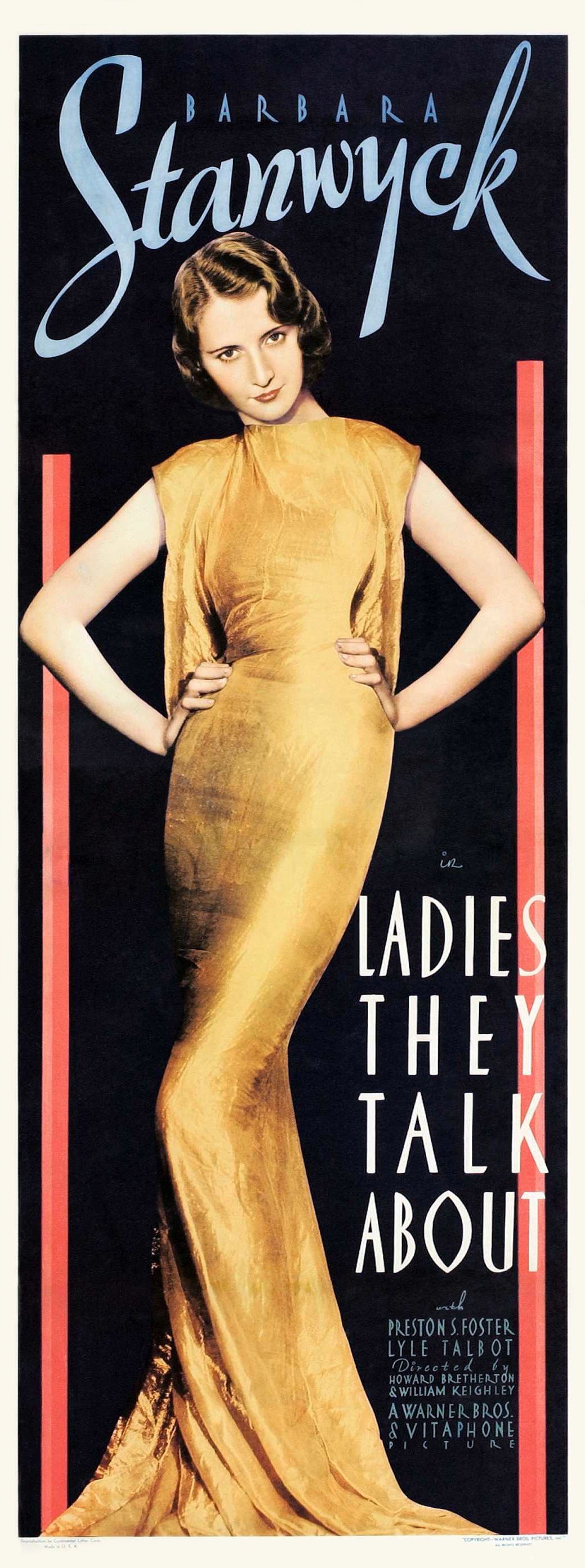

Ladies They Talk About

Who knew prison was this much fun? On a typical night in the women’s ward at San Quentin, a society dame who put ground glass in a rival’s soup cuddles her Pekingese; a madam reminisces about the “beauty parlor” she used to run; and a creepy religious fanatic dons black lingerie to listen to her idol, a radio evangelist. Meanwhile, the bubbly Lillian Roth croons, “If I Could Be With You” to a photo of…Joe E. Brown, and a cigar-smoking lesbian (“Watch out for her, she likes to wrestle,” a new inmate is warned) does weight-lifting exercises. This is less a jail than a clubhouse for deviant gals. Remorse? Repentance? Don’t make them laugh.

