Boris Karloff Almost Saves the World

Throughout his long and storied career, Boris Karloff played any number of mad scientists whose diabolical experiments (and the inevitable string of murders they required) were aimed at gaining some form of wicked personal glory. He wanted his own unstoppable zombie army, say, or the means to destroy those critics who had laughed at him and called his ideas “insane,” or he just wanted to rule the world.

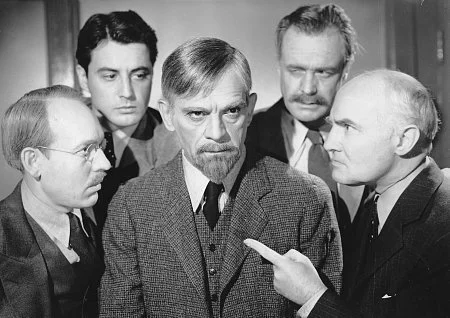

But around 1940 he starred in a cluster of films in which his mad scientist character wasn’t mad at all, but was only trying to do what he could to benefit all mankind. Unfortunately these sane and noble doctors more often than not found they were working in a mad world, and were destroyed for their efforts. They make for rare instances in which the King of Horror plays a sympathetic role and it is the world around him (and all those stupid meddling fools he’s trying to help) that are the real kings of horror.

In the first of these films, 1939’s The Man They Couldn’t Hang, Karloff plays a medical researcher who devises a new form of anesthesia. By covering the body in ice cubes, see, and using a mechanical heart to pump cold liquid through the veins, it’s possible to reduce the body’s functions to nil—essentially killing the patient—while still being able to revive the patient at some later point without any tissue damage. This would mean a great leap forward for surgery. Operating on a living body, he explains, is a bit like trying to fix a car engine while it’s still running. But if you shut the engine off, you can take it apart, fix what needs fixing, put it back together and have it running as good as new. Same with working on an ostensibly dead patient—a surgeon can take his time, do a careful job, and not have to worry about racing the clock.

Unfortunately his first human trial of the technique (with an eager and willing assistant as the experimental subject) is interrupted when his meddling nurse (also the subject’s fiancee) runs to the cops to report that the doctor is murdering someone.

Well, the experiment is ruined and Karloff is put on trial, convicted by a stupid lawyer and stupider judge and jury, and sentenced to hang.

Following his execution Karloff is revived using his new technique. Instead of using that evidence to prove the validity of his theory to the world (or even using this second chance to further his research), he goes into hiding and turns his old house into a giant mousetrap which he then uses to exact revenge against all those who convicted him. Which I guess is what you get.

Following the success of The Man They Couldn’t Hang, Karloff returned in 1940 in a similar role in a similar film—even playing a doctor with a similar theory. In The Man With Nine Lives, however, instead of using low temperatures as a kind of anesthetic, he argues that if you freeze cancer patients solid, the process itself will shrink and effectively kill tumors while leaving the surrounding tissue unharmed allowing the doctor to revive a perfectly healthy patient (using blankets and coffee) at some future date weeks, even years following the initial freezing. Once more his theories are ridiculed by the short-sighted medical community, forcing him to carry out his experiments in secret on a small island in upstate New York.

Well, things happen and Karloff is frozen in an ice cave in his basement along with a lawyer, doctor, and constable from the mainland, as well as the angry and suspicious son of his latest patient. Ten years later they are all revived by a curious doctor from New York. Even after learning that his theories have come to be widely accepted in the ten years he’s been on ice, Karloff’s first and only goal upon being reawakened is to kill those people who were trying to persecute him.

That same year in Before I Hang, Karloff is again convicted for losing a patient, upon whom he was trying an experimental treatment. This time while in prison he’s allowed to continue his experiments. Testing a youth-restoring serum (love that term, “serum”) on himself he finally discovers the formula he’d been looking for. The clear and obvious benefits it offered all of mankind lead the state to parole him. Unfortunately the serum was distilled with the blood of a mad killer, which in the end leaves Karloff a little kookoo bananas in fits and starts, and so the killing begins again. Nevertheless it was a splendid idea so long as the serum is made with, you know, non-killer blood.

All three films, though penned by three different screenwriters, were directed by the prolific B-film maestro Nick Grind. Grind was never known for his horror films, which is why it’s difficult to call these horror pictures. More accurately, they’re mystery thrillers with a pseudo-scientific backdrop. The evil that Karloff undertakes is always made clear and understandable and sympathetic. It’s very human. He was trying to do something good and noble, until he was stopped by ignorant morons who refused to see the possibilities of a world beyond what was at hand. And let’s face it—they deserve to be killed for what they destroyed.

Karloff didn’t stop with Grind, however. Once more in 1940 he played a doctor who was trying to do the right thing and was sent to the chair for his efforts.

In Arthur Lubin’s Black Friday, Karloff, a brain surgeon, tries to save a close friend’s life by using an illegal experimental procedure to transplant a new brain into his body. Unfortunately he chooses the handy brain of a gangster. When he learns the gangster had a half-million in stolen loot stashed somewhere before he died, Karloff decides to probe his friend’s new brain to see if it remembers where the loot is hidden. After all, that money could be used to build a new research facility to help other people with brain problems. Unfortunately the gangster brain (as is so often the case with brains) has other ideas, mostly involving the murder of all of his old gang members and keeping the loot for himself. Throughout, it’s clear Karloff’s intentions are quite noble, but he finds himself in over his head dealing with a Jekyll/Hyde case and a gangland war. In the end it’s Karloff who gets the chair for putting a stop to all the madness.

These were all good, tight, clever, entertaining films (Nine Lives can even boast some very striking and beautiful cinematography) and despite the fact that Karloff was playing against type as a good guy trapped by ignorant circumstances, they were popular with audiences as well. One has to think that Karloff himself must have found the roles a bit of a relief. Although he never denied that he owed his career to playing Frankenstein’s monster, as a cultured and sophisticated man himself, he must have found something in these characters to latch onto. Like the doctors he played, he was a very intelligent and skilled man working in an often short-sighted industry controlled by dullards.

Over the next twenty years he returned to the more traditional horror films (some quite good, some less so) and he always gave an interesting and nuanced performance. But then in 1958 he once again played a doctor on the verge of easing some of mankind’s pain only to be doomed for his efforts in the deceptively titled Corridors of Blood.

Although marketed as a horror film, the great Robert Day’s stark picture is more a grim historical drama combining several actual events and characters into a story about the horrific state of public medicine in 18th century England, where the surgeon’s mantra is “pain and the knife are one.” Karloff stars as Dr. Thomas Bolton, a surgeon who refuses to accept that mantra and devotes himself to finding an effective anesthetic, much as he was doing in those earlier films. Here, however, the circumstances are much more pressing and the results are not nearly so tidy. Enter a pair of Burke and Hare doppelgangers and well, things just get complicated.

After experimenting on himself at home, Dr. Bolton discovers the benefits of nitrous oxide gas in a frenzy of hysterical laughter and smashed glassware. Deciding to push his experiments further, the well-intentioned doctor soon finds himself addicted, and his addiction leads to nothing but trouble.

While neither the first film about drug addiction nor the first historically-based drama about the search for painless surgery, Corridors of Blood remains among the most striking and effective films about the perils of trying to help mankind. Karloff gives a believable and moving performance, and though Bolton dies having yet to find the solution he was searching for, he at least dies knowing he’s laid the groundwork and that the solution will be found. Better still, he didn’t even have to murder all those short-sighted hospital administrators first.

After Corridors of Blood Karloff, having tried one last time to save the world, returned once again to more traditional horror films, some quite good, some less so.

by Jim Knipfel