Miznerisms

“Never joke with a fool.”

“Why do women reformers almost always worry about men?”

“Most hard-boiled people are half-baked.”

“I respect faith, but doubt is what gets you an education.”

“The cuckoo who is onto himself is half way out of the clock.”

“I can usually judge a fellow by what he laughs at."

"Easy Street is a blind alley.”

“The only bird that gives the poor a real tumble is the stork.”

“I hope to heaven I never become so genteel that I can handle my amusement with a smile. For me there is literally no gift to compare with a genuine belly laugh.”

“The best way to keep your friends is not to give them away.”

“Henry Ford is a conservative man but he has done more for romance in America than any other individual. And for acrobatics."

-Wilson Mizner (1876-1933)

Not Broke But Not Flush: “Dust Be My Destiny”

Jerome Odlum was what you might call a bit of a crusader. He was a newspaper editor in the ‘20s and ‘30s who went on to become a successful novelist and short story writer. Drawing from his newspaper background, most of his books dealt with crime and the corruption of the criminal justice system. His novel Each Dawn I Die caused such a stir that it led to major prison reforms nationwide and was subsequently turned into a popular film. Even if he was a little heavy-handed, he got his point across.

A number of his books and stories went on to become films including, in 1939, Dust Be My Destiny, which focused on the treatment tramps and hobos could expect at the hands of the Law.

Hollywood dealt with the social and political ramifications of the Depression in a number of ways. Some directors played it for laughs, not to make light of the desperate realities, but instead to try and stave off the despair for a few hours. Others, like Wild Bill Wellman, subtly (and sometimes not so much) seemed to call for anarchist rebellion. Still others—as in Gabriel Over the White House and Night Beat—dreamed of a strong fascist leader who would march us all in lockstep out of the mess.

The call in Lewis Seiler’s film version of Dust Be My Destiny is a little quieter and simpler than all that. It asks that the nation return to its founding principles, and that justice be handed down the same to everyone, no matter how much money they have or what part of the train they ride in..

Now in his seventh film, John Garfield stars as Joe Bell. As the film opens, he’s being released from prison after serving a year and a half for a robbery he didn’t commit. He and a friend hop a freight heading anywhere, Joe is understandably bitter after his experience. “Nobody gives breaks to guys like us,” he says. He’d spent much of his life on the move and hopping trains, so he knew how hoboes were treated. And sure enough a railroad bull busts him for vagrancy and sends him to a work farm. There he falls for Mabel (Priscilla Lane), who happens to be the foreman’s step daughter. After getting into a fight with the foreman, Joe and Mabel run away and get married. Moments after becoming newlyweds they become fugitives as well, after learning that the foreman died and an arrest warrant has been issued for Joe. They both know he’s innocent and Mabel encourages him to turn himself in, but he’s previous experiences tells him this would be pointless—he’d still be looking at the gallows.

Elsa Lanchester: Catalogue Woman

In the prologue to James Whale’s The Bride of Frankenstein (1935), Elsa Lanchester plays Mary Shelley, sitting and sewing as Byron (Gavin Gordon) and her husband Percy (Douglas Walton) look on. “She is an angel,” Byron says, and Mary rejoins, “You think so?” with a devilish smile. There is a storm going on outside. “You know how lightning alarms me,” she purrs, humorously, for Mary, like Lanchester herself, loves nothing more than a storm. Lanchester, with her Gothic, serrated prettiness, plays this prologue poised on the very edge of camp. “It’s a perfect night for mystery and horror,” she says. “The air itself is filled with monsters.”

“She’s alive! Alive!” cries Colin Clive’s Dr. Frankenstein at the end of this classic horror film, with all of its allegorical insights into being an outsider and all of its stylish humor. We see the Bride’s eyes first in close-up, and when her bandages are taken off, Lanchester stands before us in a flowing white gown with her wavy hair sticking up on end. Does the fabulously queeny Dr. Pretorious (Ernest Thesiger) tease the Bride’s hair like this for her?

