Robert Mitchum: A Constant Motion of Escape

“You just sit there and stay inside yourself,” Kirk Douglas says to Robert Mitchum in Out of the Past. “You sure are a secret man,” his girlfriend observes in the same movie. Then a cab driver tells him that he looks like he’s in trouble, “because you don’t act like it.”

They could be talking about the actor as much as the character he’s playing, and this keeps on happening in Mitchum’s movies. People remark on his inscrutability and lack of ties, calling him “a strange stranger” (The Yakuza) and “a man who’s made it his business all of his life to keep under cover” (His Kind of Woman). Sometimes Mitchum himself seems to speak through his characters, as when he boasts in Thunder Road: “I don’t make no deals with nobody…I don’t buddy up with one living soul.”

Being alone and adrift, always on the move and on the outside, demands monumental self-assurance. Onscreen, Mitchum looks oddly comfortable in his doom-haunted alienation, relaxing into his peculiar blend of lucklessness and invincibility. A guarded enigma, he’s also a rock-solid, radically independent presence. Keely Smith speaks for many when she tells him in Thunder Road, “I just want you altogether, ’cause you’re the only natural man I ever knew.”

***

Robert Mitchum was, both onscreen and off, a mystery. Off-screen, the mystery was whether he really cared as little as he took care to make it seem. Howard Hawks, after working with him on El Dorado, called Mitchum the biggest fraud he’d ever met, confronting him with the fact that, while pretending not to give a damn, he was actually the hardest working actor around. Mitchum’s reply: “Don’t tell anybody.”

We Go Through Life Thinking We’re Bogart

Making a list of the great films in which he appeared would be pointless. It would go on too long and you know them all anyway.

He was a small, mousy little fellow with pinched features beneath a high forehead, wide, watery eyes, a mouth that could not smile and a voice pitched slightly too high. He was factory-made to play nebbishes, henpecked husbands, elevator operators, front desk clerks, twitchy sidekicks, newsboys, the unjustly accused, informers, and the doomed would-be tough. Even as he aged, he was like a puny kid who always wanted to be bigger so he could show all those other kids. He was the Eternal Small-Timer. In short, he was Everyman, and a character actor’s character actor.

Lon Chaney: Losing Yourself

When Charles Laughton ended his stupendous run of character parts in films of the 1930s by playing Quasimodo in The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1939), he found a painfully innocent agony within that role, especially when Quasimodo is whipped in a public square. Lon Chaney also played Quasimodo in a silent film version of The Hunchback of Notre Dame from 1923, and he doesn’t seem to believe in the innocence that Laughton stands up for. Half blind and deaf and burdened with a large hump on his back, Chaney’s Quasimodo is physically agile in a way that Laughton could never be, and he sneers at the townspeople who scorn him, sticking out his tongue at them. The agony of his Quasimodo is served straight with no chaser, and no larger point to be made. If Laughton gets further in the role and moves it to an abstract plane, Chaney is far more realistic. He does not sentimentalize, and his presence is harsh, unsparing.

They called Chaney The Man of a Thousand Faces, but so many of those faces were twisted, sneering, deformed, pulled back, pulled down, contorted. He was obsessed with amputation, impairment, ugliness. And when his face was unadorned by his beloved make-up, it knew that a particularly nasty trick of fate was coming. In Lon Chaney movies, nasty tricks of fate come with such regularity that you begin to doubt if anything good has ever happened or ever will happen to anyone. Could he have been romantic, charming, appealing? Or did he not have any faces for that, or any belief in such things? He was a one-man rebuke to the Jazz Age, a tough medicine to counteract all that whoopee and bootleg gin.

Chaney was born Leonidas Frank Chaney in Colorado in 1883. Both of his parents were deaf. “I could talk on my fingers, but as I grew older, I found it unnecessary,” Chaney said. “We conversed with our faces, with our eyes.” And so Chaney became adept at the art of pantomime out of necessity. When he was twenty, Chaney started working in theater and vaudeville acts, and he married a singer named Cleva Creighton in 1906. After the birth of their son Creighton Chaney, who later took on the professional name Lon Chaney, Jr., Chaney and his wife were separated for long periods and their relationship began to deteriorate. In April of 1913, Creighton went to the Majestic Theater in Los Angeles, where Chaney was managing a show, and attempted suicide by swallowing mercuric chloride. Though she lived, her singing voice was ruined. This supposedly caused a scandal in theater circles, and Chaney was forced to look for work in motion pictures to make his living.

