Without a Goal

“Wait a minute then,” people say, “what is their goal?”

And the benevolent questioner suppresses a shrug upon noting that there are young men refractory to the usages, laws and demands of current society, and who nevertheless don’t affirm a program.

“What do they hope for?”

If at least these nay-sayers without a credo had the excuse of being fanatics. And no, faith no longer wants to be blind. They discuss, they stumble, they search. Pitiful tactic! These skirmishers of the social battle, these flagless ones are so aberrant as to not proclaim that they have the formula for the universal panacea, the only one! Mangin had more wit…

“And I ask you: what they seeking for themselves?”

Let’s not even talk about it. They don’t seek mandates, positions or delegations of any kind. They aren’t candidates. Then what? Don’t make me laugh. They are held in the appropriate disdain, a disdain mixed with commiseration.

I too suffer from that underestimation.

There are a few of us who feel that we can barely glimpse the future truths.

Nothing attaches us to the past, but the future hasn’t yet become clear.

The Aspirations of All

What difference is there between anarchists and other men?

There is none!

In fact, take out a register and carry out an interesting survey: consult everyone around you about the reforms that should be carried out and you’ll find that they are all partisans of the suppression of either one or several laws.

When you’ve gathered together all these opinions, add up the sum of the suppressions of laws requested by each person and there will be nothing left to be done but to burn the penal code.

This is what the anarchists demand. They are the summation of the aspirations of all, the conclusion to the volume of reforms, and in carrying out this survey you will have written an anarchist book.

-Le Bandit du Nord, Roubaix, France. February 8, 1890

Translated by Mitchell Abidor

Ken Jacobs on “The Wizard of Oz”

Lecture: Ken Jacobs

Greetings to The Storefront Movie Tabernacle. Deacon Jacobs will read today, by light of laser, from MGM’s The Wizard of Oz. You are expected to sit up straight, and be models of rectitude and sobriety. Even as our hearts are melting we must put our minds to understanding how and to what purpose was this film designed to engage its Great Depression audience just as WW II was looming. And how is it, despite its clunky staginess, fevered mix of confession and disingenuousness, its muffled screaming mimis regarding sex – in this tale of sexual as well as economic impotence – and its dismissal of the desirability of democracy in an age of electric bullshit (for all the gumption its lead characters show), that it should remain myth-package supreme for Americans? Including that the official right-of-passage for every American kid is to keep eyes open when the flying monkeys attack. One explanation for its staying power (based on the belief that the Great Depression was only lightly built over, and the fault runneth deep) is that the movie promises… another movie next week. We can depend on the movies to be there. Dried up Miss Gulch may own the country but the movies will lift us free, over and over again.

by Ken Jacobs

Sunny Side Up

SUNNY SIDE UP 1929 STARRING JANET GAYNOR AND CHARLES FARRELL THE JOHN AND OLIVIA OF THEIR DAY IN THEIR FIRST TALKIE AFTER THEIR BOFFO HIT SEVENTH HEAVEN IN WHICH HE RETURNED TO THEIR SHABBY SEVENTH FLOOR WALKUP BLIND FROM THE WAR BUT THEN MIRACULOUSLY

The sleeping beauty awoke and spoke. Her thoughts and then some. Her delirious dreaming still came up in waves onto the sync-sound shore.

New at this she revealed more than she would. Her diction kept slipping exposing her regional and class feet of clay. We her devotees were touched and chilled by such mortal particularity. But she caught herself quick.

Hero of Our Nation

I first encountered Roger Ramjet on a Chicago public access station in 1983. It was part of an early morning show apparently aimed at stoner insomniacs. The show came on at five and also included episodes of Lancelot Link, Secret Chimp, that awful Beatles cartoon, and a weather report clarified by some appropriate pop song (“Here Comes the Sun” or “Here Comes the Rain Again”). I was usually up and around that early for some godforsaken reason, and originally started watching on account of Lancelot Link. Always did love that Lancelot Link. But Roger Ramjet was, well, let’s just say it was a revelation.

Zontar: The Thing from Venus

A study in microscopic paranoia, Zontar is one of the more outrageous products of mid-sixties UFO Fordism. Its roadkill ‘plot’ shoulders on Body Snatchers territory: An absurd papier-mache creature plans world domination by zombifying the Military Industrial Complex, beginning with a lonely SETI outpost in the Mojave. Most of the inaction takes place in clapboard rec-rooms, abutted to stock footage of missile silos and pans of a stark desert moonscape (the latter is actually a suburb of Dallas, according to the scholars). Inside their pre-fab hells, the inmates mix drinks and threaten each other, occasionally erupt in spasms of wild emotion, then settle down again to the demands of stage-bound budgeting and the confines of a constant medium-shot frame. In a performance that must have been deeply influenced by Milgram’s torture experiments, Tony Huston is especially manic and perplexing as Zontar’s first human dupe, a NASA egghead called Keith. There are hints of a deep-seated nihilism behind his near-hysteria, but seeing that he also wrote the script, maybe it’s just the glee of a strange and lonely pride. His foil is John Agar, an actor who always seems to take on the attributes of the furniture around him. He is a practitioner of Taoist wu, the necessity of presence – neither more nor less.

