Places Are People: When the Setting is Ready for Its Close-Up

Cinema’s misspent childhood years in late-Victorian fairgrounds are followed by a grimy adolescence in Edwardian nickelodeon parlors. The medium, which finally comes of age amid gaudy palaces built in its honor, morphs many times. However, All Talking Pictures are the final death knell for the Victorian standard, belching from the screen a thousand inbred tongues that invade the ear willy-nilly. They remind us that Victoria Regina breathed her last in January of 1901, and with her passing Naturalism sheds decorum, taste, chivalry, good table manners.

Cinema grew from amusement parks, fairs, shows, an "attraction" for the rubes. And, like calling to like, the movies still nurture a fascination for such places of low pleasure.

As he shot Touch of Evil in and around Los Angeles' Venice Beach on a handful of nights in the early spring of 1957, Orson Welles would bashfully drape those trashy, less cinematic elements of the Mediterranean counterfeit before him in a voguish noir frock coat; one that would, at once, revel in the inherent ghastliness of such a place while concealing its full absurdity from eyes that would never be able to handle the contradiction.

Some years later, fate would conspire to choose Curtis Harrington, a cross-dressing Poe fanatic, to fully capture “The Slum by the Sea” with all its ravaged whimsy set against the lyric humiliation of once-ostentatious digs and the ruined face of spent oil wealth. Singularly unembarrassed by what he saw, Harrington gave audiences a Venice Beach that Welles would not: the sun-dappled occult, the queer, the criminal; a true, flophouse-ridden glory bathed in the endless California sunlight.

Night Tide (1961) assembles a distinguished skid row where underworld docents by the dozen — murderers, perverts, soothsayers and sea witches — pop into being with dazzling efficiency. Picture one thousand elves rising with glee to the same, single-minded curatorial task and you'll have a sense of what is involved here. In other words, as a demiurgic force, Harrington does not emerge from nothingness. After two decades fruitlessly bashing his head against the avant-garde wall, our schlockmeister arriviste goes Hollywood — that is, any imaginable “Hollywood” rude enough to splotch him with flat soda or leave him smelling of hot gravel and exhaust fumes.

With its hinky cast — nonfictional witch, Marjorie Cameron; erstwhile muse to surrealist filmmaker Jean Cocteau, the undersung Babette who usually appears en travesti; and lecherous, booze-addled, fresh-faced Hollywood castoff Dennis Hopper — Night Tide invades the drive-in. A tarot reading at the film’s heart gives Marjorie Eaton her time to shine, traipsing into nickel-and-dime divination from her former life as a painter of Navajo religious ceremonies. Linda Lawson might have issued from an etching by Odilon Redon, with her raven locks and spiritual eyes, our resident sideshow mermaid. Not surprisingly and despite such gentle segues, the film itself traveled a rocky road from festivals to paying venues.

Despite the film’s scant $50,000 budget and somewhat dubious standing (after all, this was the director’s first attempt at feature filmmaking), Harrington captivates well-established eminences like cinematographer Floyd Crosby (Tabu) and composer David Raksin (Laura). Their contributions are keyed with great sensitivity to the film’s teasing invitations: “Do you want to live on a black and white Venice Beach boardwalk, have breakfast with a hot sailor and a hotter mermaid, hang with an old drunk captain and listen to the strange tales behind his morbid souvenirs?” It’s worth mentioning that Truman Capote, after catching a Times Square screening, adored Night Tide. We won’t ask what he was up to in a grind-house theater, but whatever it may have been, Mr. Capote encountered the movie in its ideal environment: equal parts sub-rosa poetry and grim

Mayo Methot: More Than You Know

The sad passing of Lauren Bacall [August 12, 2014], aged 89, leads to various melancholy reflections, among them the fact that the previous Mrs. Bogart, Mayo Methot, seems now completely forgotten, remembered only as a footnote labeled “mean drunk.”

Peter Lorre, it was said, once drolly offered to demonstrate what a volatile couple Humphrey and his first spouse were, sidling past them and uttering only the words “General MacArthur.” Within a minute of this verbal depth charge being released, Methot was clawing her husband’s face open while he attempted to club his better half unconscious with a whiskey glass. But when not engaged in such charming interplay, Methot was a riveting screen personality whose appeal is more or less diametrically opposite to that of her successor.

