Joseph Moncure March Writes the Poem of the Century

In the spring of 1926, following what he called “…a series of brutal altercations with Harold Ross,” Joseph Moncure March quit his job as the (very first!) managing editor of The New Yorker. He moved into a depressing 4th floor walkup on 14th Street in Greenwich Village. He was all but broke. His father staked him enough money to get through the summer, which he (of course!) spent writing a book-length piece of narrative verse—rhyming!—about “a lot of people getting drunk at a party.”

He had the first two lines, which had popped into his head, apropos of nothing, a few months earlier:

‘Queenie was a blonde, and her age stood still,

And she danced twice a day in vaudeville.’

Ophelia by the Yard

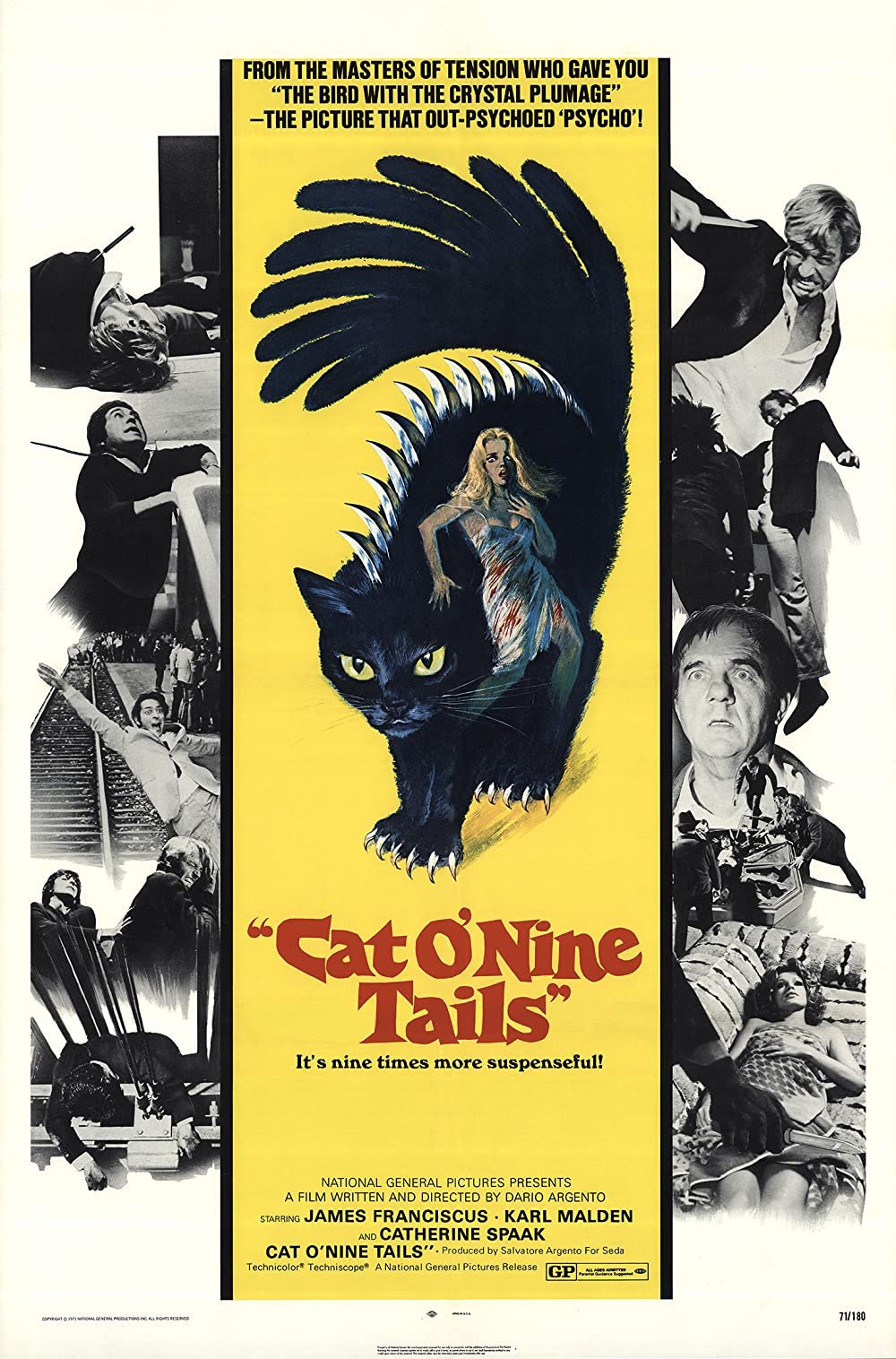

Cobwebbed passages and wax-encrusted candelabra, dungeons festooned with wrist manacles, an iron maiden in every niche, carpets of dry ice fog, dead twig forests, painted hilltop castles, secret doorways through fireplaces or behind beds (both portals of hot passion), crypts, gloomy servants, cracking thunder and flashes of lightning, inexplicably tinted light sources, candles impossibly casting their own shadows, rubber bats on wires, grand staircases, long dining tables, huge doors with prodigiously pendulous knockers to rival anything in Hollywood.

Here was the precise moment — and it was nothing if not inevitable — when the darkness of horror film, both visible and inherent, leapt from the gothic toy box now joined by a no less disconcerting array of color. The best, brightest, sweetest, and most dazzling red-blooded palette that journeyman Italian cinematographers could coax from those tired cameras. Color, both its commercial necessity as well as all it promised the eye, would hereafter re-imagine the genre’s possibilities, in Italy and, gradually, everywhere else.

Death in Venice, California

On February 1, 1963, Night Tide lapped like an expressionist wave against the screens of American drive-ins and art houses, not to mention the Times Square grind house where Truman Capote saw, and absolutely treasured, Curtis Harrington’s 1961 opus. Night Tide rolls in with the satiny force of its leading lady, Linda Lawson, whose breathy voice expresses alien intensity lurking behind an opaque curtain of melancholia.

It had spent three years languishing in the can when distributor Roger Corman smuggled the unlikely masterwork into public consciousness, another of his now legendary mitzvahs to art. Throughout Night Tide, a strangely hushed invitation lingers in the air: "Come live above a merry-go-round, have breakfast with a hot sailor and an even hotter mermaid, spend hours with an old drunk captain, listening to the strange tales behind the morbid souvenirs of his life.”