US and Israel: Is the ‘Unbreakable Bond’ Finally Breaking?

Israeli President Isaac Herzog added nothing of great value in his speech at the United States Congress on July 19.

His was the typical language. He spoke of a ‘sacred bond’, touted the shared experience between both nations as “unique in scope and quality”, and celebrated the great, common “values that reach across generations”.

But this theatrical language was meant to hide an uncomfortable truth: the relationship between Israel and the US is changing at a fundamental level.

Two days before Herzog’s speech, Israel’s opposition leader and former prime minister, Yair Lapid, declared that “the United States is no longer (Israel’s) closest ally.”

Lapid’s words were a mix of facts and political opportunism.

Lapid and others in his camp are keen on blaming Israeli Prime Minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, for the waning relationship between both countries; or to use more pertinent language, for weakening the ‘sacred’, ‘unbreakable bond’, which has for many years joined the two countries together.

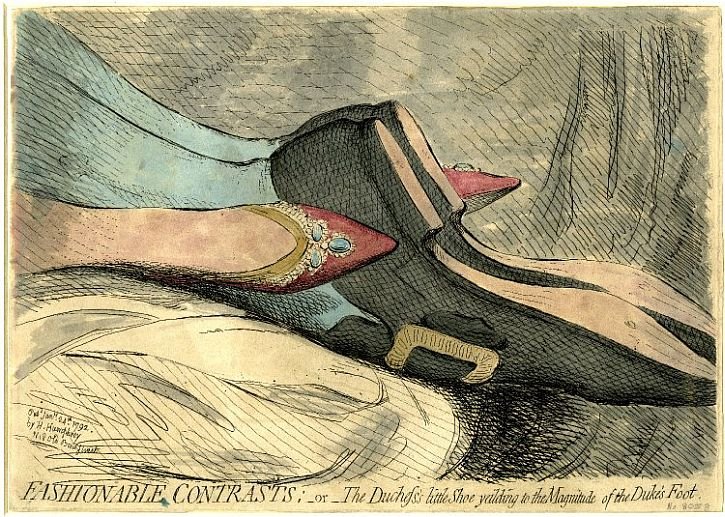

Vulgar Tongue

It’s not really necessary to sing the praises of Francis Grose’s 1785 Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue (“Buckish Slang and Pickpocket Eloquence,” as my edition subtitles it). Simply to quote from it ought to be enough, so here goes. Filthy, grotesque and brutally incorrect, it’s nevertheless a defiantly vital argot, which is more than can now be said for anybody who ever spoke it.

ANABAPTST: a pick-pocket caught in the fact, and punished with the discipline of the pump or horse-pond.

BUCKINGER’S BOOT: The monosyllable.* Matthew Buckinger was born without hands and legs, notwithstanding which he drew coats of arms very neatly, and could write the Lord’s Prayer within the compass of a shilling; he was married to a tall handsome woman, and traversed the country, shewing himself for money.

CLAP. A venereal taint. He went out by Had’em, and came round by Clapham home; i.e. he went out wenching, and got a clap.

Leon Czolgosz: May His Memory Be a Blessing

In Paris on December 9, 1893 the anarchist Auguste Vaillant tossed a bomb from the visitor’s gallery onto the floor of the Chamber of Deputies. Twenty people were wounded, and none killed. Despite there being no deaths, Vaillant was executed on February 3, 1894. (May his memory be a blessing).

In Lyon on June 24, 1894 the anarchist Santo Caserio stabbed to death Sadi Carnot, the president of France and grandson of the Revolutionary regicide Lazare Carnot . He was executed on August 16, 1894. (May his memory be a blessing.)

In Monza, Italy on July 29, 1900 the Italian-American anarchist Gaetano Bresci stabbed King Umberto I to death. The death penalty having been abolished, he was sentenced to life imprisonment. He was found dead in his cell a year letter, a supposed suicide. (May his memory be a blessing.)

