Scum

Valerie Solanas was thirty when she arrived in Greenwich Village in 1966. She’d been a teenage runaway and a drifter for some time, and she was quite damaged by the time she appeared. She grew up in New Jersey, where, according to a sister, their bartender father regularly molested her. Later, when her mother and a despised stepfather couldn’t handle her rebelliousness, they sent her to live with her grandfather who, she said, tried to beat it out of her. She ran away at fifteen and would profess a hatred of men for the rest of her life. Over the next few years she had a married sailor’s child who was taken away from her for adoption, but she still managed to graduate high school and do well at the University of Maryland, earning honors in psychology. After adding a year of grad school at the University of Minnesota she hit the road again, a hobohemian tomboy waif who panhandled and hooked her way to Berkeley.

She continued to turn tricks and bum change when she reached the Village, staying in the flophouse Hotel Marlton while trying to make it as a writer. In the February 9 1967 Voice she ran two small ads. One was for readings, at the Directors Theater School on East Fourteenth Street, of her play, which had one act but four titles:

Up Your Ass

or

From the Cradle to the Boat

or

The Big Suck

or

Up from the Slime

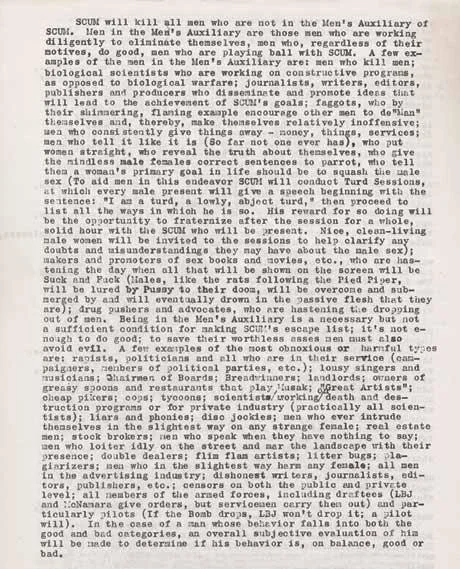

It also had three dedications: one to Me, one to Myself, and the third to I. The other ad was for her mimeographed pamphlet, SCUM Manifesto, which according to the ad was available for a dollar fifty at the Eighth Street Bookshop, the East Village shop Underground Uplift Unlimited and other venues. SCUM stood for the Society for Cutting Up Men. The pamphlet begins:

Life in this society being, at best, an utter bore, and no aspect of society being at all relevant to women, there remains to civic-minded, responsible, thrill-seeking females only to overthrow the government, eliminate the money system, institute complete automation, and destroy the male sex.

It goes on to describe all the ways males are deficient and depraved, as are all women who aren’t SCUM. It explains how SCUM will wipe most of them off the planet and create a utopia for the free, courageous, wise and groovy SCUM sisterhood. Up Your Ass delivers the same basic message in satirical dramatic form, as the Solanas-like character Bongi Perez – described forty years later in the Voice as “a wisecracking, trick-turning, thoroughly misanthropic dyke” – matches wits with variously loathsome men, a couple of them designated only as White Cat and Spade Cat, and street queens, and the straight women who distress her the most, who are willing to “eat shit” – literally – for their men. Both the manifesto and the play can be seen as early examples of the extremist feminist-separatist tracts that became more familiar in the 1970s. They’re crazed rants, but no crazier than when, a few years later, feminists picketing outside Barney Rosset’s Grove Press demanded fifty-one percent control of its operations. At least Solanas had a sense of humor.

With its eccentric ideas about the future, SCUM Manifesto can also be read as a distant cousin to William Burroughs’ mad sci-fi visions. That’s evidently how Maurice Girodias, publisher of Olympia Press, read it. Effectively Barney Rosset’s opposite number in France, Girodias published a mix of pornography and literature, the latter including works by Beckett and Henry Miller, Burroughs’ Naked Lunch and Nabokov’s Lolita. After several prosecutions on obscenity charges in France, he had moved himself and his press to the Chelsea Hotel in 1966 and was seeking edgy new writers to publish. They didn’t come with more edge than Solanas, who responded to an ad in the Voice and showed him the manifesto. He liked its bizarre sense of humor and gave her a five hundred dollar advance to write a novel on a similar theme. Solanas, with her long-engrained mistrust of all males, immediately decided he was out to cheat her and never delivered the novel.