Zontar finally arrives on earth and sets up command and control in a cave, where he cuts a touchingly vulnerable figure. As he is quite immobile – perhaps because Agar’s salary ate up most of the budget – he is assisted by strange airborne skeet-creatures who zombify the local servicemen and townspeople by stinging them. Repetitive shots of these cardboard demons flying over telephone wires, suburban bungalows, and stalled trucks look like captures of today’s drones haunted-up in memorial black and white. This is indeed skeletal filmmaking at the margin of afternoon fever-dreams, and it has a genuinely purgatorial atmosphere of cramp and marginal reality. Zontar of Venus looks splendid: a Duk-Duk fetish, proud and pitiful in glaring fabrication and bad lighting, an abandoned nightmare decaying in front of overgrown children, waiting for the end like a Mormon angel.

Huston soon realizes that Zontar is an intergalactic fascist whose plans are not liberation but human slavery. In a climax more desperate than thrilling, he rids the universe of both Zontar and himself with something called ‘plutonium ruby crystal’ – yet one feels a terrible certainty that the ‘story’ will repeat in a never-ending informational loop. The living and the dead will again assume their places and carry out their tasks once more, until the last flickering of recorded time. This sense of cyclical production is perhaps the ghostly product of Zontar’s eternal run on rosy-hour TV for the last half–century, as if the film itself had taken on the substance of its own interminable repetition. Zontar is cousin to Milstar.

Trauma-Toons

A shortish documentary called Cartoon College, directed by Josh Melrod and Tara Wray, celebrating the Center for Cartoon Studies in Vermont, left me thinking about a bunch related or semi-related things. The (unaccredited) Center offers a two-year course leading to a Master of Fine Arts in cartooning.

First of all, is such a curriculum necessary? In the applied-arts sense, probably not really, but as a supportive place for artists doing something that, the film proclaims, society at best ignores, or at worst sneers at, it shines. Kids and adults – including a man in his late 60s – act as though they are finally being allowed to crawl out from under the carpet.

Which by the end made me uneasy. The presumably self-selecting group projects a stereotype of cartoonists as universally depressed dweebs with godawful childhoods – salvaged suicides or serial killers in waiting. Somehow, I can’t believe this is a broadly accurate cross-section of those involved in an admittedly wacky profession.

Which then led me to recall how much the newspaper comics meant to me growing up, and to a lot of kids of that era. And it wasn’t just kids reading the “funnies”; consider the sophistication and orientation of “Winnie Winkle,” “Brenda Star,” “Rex Morgan” – these were works written with an adult audience first and foremost in mind.

They were the static YouTube of the time, and their hold on me has never relaxed. Will Eisner and his seven-page Sunday adventure "The Spirit" were the highlight of my week. In the ‘70s, Eisner’s boundary-breaking foray into the “graphic novel” made my liver quiver.

The Wet Parts of the Face

Sometimes, watching a movie while insufficiently awake, random, inept idiocies will pop into my forethought: “They’re not socially distancing!” while looking at a crowd scene in a twenties slapstick short. “He shouldn’t stand so close to them when he’s talking,” during a three-handed dialogue crush in a Warners precode. It’s become second nature (which is no nature at all), this omnipresent anxiety about proximity. How will it feel when (I assume there’s going to be a “when”) I get back into the cinema.

Heavy

Long before his face became familiar to television audiences as the obese star of the long-running cop series Cannon, and long after his voice had become familiar to radio audiences as the star of everything from The Lone Ranger and Suspense to Gunsmoke and Buck Rogers, William Conrad was a busy character actor in films, bridging his earlier and later heroic roles by playing a string of killers, corrupt city officials, gangsters, and cowardly busboys, many of them uncredited, most offering him only a few brief moments of screen time, and all of them hard to forget. His smooth corpulence, thick mustache, toadish features, and resonant voice gave him a presence that made playing heavies all but an inevitability when Conrad moved from radio to screen. It also helps explain why a radio star of his magnitude (his voice was as recognizable to the masses as Orson Welles’) would be given such small roles when he made the leap. But the former WWII fighter pilot made the most of them.

The Mysterious Death of a Hollywood Director

This is the tale of a very famous Hollywood mogul and a not-so-famous movie director. In May of 1933 they embarked together on a hunting trip to Canada, but only one of them came back alive. It’s an unusual tale with an uncertain ending, and to the best of my knowledge it’s never been told before.