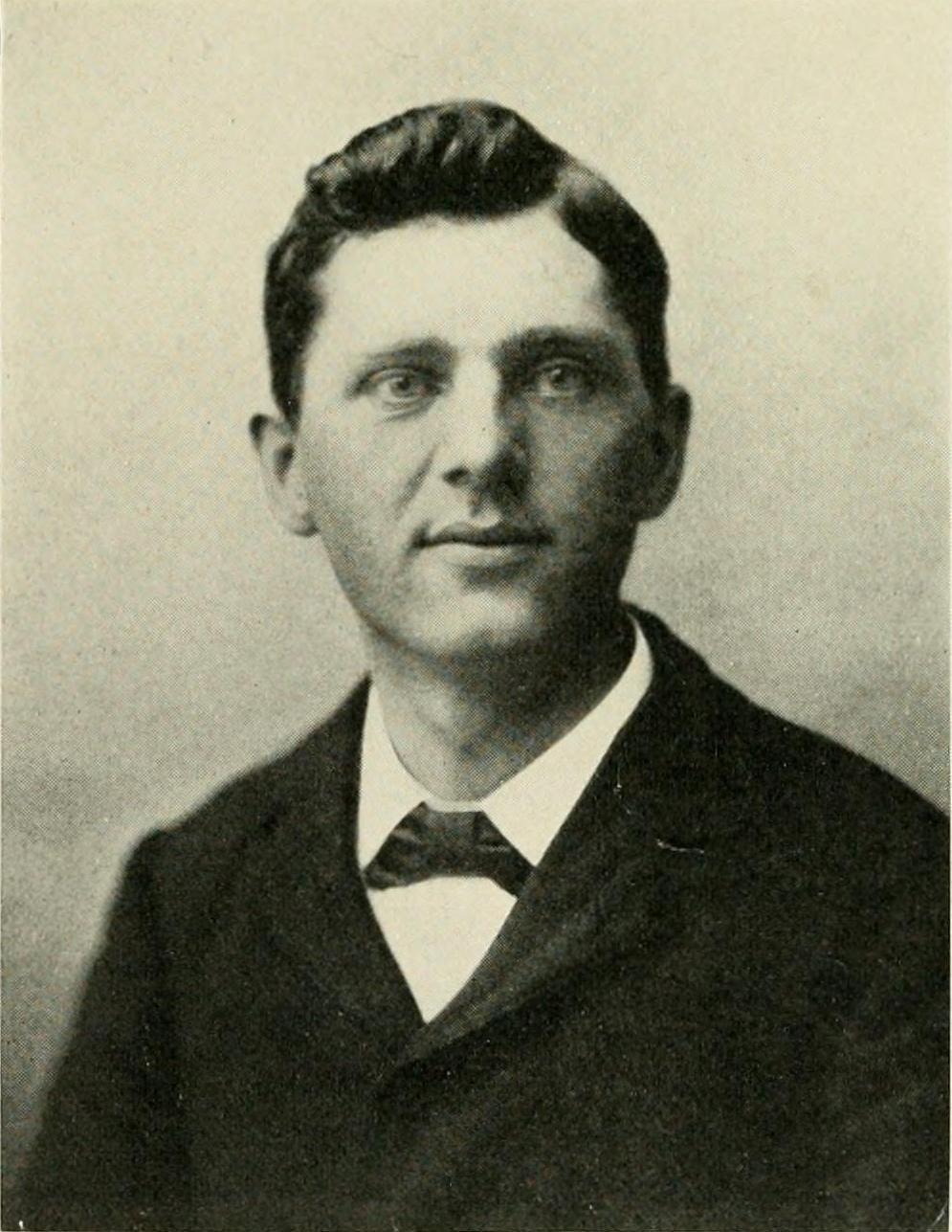

These events, the high points of the anarchist tactic of propaganda by the deed, all occurred during the political education of the American anarchist Leon Czolgosz who, in Buffalo on Sept 6, 1901, assassinated President William McKinley.