Phooey

His voice comes out of a secret hole between his eyes, that honking New Yawkese of Allen Jenkins – built like a barrel of pickles that fell off the truck on Pearl Street, always avid to be abused in knuckleheaded sidekick roles. Meanwhile, audiences remain free to unconsciously admire that desperate toehold in the coveted world of jobs and three squares a day. For Jenkins plays more than just a “good mug.”

Bezark

“Bezark” is 1930s underworld lingo for “woman”, equating with “pansy” when applied to men. Listen carefully and you’ll hear the word – sometimes pronounced “bee-zock” – in films such as The Mayor of Hell (1933), Me and my Gal (1932), and The Torrid Zone (1940). Special thanks to Richard Polt for hammering out “bezark” on several of his antique typewriters.

Letter by Blaise Cendrars

Jean Epstein, La Poésie d’aujourd’hui un nouvel état d’intelligence, Paris : La Sirène, 1921, pp. 213-5

The Poetry of Today, A New Mindset

Letter by Blaise Cendrars

Jean Epstein, you’re outlining the collective psychosis of the end of a generation rather than the more evolved psychosis of a few of us who already went through the stage that you point out. You see us from the backside, and like the assault troops with a white patch on the back of their uniform, we’ve passed the goal-line and shells from our side are landing smack on our kissers. Are you carefully taking stock of the former crisis as well as the beginning of the new one?

Hello, Molly

Molly Picon stopped growing when she was a kid and topped out at around four foot eight – four-eleven standing on her tiptoes, she liked to say. The biggest thing about her was her impish Betty Boop eyes. But she packed a lot of energy and spirit into that miniature package. She could and would do anything to amuse an audience – sing, dance, do a somersault, climb a rope, crack jokes, wear blackface or boy’s knickers. She played gamins, waifs, soubrettes well into her matronly years. The one thing she wouldn’t and maybe couldn’t do was to hide or even just tone down her essential Jewishness to appeal to the goys in the mainstream audience. It sets her apart from many other Jewish entertainers of her day. Whether she was performing in Yiddish or English, on Second Avenue or in Hollywood, there was never any question that Molly Picon was Jewish. Very Jewish.

She was born Malka Pyekoon on the Lower East Side in 1898, in a fourth-floor back bedroom of a tenement on Broome Street near Bowery. Her mother was a seamstress who’d escaped the pogroms near Kiev as one of a dozen children. Her father was an educated man from Warsaw who was never happy doing an immigrant’s menial labor in America, so he did as little as he could. He also turned out to have a previous wife back in Poland he’d never legally divorced. He drifted in and mostly out of Molly and her sister Helen’s lives. Decades later, when Molly became well-off and world famous, he’d drift back into hers, to borrow money.

Their mother and grandmother picked up and moved the girls to Philadelphia, where Mom became a seamstress at a Yiddish theater and took in boarders. Later she’d run a small grocery store. The story of how Molly got her start in show business – like many of the tales in her charming and irrepressibly schmaltzy memoir Molly! – is too good not to be true. When Molly was five her mother, who made all her daughters’ clothes out of odds and ends, stitched her up a fine outfit and took her on a trolley headed for amateur night at a burlesque theater, the Bijou. On the trolley a drunk challenged the little girl to show him her act. She sang and danced in the aisle. Charmed, he passed the hat and collected two dollars. At the Bijou the audience tossed pennies on the stage while she performed. She also won the first prize, a five dollar gold piece. Her grandmother was astonished at the ten dollars she’d earned – roughly a week’s wages for an adult worker. When her mother said she was going to start taking her around to all the amateur contests, her grandmother said forget the theaters, there weren’t enough in Philadelphia – just keep taking her on the trolley.

Boris Thomashefsky’s brother Mike ran Philadelphia’s Columbia Theatre. He soon put Molly and Helen in a Yiddish production of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Helen as Little Eva, Molly in blackface as Topsy. Molly, billed as Baby Margaret, continued to act through her childhood. She dropped out of high school in 1915 to tour small-time vaudeville in a female quartet, the Four Seasons. In Boston in 1918 she visited a Yiddish theater group who performed one night a week at the Grand Opera House, a large but no longer grand theater in the South End that staged wrestling and boxing the rest of the week. One of the young actors she met there was Muni Weisenfreund; ten years later he’d go to Hollywood and become Paul Muni.