I. The Mogul

When we consider the factors that enabled the Hollywood studio system to work as well as it did during its peak years, circa 1920 to 1950, we begin with the moguls, those larger-than-life studio chieftains who were the true stars on their respective lots. They were tough, shrewd, vital, and hard working men. Most were Jewish, first- or second-generation immigrants from Europe or Russia; physically on the small side but nonetheless formidable and – no small thing – adaptable. Despite constant evolution in popular culture, technology, and political and economic conditions in their industry and the outside world, most of the moguls who made their way to the top during the silent era held onto their power and wielded it for decades. Their names are still familiar: Zukor, Goldwyn, Mayer, Jack Warner and his brothers, and a few more. And of course, Darryl F. Zanuck. In many ways Zanuck personified the common image of the Hollywood mogul. He was an energetic, cigar-chewing, polo mallet-swinging bantam of a man, largely self-educated, with a keen aptitude for screen storytelling and a well-honed sense of what the public wanted to see. Like Charlie Chaplin he was widely assumed to be Jewish, and also like Chaplin he was not, but in every other respect Zanuck was the very embodiment of the dynamic, supremely confident Hollywood showman.

In the mid-1920s he got a job as a screenwriter at Warner Brothers, at a time when that studio was still something of a podunk operation. The young man succeeded on a grand scale, and was head of production before he was 30 years old. Ironically, the classic Warners house style, i.e. clipped, topical, and earthy, often dark and sometimes grimly funny, as in such iconic films as The Public Enemy, I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang, and 42nd Street, was established not by Jack, Harry, Sam, or Albert Warner, but by Darryl Zanuck, who was the driving force behind those hits and many others from the crucial early talkie period. He played a key role in launching the gangster cycle and a new wave of sassy show biz musicals. At some point during 1932-33, however, Zanuck realized he would never rise above his status as Jack Warner’s right-hand man and run the studio, no matter how successful his projects proved to be, because of two insurmountable obstacles: 1) his name was not Warner, and 2) he was a Gentile. Therefore, in order to achieve complete autonomy, Zanuck concluded that he would have to start his own company.

In mid-April of 1933 he picked a public fight with Jack Warner over a staff salary issue, then abruptly resigned. Next, he turned his attention to setting up a company in partnership with veteran producer Joseph Schenck, who was able to raise sufficient funds to launch the new concern. And then, Zanuck invited several associates from Warner Brothers to accompany him on an extended hunting trip in Canada.

Larger than Life

In 1927, Albert Bertanzetti and his three-year-old son, William, were taking a stroll when they stopped to join a small crowd watching a film being shot on the streets of Los Angeles. During a break in the shoot, Albert suggested his son go show the director, Jules White, his little trick. So William toddled over to White and tugged on his pant leg. When he had White’s attention, William flipped over, went into a headstand and began spinning in circles. White was so taken with the trick he gave the young Bertanzetti a small uncredited role in the two-reel short, Wedded Blisters. Afterward, William earned a regular role in the popular Mickey McGuire series of shorts, where he played Mickey Rooney’s younger brother Billy. Taking prevailing anti-Italian sentiments into consideration, in the credits he was cited as “Billy Barty.”

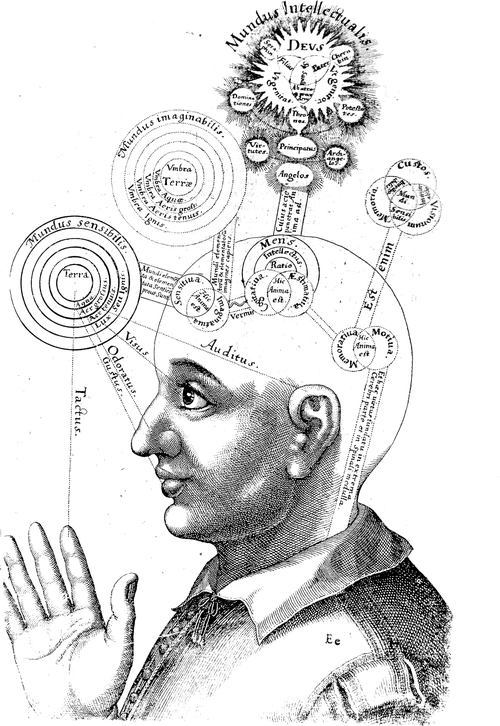

A Dodderer Looks at His Brain

When I’m out walking in our wonderful woods, I keep my head down because otherwise I’ll stumble over every rock, no matter how familiar the path. I don’t know what my feet will do next.

If I wander a few yards off the path to check out a fallen tree, then swivel slightly sideways, I’m disoriented for the first few seconds. I have no learned sense of direction.

Driving, I can’t accurately locate a knob on the dashboard. I have to feel for it or (worse) look. My body does not learn from repeated positioning. I have little of what’s now called “muscle memory.”

I have double vision and little depth perception. I can’t lay a clean line of wallboard joint compound because it requires the ability to accurately estimate a 1/8 inch-thick coating. In the kitchen, I’ll reach for a knife on the magnetic rack and slam my hand into the wall. I lumber into doorways.

Years ago, a 13-year-old housemate in our commune, one of the most extended people I’ve ever known, described her mentally precocious younger brother as “physically stupid.” That fired all sorts of slumbering neurons in my head and has stuck with me ever since. It was a brilliant observation.