At the time of his act some considered him insane since, as a contemporary medical authority put it, “to assume that he was sane is to assume that he did a sane act.” This explanation exculpates Czolgosz by removing any meaning from his gesture, but it also exculpates American capitalism. But Czolgosz’s act was not the fruit of a sudden impulse or of dementia. It was the conscious response of a worker and radical to the situation in turn of the century America.

Czolgosz’s life was in many ways typical: the child of immigrants, he was born in 1873 in Alpena, Michigan, not far from Detroit. In search of work, the family moved, settling near Pittsburgh, where Czolgosz began his education in working class life at age sixteen at a glass factory. He later moved to Cleveland, where he worked in a wire factory and, in 1893, participated in a strike that led to his being blacklisted and only being able to return to the workforce under an assumed name.

“I’ve Got Money Singing in My Brain!”: DECOY (1946)

It’s just one cruel joke after another. An executed man is brought back to life, only to be shot dead minutes later. A noble doctor who has devoted his life to serving the poor is seduced and duped by the world’s most avaricious woman, who shrewdly points out, “You like to smell the perfume I use. This perfume costs $75 a bottle.” Her partner in crime enjoys gloating over her victims, only to become one of them when she stomps on the gas pedal while he changes a flat tire. As she lies dying, the woman asks the cop who has hounded but reluctantly admires her to “come down to my level, just once”; then as he finally succumbs and leans in for a kiss, she laughs in his face. For a finale, the box of loot she died for turns out to be filled with worthless scrap-paper. It’s the decoy; so is she; and so is money, the love-substitute, sex-substitute, life-substitute that makes this grubby world go round.

Cliff Edwards: He Did It With His Little Ukulele

Cliff Edwards is better known as Ukulele Ike, and best known as Jiminy Cricket. But cast an eye down his movie credits, from 1929 through 1965, and the names of his characters form a jazzy found poem of monikers. He was Froggy, Foggy, Owly, Pooch, Snipe, Bumpy, Screwy, Louie, Stew, Dude, Rooney, Snoopy, Pinky, Sleepy, Shorty, Runty, Speed, Tip, Tips, Hogie, Handy, Happy, Harmony, Nescopeck, Minstrel Joe, Banjo Page, Bones Malloy, and—my personal favorite—Squid Watkins. This slang menagerie says a lot about the off-beat appeal of one of the 20th century’s most unique and endearingly oddball talents.

Clifton A. Edwards was born in 1895 in Hannibal, Missouri, hometown of that other great American master of the nom de plume, Mark Twain. He grew up poor, selling newspapers on the street. A natural performer, he ran away and by 16 was singing in saloons and carnivals in St. Louis, where he picked up his nom de uke courtesy of a waiter who couldn’t remember his real name and dubbed him Ukulele Ike. He had adopted the tiny Hawaiian guitar and the kazoo so that he could accompany himself as an itinerant entertainer. He rose through vaudeville, teaming up with the comedian and eccentric dancer Joe Frisco, then achieved his first great success on Broadway in the 1924 Gershwin show Lady Be Good, starring Fred and Adele Astaire, in which Edwards introduced the hit “Fascinatin’ Rhythm.”

His trademark instrument, with its comical size and association with 1920s hot-cha frivolity, suited Edwards’ vaudevillian persona, but may have tended to obscure his serious gifts as a musician. He does get credit for being among the very first white artists who can truly be called a jazz singer; he knew how to swing a song and how to elaborate on it by scatting and imitating instruments—in his case, with wild kazoo-like choruses, bluesy muted-trumpet growls, and uninhibited yowls suggestive of a cat on a back fence. But Edwards could also croon a straightforward love song in a high yet natural tenor—pure, warm and unadorned—that is far from the ludicrously effeminate falsetto affected by many twenties crooners, or the limp, wan stylings of Rudy Vallee. He could even redeem sentimental pablum with his simple and tender delivery. Though he lacked suave looks or a husky, sexy voice like Bing Crosby’s, he brought vulnerability and honesty to love songs without ever slipping into the maudlin.