Jacob Kalich, who ran the theater company, came (like Weisenfreund) from Galicia, a province on the Austro-Hungarian empire. He’d studied to be a rabbi but then fell in with traveling Yiddish theater troupes. He’d slipped into America without a passport and speaking no English in 1914. Kalich hired Molly away from the Seasons, they fell in love and were married the next year in the back room of her mother’s grocery store. According to Molly’s memoir, her mother stitched her wedding gown from a stage curtain.

Yonkel, as Molly called Kalich, wrote parts and whole plays specifically for his new wife. One was Yonkele, an operetta in which she wore boy’s clothes and sang, danced and did her somersaults as a kind of Yiddish Dennis the Menace. Kalich was unsuccessful in trying to get one of the Yiddish theaters on Second Avenue interested. On the Lower East Side as in American theater generally, leading ladies tended to be stately Lillian Russell grandes dames, not petite gamins in knickers.

After a child was stillborn in 1920 Kalich distracted Molly with a new project. They sailed for Europe. His plan was to make her a star (and improve her Yiddish) in the theaters there, then return in triumph. They started in Paris, where Yonkele was a hit, then toured it around Europe for two years. In her memoir she says they did three thousand performances, almost surely an exaggeration, but they did keep busy, and her star kept growing. She made her first Yiddish-themed silent films in Vienna starting in 1921, playing a sassy soubrette or a boy. When they were in Bucharest hundreds of university students shouting anti-Semitic slurs rioted in and outside of a theater where she was performing. They may have been put up to it by the Romanian National Theatre, which was losing business to Picon. It was time to come home.

Jews around Europe had been writing their American relations about the wonderful new star. Kalich’s plan had worked. By 1922 the Second Avenue Theatre near Second Street was happy to host Yonkele and anything else Kalich put together, as long as it had Picon in it – Gypsy Girl, The Circus Girl, Schmendrick, Oy is dus a Madel (Oh, What a Girl!). Picon played to houses packed not just with Yiddish-speaking Lower East Siders but with celebrities like Greta Garbo, Mayor Jimmy Walker, Albert Einstein and D. W. Griffith. Griffith was on the downside of a long career by then and tried, without success, to raise money for a film starring Picon. Flo Ziegfeld and his wife Billie Burke (the good witch in Wizard of Oz) came over from Broadway to see Molly perform. Afterward, Yonkel and Molly took them to a Jewish restaurant, where the waiter covered the table with plates of pickles, sauerkraut, fried steak, radishes slathered in schmaltz. The very goy Burke asked the waiter if she might have some vegetables. What, he snorted, pickles and sauerkraut aren’t vegetables?

Picon was such a star that Kalich got the idea of renaming the theater the Molly Picon Theatre. When their packed performance schedule there permitted, they toured Yiddish theaters around the country. Later, Jews who had fled Eastern Europe for South America organized a tour for her there. She would also tour South Africa.

She returned to vaudeville in a big way, headlining at the Palace in Times Square with Sophie Tucker. Picon sang half her songs in English, Tucker sang half of hers in Yiddish, and they triumphed. When Picon played the Palace in Chicago, Al Capone (who had started out on the Lower East Side himself) bought out the first three rows. After the show he took Picon and Kalich out to dinner. At his request she sang “The Rabbi’s Melody” (a big hit on Second Avenue) and, she claims, he “cried like a baby.” For the rest of her career she introduced it as “the song that made Al Capone cry.”

The Immaculate Contradiction of Barbara Steele

Any serious contemplation of the true extent of Barbara Steele’s gifts can reach only one, inevitable conclusion. There is no question of her being a good, often great, screen presence, but to say that in every meaningful sense her abilities end there, is to admit one thing: she is not highly skilled as an “actress.”

To be fair, the experience gained as part of the stable of starlets of the J. Arthur Rank Organisation is no equivalent to a season or two at the Moscow Art Theatre. But what she emits from the screen is far more important — at least to me — though precisely what I’ve been pursuing for the past twenty years, will probably always remain a mystery.

What I can identify is the concrete workings of Barbara Steele’s magic.

“I recognise the expression on fans, a kind of sexual melting,” says Steele herself, though she would never admit that — from the denizens of mom’s basement to intellectuals performing their cleverness — her screen-image reaches across decades to find acolytes who liquefy on the spot. Here, a complete list of the various symptoms defining “magic” must include Andre Breton’s dream, which Steele brings to fruition six years before his death, thereby making the Surrealist impresario a bonafide prophet: "Beauty will be CONVULSIVE or will not be at all."