Especially not Barbara Stanwyck, a glamorous bank robber doing two to five for her role in a heist. Sardonic, jaded and immune to sentiment, she saunters around the hoosegow chewing gum and handing out stinging put-downs. A straight-arrow reformer (the object of the religious fanatic’s crush, and the human equivalent of a bowl of tapioca pudding) falls hard for Stanwyck and pursues her adoringly—even after she shoots him in the arm. This pairing of a bad girl and a virtuous male redeemer is a welcome reversal of the usual trope. The greatest gulf between pre-Code and film noir is that the former is so tolerant, and the latter so punitive toward women who break the rules. Like defense attorneys, these movies argue that the ladies’ circumstances should be taken into account: the toughness of their world, their limited options. And from the witness stand they use everything they’ve got: anger, tears, wisecracks and killer gams. What jury would find them guilty?

by Imogen Sara Smith

All the World’s a Stage

In 1988, a socio-linguist at the university of Pennsylvania posted a note on the departmental bulletin board announcing she had moved her late husband’s personal library into an unused office. Anyone who wanted any of the books should feel free to take them. Her husband had been the chair of Penn’s sociology department. They’d married in 1981, and he died the following year at age sixty. Normally you’d expect the books and papers to be donated to some library to assist future researchers, but she’d recently remarried, so I guess she either wanted to get rid of any reminders of her previous husband, or simply needed the space.

At the time my then-wife was a grad student in Penn’s linguistics department, and told me about the announcement when she got home that afternoon.

Well, had this professor’s dead husband been any plain, boring old sociologist, I wouldn’t have thought much about it, but given her dead husband was Erving Goffman, I immediately began gathering all the boxes and bags I could find. That night around ten, when she was certain the department would be pretty empty, my then-wife and I snuck back to Penn under cover of darkness and I absconded with Erving Goffman’s personal library. Didn’t even look at titles—just grabbed up armloads of books and tossed them into boxes to carry away.

As I began sorting through them in the following days, I of course discovered the expected sociology, anthropology and psychology textbooks, anthologies and journals, as well as first editions of all of Goffman’s own books, each featuring his identifying signature (in pencil) in the upper right hand corner of the title page. But those didn’t make up the bulk of my haul.

There were Catholic marriage manuals from the Fifties, dozens of volumes (both academic and popular) about sexual deviance, a whole bunch of books about juvenile delinquency with titles like Wayward Youth and The Violent Gang, several issues of Corrections (a quarterly journal aimed at prison wardens), a lot of original crime pulps from the Forties and Fifties, avant-garde literary novels, a medical book about skin diseases, some books about religious cults (particularly Jim Jones’ Peoples Temple), a first edition of Michael Lesy’s Wisconsin Death Trip, and So many other unexpected gems. It was, as I’d hoped, an oddball collection that offered a bit of insight into Goffman’s work and thinking.

Against Organization

We cannot conceive that anarchists establish points to follow systemically as fixed dogmas. Because, even if a uniformity of views on the general lines of tactics to follow is assumed, these tactics are carried out in a hundred different forms of applications, with a thousand varying particulars.

Therefore, we don’t want tactical programs, and consequently we don’t want organization. Having established the aim, the goal to which we hold, we leave every anarchist free to choose from the means that his sense, his education, his temperament, his fighting spirit suggest to him as best. We don’t form fixed programs and we don’t form small or great parties. But we come together spontaneously, and not with permanent criteria, according to momentary affinities for a specific purpose, and we constantly change these groups as soon as the purpose for which we had associated ceases to be, and other aims and needs arise and develop in us and push us to seek new collaborators, people who think as we do in the specific circumstance.

When any of us no longer preoccupies himself with creating a fictitious movement of individual sympathizers and those weak of conscience, but rather creates an active ferment of ideas that makes one think, like blows from a whip, he often hears his friends respond that for many years they have been accustomed to another method of struggle, or that he is an individualist, or a pure theoretician of anarchism.

It is not true that we are individualists if one tries to define this word in terms of isolating elements, shunning any association within the social community, and supposing that the individual could be sufficient to himself. But ourselves supporting the development of the free initiatives of the individual, where is the anarchist that does not want to be guilty of this kind of individualism? If the anarchist is one who aspires to emancipation from every form of moral and material authority, how could he not agree that the affirmation of one’s individuality, free from all obligations and external authoritarian influence, is utterly benevolent, is the surest indication of anarchist consciousness? Nor are we pure theoreticians because we believe in the efficacy of the idea, more than in that of the individual. How are actions decided, if not through thought? Now, producing and sustaining a movement of ideas is, for us, the most effective means for determining the flow of anarchist actions, both in practical struggle and in the struggle for the realization of the ideal.