Fortuitously Charitable Byzantine Contaminations

1

if you want to get rich it’s no problem in this day and age to find yourself as rich as you want by simply moving with all your strength and spirit from poverty to wealth and there are all kinds of ways to accomplish that feat such as gathering up the loose money you have laying around and investing it in a company that will eventually grow astronomically at some point in the future or you could buy a fishing rod with it and spend all your mornings in the bosom of nature reeling them in and in the afternoons peddling them close to where people live who have no fish for example farthest from the coast or you could devote a good amount of time trying to come up with a plan that tricks some fool into giving you his money soon parted upfront for an imaginary much-wanted thing so much better than what he already has or maybe kidnap the bank manager or someone with their paws in a bucket of cash and threaten to get rid of his kids and wife if he doesn’t load up a sack and bring it to the parking lot without alerting anyone or you could go in hard with machine guns blazing and in a few hectic seconds be ripping down the road with a mother-load on the seat beside you and a future looking much brighter than it ever did or could by just working your dumb ass off only to keep seeing your bills go up as the system nickel and dimes you into despair and apathy where you just settle into waiting out the zoo-life until the end like a game lost early but still a whole lot of time on the clock

When the Stars Began to Speak

“Did you ever hear a dream talking?” (line from an old song)

What was lost and what gained, crossing the great techno-divide between movie pantomime sometimes as stylized as ballet, and an initially stagey yackety yak? Film had been visual, fluid and rhythmic, with live music helping to transport audiences into The Bigger Than Life Beyond. The big deadweight soundproof box, containing both camera and asphyxiating operator, then fell on this dancing medium… flooring it. What would survive? What replace? And what become of the beloved genii of body language, the clowns, drooping tragediennes, aging sweethearts? And – even more crucially – of highly developed camerawork and editing. The Depression was on, Prohibition a corruptive disaster, and the movie temples needed to quickly distract their idolator congregations from seeking economic/political solutions to their predicaments. Raunchy was still possible; the “Code” had yet to institute twin beds throughout moviedom; Mae West became box office queen, and everyone bandied her lines. Distinctive talkers were in: Cagney, Robinson, Boop, Popeye. Tapdancers were in! The Marx Brothers stormed in with their deliciously clutzy first feature, The Cocoanuts. Black shoestringer Oscar Micheaux ingeniously stuck sound onto his unintentionally surreal Ten Minutes To Live. Talk, yes, but how? (I address those in particular who are interested in WORDS.) The movies weren’t life, or stage-theater, or novel. (The Frankenstein monster, opening his mouth to speak, says, “Smoke… good. Friend… good.”) The Muse of Cinema, caught between styles, exerts a special charm, with so much actuality showing through. Less avant-garde than off-guard, the movies were never more “dated” (transparent, that is, to the time and circumstance of their making), more vulnerable or touching.

by Ken Jacobs

The Language of Revolution

Language is a revolutionary weapon, and the choice of vocabulary used, the choice of either high speech or slang, speaks volumes about who wields the weapon and who they are wielding it against. The Great French Revolution has much to teach us in this regard, and it is within the left of the Revolution, from the Jacobins to the Sans Culottes, that we see how expressive linguistic choice is of political tendencies: the farther left the group, the farther from standard speech. The more slang, the more revolutionary the figure.

There is no clearer way to see this than by comparing the Jacobin leader Maximilien Robespierre and the most outspoken of the ultra-revolutionary Sans Culottes, Jacques Hébert, and his notorious newspaper, “Père Duchesne.” In communist historiography Robespierre has been the voice of the left, a precursor of Lenin: the communist historian Albert Mathiez even produced a pamphlet in 1920 proving that the Incorruptible was a Bolshevik avant la lettre. But Robespierre was a provincial lawyer who had gone up to Paris, defender of the most progressive wing of the nascent bourgeoisie, and enemy of the revolutionary workers of the faubourgs, of whom Hébert was the main spokesman. The audiences of the two men were different, their means and goals were different, and so they spoke differently.