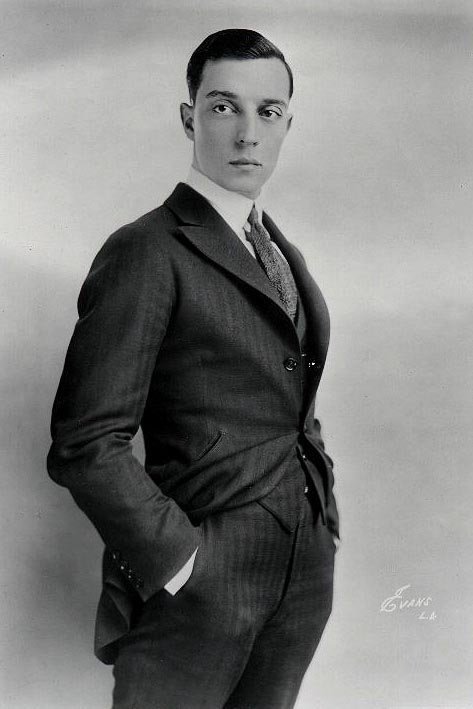

The Stoneface Speaks

As the story goes, W. C. Fields once stood up during a screening of a Charlie Chaplin film and angrily announced to the screen and the rest of the audience, “He’s not an actor—he’s a goddamn ballet dancer!”

There’s something to that, of course. Through all his antics and pratfalls, Chaplin’s movements were always delicate and graceful. He was always in control, and the well-rehearsed and careful choreography that was behind those pratfalls was right up there on the screen, clear as day. By contrast, the magic of Buster Keaton was that he could take sophisticated stunts that were just as well-rehearsed and carefully choreographed and make them seem clumsy, awkward, and accidental.

And while Chaplin’s characters, though often downtrodden, were still clever enough to use their wits to get out of most any scrape and win the girl in the end, Keaton’s were just, well, hapless. They stumbled out of trouble the same way they stumbled into it—by happenstance and sheer dumb luck. And if he did happen to win the girl in the end it was more likely an accident than the result of any endearing charms he might possess.

As with so many silent stars, the introduction of talkies was a very tumultuous period for Keaton, but not for the usual reasons.

His laconic Kansan twang fit his face and his characters perfectly, with its natural blend of naive, straightforward sincerity and befuddlement. It served the Stoneface well, and added yet another layer to his performances. Or would have, had the studios chosen to capitalize on it.

As the talkie era got underway, Keaton signed a contract with MGM. It kept him working, but in much smaller roles in smaller and weaker films, and without the level of creative control he once enjoyed. A number of personal problems began cropping up as well, and that didn’t help matters.

Then in 1934, he signed with Earl W. Hammond’s Educational Pictures. It seems an odd and unlikely move at first, an iconic comic actor of Keaton’s stature leaving MGM for an industrial house, until you learn that Educational’s real bread and butter at the time was their comic short subjects. The move also once again gave Keaton the creative control he’d been missing, and allowed him to return to the smaller, tighter format where he’d started, and take it in some new directions.

Over the next three years, mostly working with director Charles Lamont (the prolific filmmaker best known for his Abbot & Costello films from a decade later), Keaton would slam out sixteen two-reelers, one after another. While his trademark form of hapless slapstick remained front and center, the addition of sound gave him a new toy. Along with the expected crashis and smashing glass, Keaton also began to play around with the musical and comic potential of natural sounds.

The first half of 1935’s One-Run Elmer, for instance—in which Keaton runs a dilapidated gas station in the middle of nowhere—is played in near silence, save for the squeak of a rocking chair, a cowbell, some dropped change, and the clinking of a gas pump. Somehow, though, through a combination of timing and gesture, he’s able to turn it all into a brilliant and hilarious (if discordant) symphony. In the years that followed, it’s a routine that would be adapted by everyone from Ernie Kovacs to Ennio Morricone.

Then there’s Elmer. With the exception of two of the sixteen films (1934’s The Gold Ghost and 1935’s Palooka from Paducah), Keaton’s on-screen persona throughout the series was Elmer, the wide-eyed, naive, always helpful, always hopeful, and perhaps too-polite Midwestern lad with a bad habit of innocently fumbling his way into trouble and falling in love with every pretty girl he sees. Elmer actually first appeared in 1932’s The Passionate Plumber, but in these shorts Keaton had the space and the freedom to develop him more fully.