Sabotage

Emile Pouget (1860-1931) spent his political life on the revolutionary syndicalist wing of the French working-class movement. Never frightened of revolutionary violence, he was arrested in 1883 and spent three years in prison for a riot that resulted in the pillaging of three bakeries (a riot at which Louise Michel was also arrested) . He was most famous for his newspaper and almanac called Le Père Peinard, which advocated not just syndicalism, but direct action by the workers, principally in the form of sabotage, which he was even able to get the Confédération Générale du Travail to adopt as an officially sanctioned tactic. This article is from the 1898 edition of his almanac.

'“A Tough Guy, Eh?”

We tolerate Chester Morris. I don’t know that we love him.

Part of the problem is that the golden age of pre-code cinema for Morris is also the golden age for Jimmy Cagney, William Powell, Warren William, actors who sparkle with wit, agility, charm, energy, qualities poor Chester can approximate but never truly own. At this time, Clark Gable is not yet King of Hollywood, but he’s got something: a kind of gangling, lupine, on-the-make gusto. Bogart’s glory days are still ahead of him too, but at least they arrived: Morris sank further into B-movie territory, and not even good B’s, mostly. Have you ever tried to watch one of those Boston Blackie films? They had Robert Florey, Edward Dmytryk, and Budd Boetticher as directors, but any charm or personality those luminaries channelled towards the films got sucked down the Morris charisma funnel. Latterly, Boston Blackie was all that Morris did, and he wasn’t even very good at it.

Homage to the Gods (and Their Offspring)

Children of Paradise (Les Enfants du Paradis) has a strange, convoluted production history, and a somewhat strange history with me personally.

Directed by Marcel Carné in 1943-44 in occupied France—actually, under the Vichy puppet government—it was the victim of German and Vichy antagonism, bureaucratic limitations, anti-Semitic laws, natural disasters and, as a result, protracted delays in production.

Exactly how Carné and company could put together a 19th-centuiry costume drama involving 1,800 extras and running twice as long as “permitted” by Vichy dictat has never been totally clear. How amazing, then, that it emerged as one of the monuments of movie-making.

The first time I saw Children of Paradise I hated it. I sat bored for two hours in the auditorium of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Anthropology and Archaeology watching a disconnected bunch of declamatory larruping about actors and mimes in 1830s Paris. So why on earth did I go back to see the uncut version, running over three hours? It defies justification, but I thank my peculiar instinct, because I’m a better person for it.

The original version runs 190 minutes, and it builds emotionally during every minute. Despite the lavish setting, it is wholly a movie of character, detailing every form of human interaction imaginable. As a wracking document of love and obsession, it has no equal I know of.

The milieu is the theater district of Paris in the1830s, especially the Funambules theater along the “Boulevard du Crime,” where pickpockets and conmen ply their trade amongst the pulsating throngs. “Paradise” refers to “the gods,” the high, cheap seats of the lower classes, to which the actors, their children, paid theatrical homage.

Supposedly, the incident that inspired the story line was the bludgeoning of an old-clothes seller by a mime, an inexplicable act that Carné and screenwriter Jacques Prévert hoped to illuminate. To do that….

Garance (“comme la fleur”), played by the single-named Arletty, floats through life on a raft of boredom, blown by some unattainability within, magnetizing men in part through her beauty, but more through the unfathomable mystery of who she is and why. She becomes the focus of a convoluted love pentangle, sought, semi-possessed, but never won by four men:

Baptiste the mime (Jean-Louis Barrault), unfaltering in his adoration, which is returned by Garance in equal measure—but at an agonizing distance.

Frédérick Lemaître the actor, who takes her body as lover for a time but can never reach her soul.

Comte Édouard de Montray, a loathsome aristocrat who uses his position to ensnare Garance as his mistress.

Lacenaire, the brilliant, egomaniacal criminal entrepreneur, a man without scruples yet an odd, undeviating honesty of person.

Baptiste, Lemaître and Lacenaire were historical figures. Montray was closely based on another. Though all that is hardly important. What gives the movie its extraordinary depth is that these four characters (along with Garance) embrace virtually every human emotion, motivation, and range of moral and ethical involvement.

Starting with the most admirable, Baptiste loves Garance with a passion that almost devours him, yet he treats both his rivals and Nathalie, his wife, with a consideration that is almost as lethal to him as his devotion to Garance.