Robespierre, in a speech given on June 22, 1791 at the Jacobin Club on the flight of the king, in the style of the time among the revolutionary political class, referred to Marc Antony’s being “camped around Lepidus,” of there being “nothing left for Brutus and Cassius but to kill themselves.” Of Antony “command[ing] the legions that are going to avenge Caesar! And it’s Octavian who commands the legions of the republic.”

Similarly, in a speech on the death penalty he spoke of how in Athens, “when news was brought that citizens had been condemned to death, people ran to the temples, where the gods were called upon to turn Athenians away from such cruel and dire thoughts.” Later, he refers to Scylla and Octavian and the Roman example. (The speech, ironically for a man known for having sent thousands to the guillotines, was a plea against the death penalty.)

However common these references were at the time, these appeals to the history and righteousness of Antiquity could not have meant much to the working class crowds that pushed the revolution forward on the streets and won the great victories on the battlefield.

They would have found a more familiar voice, a more familiar frame of reference in the pages of “Père Duchesne,” the profane journal edited by the Enragé Jacques Hébert. There are no arcane references to Roman heroes or appeals to abstract principle in Hébert’s writings. Legalistic arguments had no place in his discourse, and pity for the fate of those who had oppressed the people was foreign to him. On the imprisoned Louis XVI: “The crapulous Louis gave himself over to excesses, and with his drunken hiccups vomited his bile and exhaled the boldest insults against the people, his sovereign.” And the issue of sovereignty is not the subject of learned treatises or references to Solon: “Oh fuck; never forget that sovereignty resides in the nations, which makes the laws which the monarch rules by.“

And this “fuck” was his trademark. Hébert’s writing was nothing but a transcription of the speech of the man of the people, which his invented mouthpiece Père Duchesne, was set up to be. So he was in a state of rage over “the fucking slanderers of the ladies of les Halles and the flower sellers” who had dared speak their minds about the king, those who complained of these working women being “fucking asses.” For “isn’t anyone of whatever position a citizen? And doesn’t he or she have the right to speak to his king?” And he had no use for the merchants who were charging the people exorbitant prices for subsistence goods: “Fuck! The merchants have no fatherland, and they only supported the Revolution as long as it was useful to them.” And when a maximum price for goods was imposed and famine struck when merchants held back goods from circulation, he wrote: “Fuck! I see a league formed of those who sell against those who buy!”

It was this directness and extremism of expression, this use of slang and popular speech that brought Hébert to the forefront, helping him to lead the popular masses of Paris. But at the same time it made him vulnerable to the attacks of his enemies, Robespierre and the Jacobins. For his lack of measure in language was an expression of his lack of measure in politics. If Robespierre founded a religion worshiping Reason, Hébert pushed for a radical dechristianization. His choice of how to write showed who and what he chose to represent.

John the Revelator

Anyone interested in literature has his/her own nominee for greatest American stylist. I think, overall, I’d go with Herman Melville (more on that another time). In the 20th century, you’ll find votes for H.L. Mencken, a man of cutting wit, rambunctious verbal hijinks and unlimited opinion.

Well, here’s someone who can match Mencken. John Greenway was an anthropologist on the faculty of the University of Colorado. He was also one mean son of a bitch who disliked most other anthropologists and all levels of authority, respected yet castigated the peoples he studied and breathed fire across the broad swath of modern civilization.

He hated liberals, but like many another sum’bitch rightist (Mencken, Westbrook Pegler), he had intense personal loyalties for those few, who, in his lights, devoted their time and existence to the honorable work of the world. (Rightist sum’bitches are loyal to individuals; leftist sum’bitches are loyal to causes.)

I first ran across Greenway from an album of folk songs he put together in the late ‘50s or early ‘60s. He was a terrible singer—high-pitched, wavery, uninflected, almost unlistenable. I’m sure he didn’t care; only the music he was presenting mattered.

To be fair, I’ve read only one of his books, and that only twice. On the other hand, there are few books I’ve read more than once, even those I dote on in theory. I generally hate re-reading something until I’ve forgotten its incidents and it’s become fresh again.