By then she had focused her fiercely obsessive attentions on another male, Andy Warhol. She took a copy of Up Your Ass to the Factory. Warhol liked the title but apparently never read the play. Solanas began to hound him, in person and through innumerable phone calls, demanding the manuscript back, but it had been lost in the clutter at the Factory. (It wasn’t rediscovered for decades, and is now archived at the Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh.) Trying to placate her, he let her do a small scene in the movie he was then shooting, I, A Man. It didn’t help. She continued to stalk both Warhol and Girodias, demanding thousands of dollars she was convinced they owed her, working herself up with the idea that they were conspiring together to keep her down. She got a room at the Chelsea for a while, maybe to be close to Girodias, but was evicted for nonpayment of rent – which wasn’t easy to do at the notoriously easy-going Chelsea. She became a familiar crazy on the streets of the Village and East Village, hawking the manifesto, harassing male passers-by, trying to recruit women for SCUM, fitting right in with the sideshow milieu of speed freaks, flower children, acid casualties, religious nuts and street queens that was downtown Manhattan at the time. “For a while she was hanging out on St. Mark’s Place,” performer Agosto Machado recalls. “She just used to sit on a ledge, going…” He makes a nasty, angry face. “People would say, ‘Just leave her alone.’ She’d be picked up making threats and brought back in. I met her briefly, but I was so shy and she was a pretty strong person, even when she wasn’t talking.” He makes the angry face again. “You’d choose your words carefully around her, because what would come out of her could lacerate.”

She got herself booked onto Alan Burke’s late-night tv talk show. Burke was an abrasive conservative host who booked guests like an abortionist or a nun turned go-go dancer solely to harangue them. Solanas proved too much for him. She started cursing the minute she opened her mouth, and when she wouldn’t stop he stalked off the set in frustration. Sadly, the show never aired.

In 1968 she approached Paul Krassner, got a fifty dollar loan from him, and used it to buy a .32 caliber handgun. She already had a .22. On the morning of June 3 1968 she went to the Chelsea looking for Girodias. Instead of her normal tomboyish attire she was dressed for business, or dressed to kill, in a nice turtleneck and raincoat, with her hair done and wearing make-up, and carrying the pistols in a brown paper bag. After waiting around in the Chelsea lobby for a few hours she headed for the Factory, which Warhol had moved six months earlier from its original midtown space to 33 Union Square West, just across the park from his favorite hangout, Max’s Kansas City, the coolest club in the city at that point. Solanas sometimes went to Max’s stalking Andy, but then so did every other wannabe in the city. Where the original Factory, known as the Silver Factory, had been a cross between an art studio, a clubhouse and a drug den, the Union Square space signaled a new businesslike Warhol, organized like an office with a reception area and desks. The first time Solanas rode the elevator up to the sixth floor space that afternoon she encountered Warhol’s filmmaking partner Paul Morrissey, who, like most of Warhol’s crowd, had long ago decided she was a nut and a pest. He shooed her out. She rode the elevator up and down several more times that afternoon, until Morrissey threatened to beat her. Then Andy arrived. He was his usual passive, placating self, telling her how nice she looked. When Morrissey went to use the bathroom, Solanas pulled out the .32 and started shooting. Andy screamed and crawled under one of the desks as her first two shots missed. She calmly squatted, stuck the gun into his armpit and fired again. The bullet ripped through both lungs, his liver and spleen. She then put the gun to the head of Fred Hughes, Warhol’s manager, who had dropped to his knees. As he begged her not to shoot the elevator arrived. Solanas rode it down to the street.

Warhol was rushed to nearby Columbia Hospital, where the paparazzi were already magically waiting, and where he was initially pronounced dead before a surgical team went to work and saved him. Solanas wandered up to Times Square, where she handed her pistols to a rookie cop, telling him she’d shot Warhol because “he had too much control over my life.” By the time she was brought in for booking at the Thirteenth Precinct, a few blocks from where Warhol lay on an operating table, an enormous cloud of paparazzi had descended there, too. “I was right in what I did!” she shouted to them. She was remanded to the Women’s House of Detention and from there to a psych ward.

In Los Angeles, a little after midnight on June 6, Sirhan Sirhan upstaged Solanas by shooting and killing Robert F. Kennedy. In the shadow of that national tragedy, Warhol didn’t get much sympathy in the press; the general tenor was that his shooting was comeuppance for his amoral, decadent lifestyle. Some feminists embraced Solanas as a hero. She was in a psychiatric facility that August when Girodias published SCUM Manifesto, with a commentary by Krassner, “Wonder Waif Meets Super Neuter.” She pleaded guilty to reckless assault in 1969, and was locked up until 1971. She was arrested again that year for making new threats to Warhol and others. In and out of psych wards, she drifted to the Tenderloin in San Francisco, where she lived in relative obscurity in the 1980s, turning tricks again. She died in a welfare hotel there in 1988. In 2000, Up Your Ass had its world premiere in a theater just a few blocks away. It had its New York premiere at P.S. 122 in the East Village the following year.

by John Strausbaugh