Here once again sound becomes an invaluable addition. Not only is Keaton’s voice perfect for the character, but he also reveals himself to have perfect, low-key verbal timing.

In 1935’s Hazed Romance, he arrives at a farmhouse in answer to a newspaper ad. The large and severe woman who runs the farm tells him, “I’d offer you something to eat, but we’ve already had dinner.”

“Oh.”

“But you can wash most of the dishes if you like.”

He waits just the briefest of beats before saying, “Thanks!”

It’s a quick exchange that could easily slip past some viewers and certainly wouldn’t translate well as an intertitle, and the Elmer shorts are full of subtle bits like that. Quiet, off the cuff remarks that likely never would have cut it in the silents. (When Elmer stops at a drive-in restaurant wearing a boy scout uniform, a waitress asks him in passing, “So what are you, a big game hunter or just giving your knees an airing?”)

W.C. Fields, Post-Modernist

By 1941, following a string of hits that would be considered iconic in the years to come (My Little Chickadee, The Bank Dick), W.C. Fields’ drinking began to take a serious toll both on his health and his ability to perform. It was becoming clear he might not be able to carry a film for much longer. He did, however, have one film left in him, and it would turn out to be not only his strangest picture, but also one that was—if accidentally—years ahead of its time.

The Jowls of the Earth

Many actors – one thinks of the great Matthau at once – could earn the descriptor “hangdog,” but maybe only Walter Connolly owns it. He looks like somebody literally hanged a dog. They might have buried the word with him, since nobody else can lay claim to it so well anyway.

Connolly’s face exudes suffering. He may, at some point, have appeared on advertisements for liver pills. His very appearance is enough to trigger sympathetic gastric pangs in the viewer. Not all fat men are merry.

