Charlie Ruggles: Oh My My My

Howard Hawks’s Bringing Up Baby (1938) is a film filled with miraculously perfect comic line readings, and many of them are delivered by Charlie Ruggles as the oft-befuddled Major Horace Applegate, who enters the film over a low (not apple) gate, trying to correct Katharine Hepburn’s Susan Vance as to the time. “Pardon me, the time is 8:10,” he insists, and then he gets stuck astride the gate for a moment. He is wearing a goatee and a Tyrolean hat with a small feather and his light checkered coat clashes dramatically with his dark checkered vest. This is a farce, and so Ruggles’s character even dresses funny, and this is fun but unnecessary, for Ruggles’s stage-trained timing is more than enough to get laughs. When Susan asks who he is, The Major gets confused and dithers, “I’m 8:10,” but quickly corrects himself and announces his own name with a flourish.

The Major is the ultimate Charlie Ruggles performance because it gathers in all of his best bits, the way he lingers over his fussy catchphrase, “Oh my, my, my,” the way his voice breaks like an adolescent for comic effect, and the way he gets all caught up in a verbal ball of yarn and then has to somehow disentangle himself. At dinner, he tries to draw out Cary Grant’s distracted professor David, to no avail, and the funny thing about The Major is that he’s so pedantic yet so suggestible. After observing Susan and David rushing all over the place during dinner, he rises to face his hostess Mrs. Elizabeth Carlton-Random (May Robson) and asks, “Shall we run?” They gallop out the door, and once outside, Ruggles’s timing and emphasis is at its height as he does leopard mating cries and mistakes a real leopard cry for his hostess’s attempt at replicating one. “That’s fine, Elizabeth,” he says (he almost sings the line), before catching sight of the leopard and then hurrying Mrs. Random back into the house.

He was born in 1886, and yes, Ruggles was his real name, a name that promised comic delights to come (his brother Wesley went on to be a very fine comic film director). In his youth, his mother was shot and killed by a burglar. After that bereavement, Ruggles tried to please his father by studying to become a doctor, but he eventually went on the stage and had success in Battling Butler, which was later made into a silent film by Buster Keaton, and Queen High, which was made into a film in 1930 with Ruggles repeating his role as T. Boggs Johns opposite blustery Frank Morgan (Ruggles would often be paired in tandem with another flustered character actor, usually Roland Young or Edward Everett Horton). In Queen High, Ruggles is a serious, rather pained presence amid the musical comedy, and his big number, “I Love the Girls in My Own Peculiar Way,” details his love of murdering women! (he does sometimes visually resemble Chaplin’s Monsieur Verdoux).

This edge he displayed in Queen High was also present in the main body of his work for Ernst Lubitsch, for whom he made three films, plus a segment for If I Had a Million (1932), plus two films that were very much inspired by the Lubitsch touch, This Is the Night (1932) and Love Me Tonight (1932). In his first film for Lubitsch, The Smiling Lieutenant (1931), Ruggles gets his biggest laughs with nonsense sounds between words to signal his excitement and over-stimulation; vocally he sets himself on a kind of roller-coaster of energy and then stops to do a bewildered take. In his movies for Lubitsch and the two other sub-Lubitsch films, Ruggles wears mustaches of comically varying lengths; he suggests a dapper little eunuch who has heard about sex but cannot partake in it. Professing his desire to Jeanette MacDonald in One Hour With You (1932), Ruggles talks about “the animal” in him, and the joke is that there’s really no animal at all; it’s been civilized out of existence.

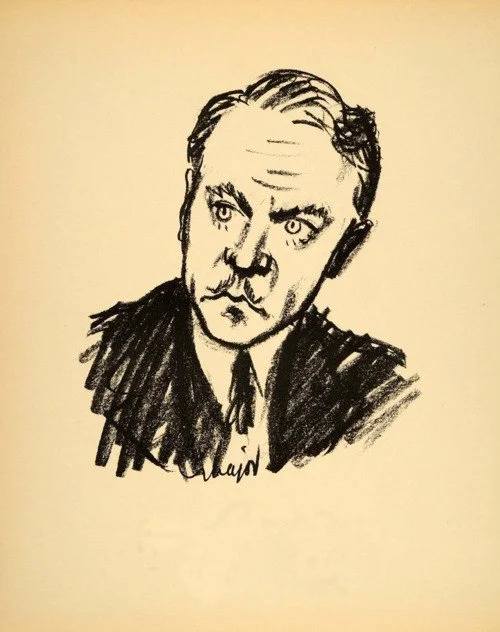

He plays another Major in his other truly great movie, Lubitsch’s Trouble in Paradise (1932), and Ruggles gets most of his laughs here by blinking. “I hate him because I love you,” he rattles out, staccato, speaking to Kay Francis of his rival Horton, and then he blinks several times in confusion. Ruggles in these Lubitsch movies is harsh-looking (except when he widens his little eyes), but meek-acting, a strange combination that serves the needs of these comedies of seduction and postponement.

In the mid-30’s, Ruggles played several hen-pecked husbands opposite the domineering Mary Boland, supremely in Leo McCarey’s The Ruggles of Red Gap (1935), and after the war he leant serious, dignified support to Bette Davis in A Stolen Life (1946), as a compassionate cousin who talks her through complicated love crises. After that, he played an understanding Father on one of the first television sitcoms, The Ruggles, and won a Tony for his comic relief role in The Pleasure of His Company, a part he recreated on film in 1961. By that point, he was a Grandfather to Hayley Mills in The Parent Trap (1961) and went on to bottom-of-the-barrel Disney fare like The Ugly Dachshund (1966). It was a long way from the 1930s Paramount salons of Lubitsch to the innocuous suburban settings of live action Disney films, but Ruggles remained ever-spruce, his timing impeccable under any circumstances up to his death in 1970.

by Dan Callahan