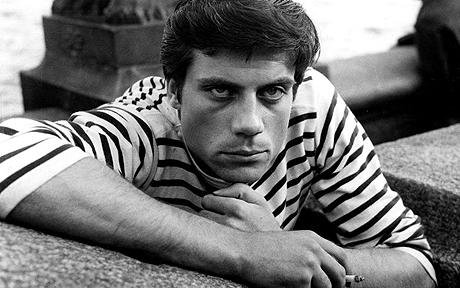

The Unquiet Man

"I know what you're going to do," director Richard Lester told actor Oliver Reed before a take, "You're going to whisper three lines and shout the fourth." And indeed, Reed, nephew of the esteemed filmmaker Carol (The Third Man) Reed, would boast of being "the sound man's enemy" due to his unpredictable delivery: because sometimes, in fact, it might be the third, or second, or first line that got shouted.

The Clown Prince of Slavery

In 1820, Congress forbade Americans from participating in the international slave trade, making slave-running an act of piracy, a hanging offense. It was an easy gesture. America had no need to import more slaves; between 1790 and the start of the Civil War the domestic slave population in the U.S. soared from around seven hundred thousand to over four million. Conditions were the opposite in Cuba and Brazil, however, where slaves working on the vast sugar plantations and in the gold mines perished at appalling rates. Constantly hungry for new slaves from Africa, Cuba and Brazil bought at least two million in the first half of the nineteenth century. Running slaves to those countries was an extremely lucrative business that Americans found irresistible, and the government did almost nothing to enforce the ban. In the whole long history of the transatlantic slave trade, only one American sea captain ever swung for it, and that wasn’t until the very end of the practice, in 1862, when the Lincoln administration chose to make an example of him.

To evade the British and U.S. warships trying to stop them, slave-runners needed fast ships. Launched from a Long Island shipyard in 1857, the Wanderer was the most impressive racing yacht of its time. With its sleek, revolutionary design it could make an astounding twenty knots, outrunning any ship at sea, including steamers. It was also sumptuously appointed, because it was a rich man’s toy. The owner, Colonel John Johnson, was a member of the New York Yacht Club. He was not a New Yorker but a Louisianan, owner of a cotton plantation. In 1858 Johnson sold the Wanderer to another Southerner, a Charleston man named William Corrie. Corrie was acting as a front for yet another Southerner with New York connections: Charles Augustus Lafayette Lamar.

Night Tide

Canonical stature is both fragile and contingent, and that’s why powerful institutions seek to shore up the various canons with rankings and plaudits. We’ll play along by asserting that one of our favorite “B” movies was originally screened by Henri Langlois at the Cinematheque française with Georges Franju in attendance. Night Tide (1961) was an unlikely contender for this particular honor—shot guerrilla-style on an estimated $50,000 budget, and intended, at least by its distributors, for a wider, less demanding audience seeking mostly air-conditioned escapism.

Arc de Triomphe

Thanks, Richard Polt, for immortalizing this poem on your antique typewriter.

A Paean to Witches

I first read Jules Michelet’s Satanism and Witchcraft 50 years ago, judging from a bookmark ripped from the corner of a now-defunct Philadelphia daily. I still have the same ratty Citadel paperback, the red backing turned pink and held in place with packing tape. (It’s now available from Kensington Publishing.)

Michelet was perhaps the leading historian of 19th-century France, a man who spent 30 years putting together a multi-volume history of his country – then turned out a book a year compiled from the leftover notes. Satanism was 1862’s contribution and, from all accounts, his most personal, decidedly eccentric, piece of work. For long is was also his only title in print in English.

What is history? That’s been a topic of academic debate over at least the last half century, during which time a trend developed away from chronicling the doings of kings and other big boys and toward finding out what the “real people” were up to.

37 Views of Percy Helton

Percy Helton was a short, chubby, balding, hunchbacked actor with a raspy voice and an air of sinister decay. I have referred to him as the “orangotoad” and the “sex goblin” based on his work in Wicked Woman (1953) but really, there is no shortage of evocative descriptors for such a strange and unsettling specimen of humanity. Often “inexplicably cast as human beings,” as my friend Randy Cook put it, Helton truly excelled when playing creepy types who got you wondering, like the sleazy coroner in Kiss Me Deadly (1955), who you just know gets up to inappropriate convivialities with his deceased clientele the moment the camera looks away.

Here are some things you can call Percy next time he pops up. There are exactly thirty-seven of them: count ‘em and see!

The fanged nerf ball

Cushion with dentures

Putty homunculus

Cherub with radiation sickness

Aged embryo

Jiminy Rictus

Stray fragment of Orly Cathedral

A sandwich made from a bap and a length of tongue

A buttock with stab-wounds

Paul Williams’ wicked grandfather

The skin balloon

A chubby skull

Lipless chimp

Flayed opossum

Man-gerbil telepod mishap

Uncle Unctious

Bulbous insinuator

A sack of rats in jelly

The hamphibian

Creepy dweeb foetus

Skulking pupa

Puffy scarabus

The incarnate gloat

Rasping jackanapes

Crapulent whiner

The puppet nobody wanted to put their hand in

The dollop

Old wormy-hump

The crouching fumbler

The clingy dribbler

The nameless guzzler

The grubbly nuzzler

Squidgy hummock

Throaty fleshapoid

The seedy wheedler

The soiled bulge

Toilet plop embodiment

The greasy dumpling

The clammy pudding

Prematurely shelled crustacean

A dying child’s unfinished drawing of Charles Coburn

by David Cairns

Melville, or the ambiguities

I’m part way through The Piazza Tales, a collection of Herman Melville’s longer short fiction – or shorter long fiction, depending on how you look at it – what might, these days, be considered “novelettes” or “novellas” or some similar hideous term. Some are old friends, like “Bartleby,” others are new to me. But there’s one unifying thread, as there is to all of Melville:

Space, Speed, Revelation and Time: Jean Epstein’s Early Film Theory

In October 1921, the prestigious Parisian avant-garde publishing house Éditions de la Sirène released a small volume of essays and poems–what the French call a plaquette–entitled Bonjour Cinéma. The book’s most immediately apparent feature was its diminutive scale, barely larger than the palm of a hand, that recalled one of the programs handed out in prestigious movie theaters of the day. On the reddish-brown field of its strikingly designed, ultra-“modern” cover, slim white letters spelled out the word “Bonjour,” calling to mind the placards welcoming contemporary audiences at the start of a film program. Superimposed on this background was a large letter “C,” and from its center emanated a white triangular shape, as if to represent a projector casting its beam toward a screen lying beyond the cover’s right edge. In this graphic “light,” the letters “i-n-e-m-a” floated, parole in libertà fashion, across the surface, conjuring up the associative realms of “life” and “soul” that frequently circulated through the thinking about films in France during the 1920s and beyond. This lively graphic image also cleverly disclosed the book’s aspirations: nothing less than to cast light on the cinema, the popular art that, more than any other, fascinated the generation of artists and intellectuals who came of age during the decade following World War I.

Harry Langdon or The Malady of Sleep

This 1929 article by Paul Gilson, something of a forgotten classic in France, was published in the third issue of Jean George Auriol’s Du Cinéma (which would become the better known La Revue du Cinéma with the next issue) to coincide with the French release of Harry Langdon’s underappreciated masterpiece Three’s a Crowd. The magazine, close to various avant-garde circles, featured everything from screenplays to reportages to reviews, testifies to the effervescent, and relatively little known, film culture in Paris at the time. For those familiar with the bland, descriptive write-ups of most movie reviews of the era, this piece comes off as an exhilarating exercise in a deliriously subjective, free-form style of poetic film writing that is more inspired by the film than about it — an approach that, to this day, remains largely unexplored.

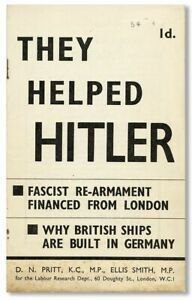

They Always Help Hitler

In a 1936 pamphlet entitled THEY HELPED HITLER, British Labor laments continued financial support of Britain’s banking establishment for the Nazi war machine: hundreds upon hundreds of thousands of pounds diverted from domestic public works projects, which might have served the urgent human need of the great British public, flowing right into the pocket of Thyssen and Krupp, to manufacture the very instruments of death that would lay waste to whole chunks of the country just a few years later.

In this light, one can see how Sen. Bernie Sanders’ allegiance to the 50 weapons manufacturers supporting him will, eventually, take a nasty turn. For, despite whatever you may have been told, children, it is axiomatic that when Western elites use the term “national security” they are not referring to you, nor is it the substantive, everyday security of your life that they have in mind.

The true, downright scriptural meaning of this overused and under-understood phrase is merely securing the state’s ability to spread wanton, near unimaginable violence throughout the globe, while controlling the resources required to do so without restraint. You – which is to say you, me, and every other sentient being on earth who isn’t a flesh-eating deep-state sociopath – matter to these tribunes of our National Security state only insofar as you are useful for one of those base and utterly diabolical purposes.

THEY HELPED HITLER calls to mind a horrible development.

In mid-May, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Bernie Sanders, Jamaal Bowman, Cori Bush, Rashida Tlaib and Ilhan Omar voted to put $17B in the pockets of weapons manufacturers. Keep in mind that these DSA members (a slight exception, Omar is DSA-adjacent) support America's proxy war against Russia to the tune of $40B, serious money given that poverty's on the uptick. What's up, Socialism?

by a couple of Chiselers

“Watertown”: A Frank Look at Lost Hope

I’ve never been a Frank Sinatra fan (that’s why I have to wear a disguise in public), but way back when, Jim Knipfel made me a worn-down tape copy of the Watertown album from 1969. It’s not like anything else Sinatra did – not like anything anyone else did either – and it fascinated me from the first listen.

I bought the CD remaster recently (without the unfortunate and spurious later addition of “Lady Day”), and I’m still hooked. But it’s not something I can listen to in just any mood. It’s not something anyone should listen to while depressed or going through one of life’s ordeals.

It’s pigeonholed as a “concept” album, but it’s more like a short story set to music. You don’t know where it’s headed in the first couple tracks, and it takes awhile to get the whole picture. It’s mostly an interior monologue by a deserted husband, left to care for his two young sons, yearning for healing, filled with a loss that seldom consciously penetrates an otherwise unpeopled emptiness.

Watertown was a commercial bust for Sinatra, his only album that didn’t make Billboard’s top 100. Some have suggested that the timing was wrong – at the end of the upbeat ‘60s, a “downer” album lad to land like a lead duck.

But no, it isn’t that. This album would never have been popular, never will be popular. It’s simply the bleakest look at a slice of personal life that’s ever been recorded.

Izzy and Moe

From the moment Prohibition went into effect in January 1920, New Yorkers from top to bottom, from the mayor to the immigrant laborer, from its hoodlums to its largely Irish constabulary, set out to ignore the new law, get around it, or profit from it in some way.

The market for both large, industrial stills and small home models boomed. New York newspapers ran ads for one-gallon home stills, and hardware stores displayed them in their windows. The shelves of any public library held books and even helpful government pamphlets on how to use them. As every backwoods moonshiner knew, stills sometimes blow up, making them dangerous appliances to have cooking away in apartments all over New York. Periodically through the 1920s a still explosion would make the news, including one in a West Eleventh Street kitchen that killed the owner’s baby son.