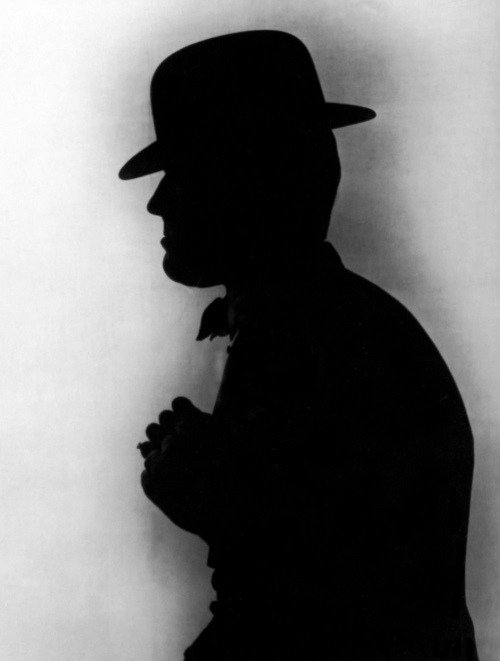

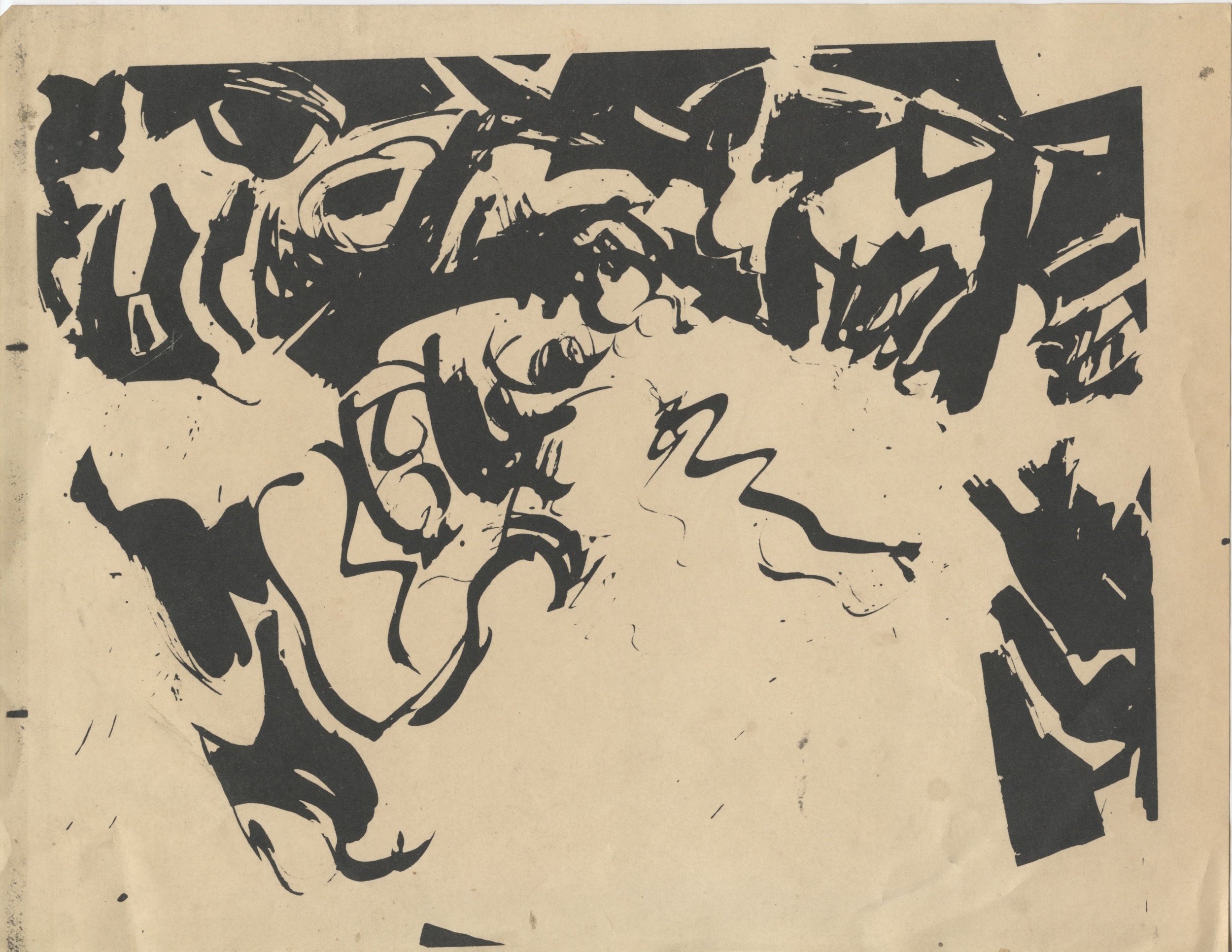

Ken Jacobs: “Movie That Invites Pausing”

A drawing to accompany MOVIE THAT INVITES PAUSING. Just watched it through again, giving it more time than before. Astonishing; it’s off on it’s own, the maker is as mystified as anyone. Hope I can make another.

Reader/adventurer: I’m looking to see this projected big, but I cannot think of it as one of my films: it is unquestionably a video and that only. There are many black frames between images and -when projected- the projectionist is asked to stop often and on an image. Fat chance. You will meet up with the problem seeing it at home. The space bar together with the single frame advance key (bottom right) should do it.

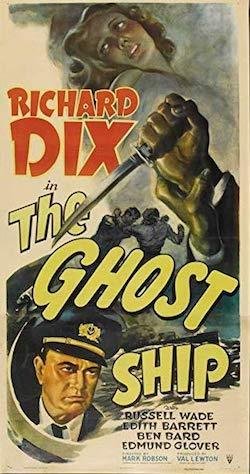

High Seas Noir: THE GHOST SHIP

RKO came late to the horror party, only seeing the economic virtues of low-budget spook shows after the box office disaster of Citizen Kane. Like the other studios who’d been following Universal’s lead since the early ‘30s, when RKO decided to start up a horror division in 1942, they wanted to do something different, something that would make RKO’s monster pictures stand apart from everyone else’s. So they brought in former pulp novelist Val Lewton to take care of things. Lewton, by all accounts, was a very hands-on producer who was deeply involved in every aspect of his films, from writing to lighting to directing . As a result, all nine films he produced bore his personal style, and they were all undeniably unique. Only problem was they weren’t exactly the franchise-ready monster-fests the executives were expecting.

Who Has the Last Laugh

I can’t remember just when I first read “Comedian’s Children.” Like most of Theodore Sturgeon’s short stories, probably shortly after it came out in paperback – in this case, around 1957.