Nor does Jean-Paul Török ooze into nothingness before the lightning flash Black Sunday (1960).

Instead, he spasms for us all.

When aesthetic admiration is absolutely fused with desire and terror, it "blacks out”…. Where are your vaunted intelligence and your cultivated taste when everything in you freezes and is fascinated before the revelations of the utmost horror? Beneath the flowing robe of this young woman with so beautiful a countenance there appear, distinctly, the tatters of a skeleton. Is she any less desirable?

Peep Shows and Palaces

For all their immense impact on popular culture, movies began humbly, and for a while it looked like they might never be more than a minor amusement. The first movies shown to the American public, Edison’s Kinetographs, appeared in the early 1890s. Because neither Edison nor anyone else had yet invented viable projectors, the first short film loops weren’t shown on screens. One viewer at a time dropped a penny in the Kinetoscope peep show machine, turned the crank and watched the one-minute loop through the eyepiece. The peep show’s appeal was as limited as its technology, and it never caught on outside of penny arcades.

Projectors came along soon enough anyway. Interestingly, given film’s later impact on live performance, the first commercial screening of a projected movie in the U.S. was in a vaudeville theater: Koster and Bial’s Music Hall on Thirty-Fourth Street, where Macy’s is now, in 1896. Other vaudeville theaters followed suit. At first they screened films as what were called “chasers” – acts at the end of the bill that were so bad or boring they cleared the house, making way for the next paying customers and the next cycle of performers. Because the films often just showed vaudeville acts recreated in silent pantomime, audiences shrugged and walked out on them.

As soon as projectors were developed, small-time showmen were traveling the country with them. They’d come into a town, identify a willing merchant, and set up a “store show” after regular business hours, screening their short films to the accompaniment of a local pianist, with maybe some local live acts as well.

Frankie Darro: No Strings

He was the voice of Lampwick in Walt Disney’s Pinnochio (1940), the bad boy who gets turned into a donkey on Pleasure Island, maybe the most upsetting scene in any Disney cartoon. He was one of two actors inside Robbie the Robot in Forbidden Planet (1956), small enough to fit inside the costume. He played lots of jockeys and Dead End Kids and Bowery Boys, and he made scores of low-budget westerns. He was menaced by Boris Karloff in The Mad Genius (1931). He was a man in a leg cast hoisted up in his hospital bed in Blake Edwards’s The Perfect Furlough (1958) and he examined Cary Grant’s posterior in Edwards’s Operation Petticoat (1959). As an adorable, Jackie Coogan-like little boy, he got a laugh asking a woman to dance in Flesh and the Devil (1927) right before Greta Garbo waltzes away with John Gilbert. He was a son to Marie Dressler’s Tugboat Annie. On Red Skelton’s TV show in the 1950s, he did an old lady routine that routinely brought down the house. Frankie Darro had a long and varied career. And in 1933, in two films, Mayor of Hell and William Wellman’s Wild Boys of the Road, Darro is an actor with a capacity for greatness, if anyone had bothered to notice.