Lemaître is driven by ambition that enflames and ennobles his acting even as it blinds him to his own limitations. He and Baptiste remain true to each other; when, at last, Lemaître realizes that he has no hope of overcoming Garance’s love for Baptiste, he thanks Baptiste because, “Now I can play Othello.”

Montray, arrogant as much by nature as position, feels no compunction in using Garance for his own ends. The acme of upperclass worthlessness, he deems whatever he does right simply because he does it.

Lacenaire: Ah, Lacenaire is one of the most remarkable characters ever put on film. A boundless cynic with no moral base, he treats crime as a commodity, openly boasting that no one outside himself matters, no one influences his actions or limits his reach. All of humanity is open to his grasp, and he refuses pointblank to deal on any terms but his own. Challenged to a duel by Montray, he answers, “Absolutement pas!” for only he will choose the time and place to administer justice. He could easily be branded a sociopath, and yet… while perhaps fully believing his denial, he loves Garance as tormentedly as the others, and he it is who gives his life for her, stabbing Montray in a Turkish bath, then calmly waiting for arrest and the guillotine.

Carné proves himself an actors’ director, for each of these conflicted, tortured souls is fully inhabited:

Arletty as Garance is letter-perfect. Never flirting, seldom fully engaged, making no effort to attain what she gains so easily but does not value, she smiles with easy grace but seems neither content nor disillusioned. She knows instinctively that whatever it is she might want cannot be had. The world washes over her but never cleanses.

Barrault’s Baptiste radiates an unforgettable beauty—small, slim, tight as a watchspring offstage, as the mime he projects a sinuous delicacy that avoids the maudlin (of the same school as Marcel Marceau, he projects Marcel’s simple grace, economy of movement and unerring choice of telling detail, without, as was too often the case with Marceau, that underlying whiff of the effete).

Pierre Brasseur keeps Lemaître charming even when most self-involved, a rake with blunted teeth who wallows in his own emotions, from the sublime to the mawkish. The perfect loose companion, yet the worst sort of cohabiter.

Lacenaire could not have been realized without the eviscerating intensity of Marcel Herrand. Never does this magnificently coifed symbol of inhumanity step outside his self-concern, yet the something—that something underneath still radiates.

Everything rests on the superb screenplay by Prévert. Both before and after, he collaborated on several films with Carné, but this was his culmination. The dialogue, like the filming itself, is a distillation of emotions. The characters claw at each other’s innards—though far more often at their own—without descending into melodrama. They speak from the heart even when taking the greatest pains to disguise their spirit.

I have the English translation of the full screenplay from 1967, part of a wonderful series of “Classic Film Scripts” put out by Simon and Schuster and, like everything else, now out of print. It includes every word of the final version, including those scenes cut in editing. What amazes me: No matter how simple or complicated the scene, the decision to cut was correct. The very last scene to be removed, during the wrenching ending, was the death of the ragman that had set the script in motion.

Is this my favorite movie of all time? Yes. Close second in the “epic” realm: Seven Samurai. I’m sure it’s hard to imagine how a three-hour movie can be the epitome of tight, cut-to-the-bone editing, but I think that’s the case with Children of Paradise.

by Derek Davis

The Cruller

I had a date but I was much too early. There was a coffee shop across the street where I could sit at a counter and have a cup of coffee.

Love Bug

Filmmaker and film fan Jean-Pierre Melville, with his thick accent, pronounced the name Fronk McHyoog. Which somehow feels right.

A Dream

After a long walk I find myself in a third class compartment, where there are other travelers I can barely make out. Just as I’m about to fall asleep I notice that the regular jolts of the train are chanting a word, always the same one, and which is more or less “Adéphaude.” The “adéphaude” is a precious yellow stone that I see sitting in the mesh bag next to a poorly wrapped package, enveloped in wrapping fabric with a railroad label on it bearing the inscription “Rhodes 1415,” which I am convinced is an error. It is impossible for me to place the battle in question despite the basket weavers I question one after the other along the interminable marsh I am crossing with the air of a vagabond. I have arrived at a second class wagon. I sardonically make the observation that there are now in the mesh bag two packages bearing the mention “Rhodes no date.” At that moment I notice in the opposite corner a young woman who is speaking agitatedly to a companion who is at first invisible and who could be me, or some distant relative of a certain Lady Carnegie who I think I knew when I was young. The young lady is dressed with great elegance. I am only able to make out a few words of conversation: “…lacking lacquer…” It is obviously a question of the packages which, in fact, look extraordinarily scaly. I turn my eyes towards the lady’s interlocutor and I see that he is covered in armor, which completely hides him. I stand up, indignant. At my feet are the remains of a cold meal. The lady wipes her hands with a lace handkerchief. We are in the middle of the countryside, near an embankment. It’s the evening of the battle of Marignan.