“There’s Nothing That Makes People Laugh So Hard”

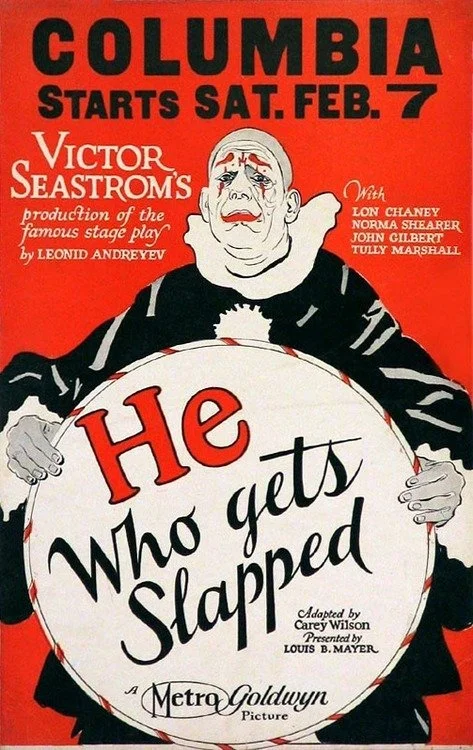

To call 1924’s He Who Gets Slapped perhaps the creepiest and most disturbing film of Lon Chaney’s career is saying quite a bit, especially as it was made smack in the middle of his 10-film collaboration with Tod Browning—a collaboration that gave us films like West of Zanzibar and The Unknown—but there’s something about the vengeful clown picture that wriggles under the skin and settles in the subconscious. For those of us who came to the film with a deep and profound fear of clowns already in place, it’s like a nightmare realized.

Written originally as a Russian novel by Leonid Andreyev, Tot, kto poluchaet poshchechiny (as it was known) was adapted for the stage by the author and, in 1916 received its first film treatment under the direction of Aleksandr Ivanov-Gai . This should come as little surprise, as although the story is set in Paris, it remains inextricably Russian in character.

In 1922 the novel was translated into English as He Who Gets Slapped and again adapted for the New York stage by Gregory Zillboorg. The play was a minor hit, but still enough of a hit that the rights were picked up by the newly-formed Metro Goldwyn Mayer studios and handed to Victor Sjöström, the father of Swedish cinema, to direct. That makes a lot of sense, too, once you become familiar with the plot. And given that the star would be spending two-thirds of the film in clown makeup, casting Chaney seems to have been a forgone conclusion.

He Who Gets Slapped was the first film to be shot in MGM’s new studios, but the release was delayed a few months until Christmas in order to draw bigger crowds for what was obviously a, y’know, Christmasy-type film for the whole family.

Letter from Arthur Rimbaud to M. Lucien Hubert, Minister of Justice

Dear Guardian of the Seals;

Since you have just conjointly accepted the vice presidency of the Council of Ministers and that of the society of my Friends it is important you know that as a former Communard, petroleur, etc. I consider myself in solidarity with the imprisoned members of the French Communist Party (French Section of the Third International). I also intend to attend in person a meeting of those Friends of whom you are the vice president in order to, among other things, stir up the dirty question of police conspiracies and brutality. In this regard, as relates to my Friendship, who is this Monsieur Renier, your hierarchical superior? Doubtless a caropolmerdis [1] big shot, like you. It’s unheard of how well regarded I am beginning to be by the grocers there.

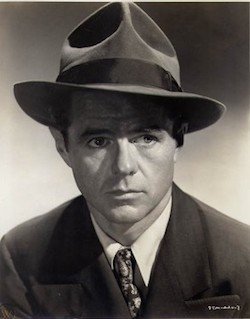

Monroe Owsley: No Good

An early 1930s fan magazine letter about Monroe Owsley reads like this: “He’s a slimy toad, a no-good rat up to trouble—and you feel he’s like that off-camera too!” The jury is likely permanently out on any off-camera sliminess, but Owsley was the center of many sordid rumors before his premature death in 1937 at age 36, when he supposedly had a heart attack after an automobile accident.

It was said around Hollywood that he was beset by drink, drugs, and gambling and that he had gay leanings and acted on them, though MGM starlet Anita Page said near the end of her life that he was in love with her in the mid-1930s. He was intensely in love with a lot of people, it seems, and furtive, and maybe a little wicked.