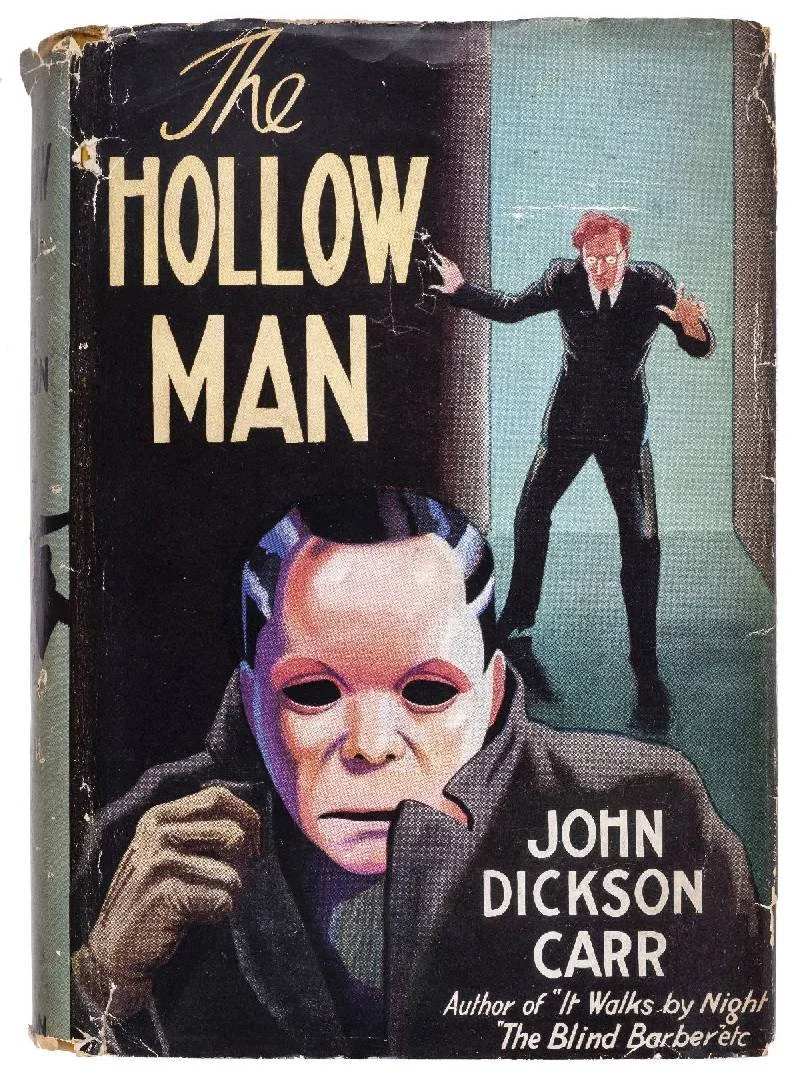

John Dickson Carr

John Dickson Carr was an American who moved to Britain in the thirties and became an overly prolific writer of gentleman sleuth type "cosy crime" mysteries. He sold so many he was compelled to split himself in two, giving off an alternate persona as Carter Dixon, a rather transparent ruse unworthy of the convoluted and unlikely twists his tales hang on.

Carr/Dixon's big thing was the impossible crime or locked-room mystery. He focussed on it obsessively, autistically, to the exclusion of all else. Probably only half of his plots would have any kind of chance of being enacted in reality, so prospective murderers need not look to him for pointers: in one book he has his lead detective proclaim, "We are not concerned with whether the thing would be done, only if it could be done." But even given the occasional disappointing denouement, there is much to commend this oddball.

Edna May Oliver

She’s got very little chin, this Edna May Oliver dame. So it kind of looks like her neck just sort of swelled up a little like a semi-inflated balloon, instead of being a head. You realise how important a chin is, a way for a head to identify itself. With so little chin, she has to rely more on stuff like eyes, nose and mouth to convince us she has a head. And those organs do a lot of hard and important work and so finally, we do believe we are indeed looking at a dame with a head.

We’re not necessarily so sure it’s a dame’s head, though. Not that she’s exactly mannish, despite the elongated Olive Oyl figure and the air of sharp, snappish authority. That air is maintained by the imperious, far-back-in-the-throat clarinet voice, which carries a quality of outraged dignity no matter what other emotions its conveying.

But to return to the head. It might be that a Masai warrior has donned a moose head and done a lot of limbering-up excercises to cultivate a supreme looseness of limb. A loose Masai moose with limbered limbs, if you get me. The lips, you see, drawn back in exasperation and tightening over the teeth like inner tubes under strain, have a very moose-like quality. The mouth is as wide as the head is long. The corners have to curve up to prevent them escaping the outside of the face altogether, which would be a disaster for all of us.

The eyes, rolling and gleaming, have the marble-like sheen of most eyes you see in moose heads. An unexpectedly sympathetic look, I must say.

Annals of Censorship #1

Mr. J. L. Warner,

Warner Bros. Studios,

Burbank, California

Dear Mr. Warner:

We have read the final script of your production, WILD BOYS OF THE ROAD, and have given it very careful consideration. It seems to us that it contains several major problems to which some further consideration should be given both from the standpoint of the Code and censorship.

First we feel that the characterization of Aunt Carrie's residence as a house of prostitution is very questionable under the Code and dangerous with regard to official censorship. Consequently, it would be wise to change the nature of these scenes radically and indicate, if possible, that Aunt Carrie runs a speakeasy or that she is implicated in any other kind of a racket which might make her liable to arrest. If such a change were made, all the story necessities would be saved and, at the same time, a very dangerous situation would be avoided.