations seem made for the coarsest ballyhoo, because, after all, doormats were suddenly IN! She evokes prettiness more than being pretty, and suggests, with her out-sized peepers and alabaster skin, Victorian ideas of purity so that her perennial status as a discarded, worn-out broom never fully takes hold. Is this a kind of victory? Today’s Depression Lesson comes to you in a one-liner about the stars of early Talkies: They weren’t necessarily pretty.

And not everyone tried fast-talking America out of The Great Depression. Some, like Zasu, lugged the burden of land-locked accents – congealed honey from a grocery in East Hell, Nebraska – onto Hollywood's synch-sound shores. Actually, she was raised by a one-legged father in Kansas. And came of age with a quavering alto honk pitched to the tremulous flutter of her hands.

by Daniel Riccuito