by Louis Aragon

La Révolution Surréaliste, 3 yr, No. 9-10, October 1927

Translated by Mitchell Abidor

What is an Anarchist?

A chaos of beings, of acts and ideas; a disordered, bitter, merciless struggle; a perpetual lie, a blindly spinning wheel, one day placing someone at the pinnacle, and the next day crushing him: these are just a few of the images that depict current society, if it were possible for it to be depicted. The brush of the greatest of painters and the pen of the greatest of writers would splinter like glass if we were to employ them to express even a distant echo of the tumult and melee that the is depicted by the clash of appetites, aspirations, hatreds and devotions that collide and mix together the different categories among which men are parceled out.

NAFTA

Dear Daniel – As to citing NAFTA as one of Bill Clinton’s accomplishments: shortly after it was passed I was down in Chihuahua, my wife’s home town, and her rich relatives were all licking their chops in anticipation of making millions. When I ventured to express a mild skepticism these charmingly polite people were suspicious that my wife had married a Communist.

One of the many results of NAFTA was to drive the small Mexican farmer off his land (Milpa) and the Ejidos, communal farms which go back before the Conquest, by flooding the market with cheap subsidized American corn. Now when they are starving and have no recourse but to try to get into the States, we brutally try to build a fence to keep them out and patrol it with moronic vigilantes. “Illegal Immigration” becomes a hot political issue and none of our brainless candidates has any real answer other than to whip up hysteria.

Chihuahua was a small provincial city at the foot of the Sierra Madre. They used to kid themselves as being a “rancho,” small farm. It has a glorious history as the cradle (La Cuna) of the Mexican Revolution. Pancho Villa, Felipe Angeles, the mighty Division del Norte which won the big battles of the Revolution. My wife’s Grandparents, Leonardo and Dolores Revilla, were figures in the Revolution, friends and associates of Abraham Gonzales, great revolutionary Governor of Chihuahua, and General Felipe Angeles, the cleanest figure (la Figura mas Limpia) in the Revolution. When General Angeles was executed by the counter revolutionary Carrancistas, my wife’s Grandmother and Mother, Carmen Revilla, were with him in his last moments. My youngest son Philip is named for him. Dona Dolores Revilla founded the first Feminist club in Chihuahua. Later she was honored by the Government for her “Many acts of humanity” during the Revolution. She is also pictured in a mural in the Municipal Palace, right between Pancho Villa and Abraham Gonzalez.

Now that valiant city is riddled by the drug traffic. Mainly because Americans can’t refrain from shoving stuff up their noses and selling assault rifles to the cartels. I still have relatives down there and they are suffering. As was said over a hundred years ago, “Poor Mexico, so far from God, so close to the United States."

But as to Clinton’s being the worst President, he is up against a very strong field. We cannot pass over George W. Bush who, as they say, needs no introduction, and Ronald Reagan who to my mind began the cycle of destruction. Before him the American way had been, sure the big guys got theirs, but they always left a little for us. It was under Reagan that the "we want it all” cycle began. Besides repeal of Glass-Steagal, engineered by the all-wise Rubin which is a prime mover in the current debacle – Rubin is still very much in the scene as the eminence grise behind Summers and Geithner – we must add “Welfare Reform” which ended “Welfare as we know it” to the list of Clinton’s accomplishments.

Letter from Roy Metcalf

Lost Lyrics to “The Big Rock Candy Mountain”

The punk rolled up his big blue eyes

And said to the jocker, “Sandy,

I’ve hiked and hiked and wandered too,

But I ain’t seen any candy.

I’ve hiked and hiked till my feet are sore

And I’ll be damned if I hike any more

To be buggered sore like a hobo’s whore

In the Big Rock Candy Mountains.”