Zoetic Leaves

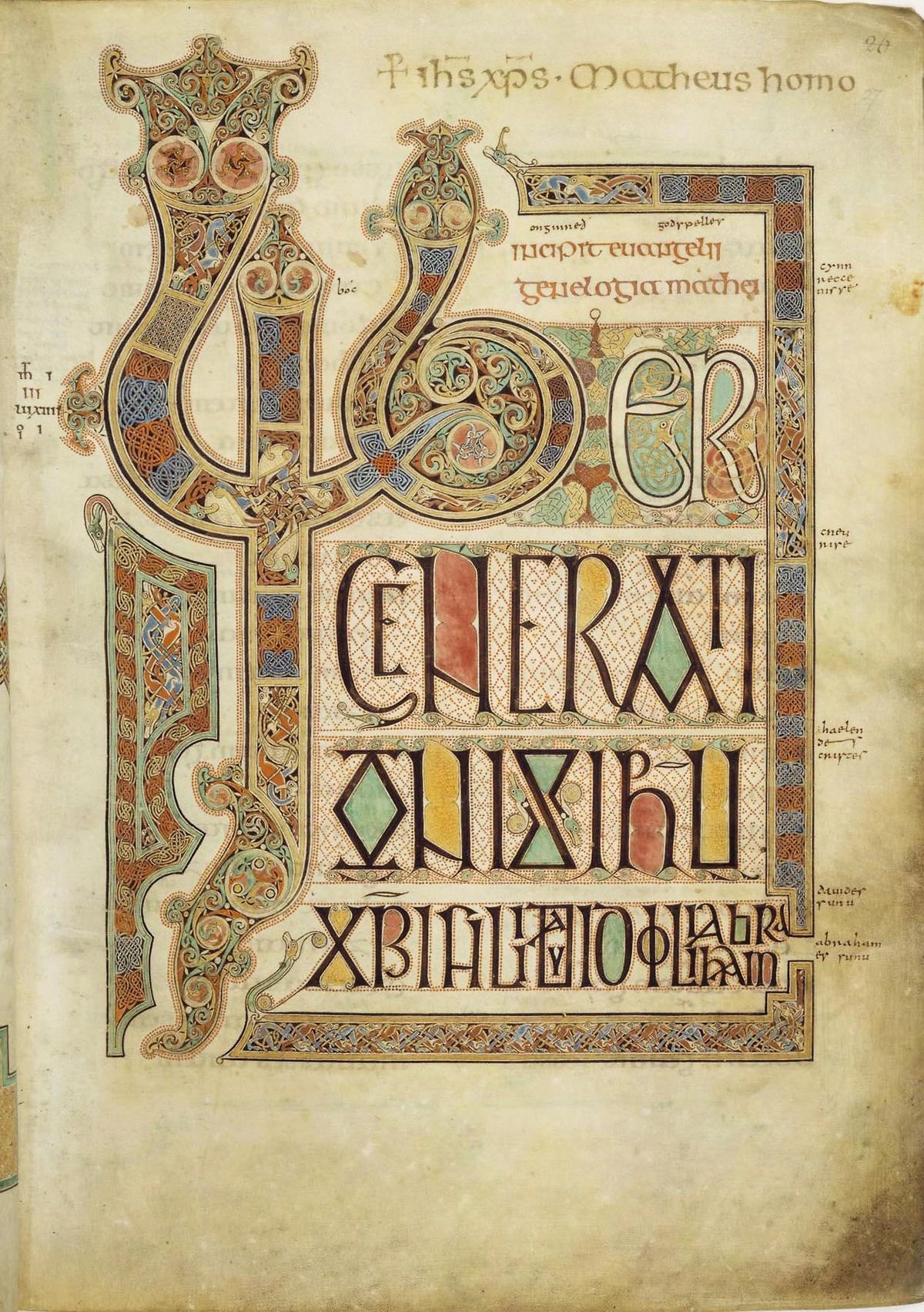

It is the custom of illuminated manuscripts to transform sacred words into shimmering icons which break, easily, beyond the sensory limitations of simple text, rendering ordinary letters into evocative, animate visual forms that invite the eye to linger at the brink of transcendence, rather than standing at a distance, remote and unyielding, daring to be comprehended, accepted, believed. Strange and barely recognizable wildlife appears on vellum leaves, creatures that wind and unwind in ceaseless whirlpools of bejeweled abstraction. Or, if you prefer, these are the animated exoskeletons of snakes, dragons and waterbirds — Celtic and Germanic obsessions meeting the Apostles of Christendom. Emerging in the British Isles between 500–900 C.E., The Lindisfarne Gospels provide an arena, lapidary and starlit, where paganism devours Christianity while also birthing the religion anew into “motion pictures”.

Put simply, movies are books made from light, zoetic leaves and letters that move beyond their trellis, leaving us to decipher a purely visual enigma; one all the more impossible to contain within mortal consciousness because the light of this steadfastly irrational art has swallowed up the text.

There are those, however few in number, who have decoded this cryptic iconography, but mysteries remain, not unlike those mysteries — strange, delved, bewildering — contained within the gospels.

They are mysteries that urge upon us a wholly radical reconsideration of silent film; of the book in film, of whispering pages; pages fluttering like leaves. Of Stan Brakhage, who gave us a series of works entitled The Book of Film and otherwise seemed incapable of regarding the universe independent of its sensual properties. Of Hollis Frampton and Peter Greenaway. Certainly of Robert Beavers, who incorporates the sound and motion of turning pages — placed in relationships and analogies with other actions — and the moving of birds wings in flight. This is not the middlebrow idea of film as purely narrative-bearing text. It is Mallarme’s concept of the book, the Proustian notion of the book. It is its ultimate realization, par excellence, and by far the most apposite. The films of David Gatten, which deeply engage with the idea of the book, the history of books. These are works that require different modalities of reading/touching words and saccadic rhythms involving different velocities of hyphenation and partial retention and compound phrases through the softest of collisions.

A Genesis Out of Light

Would it be preposterous to argue that movies are essentially projected books, books made out of light? Even weirder, let’s entertain the idea that Jules Verne’s science-fiction imagery, which finds itself transfigured early in the development of cinema, is not alone: the audience — you, me and everyone watching — dissolves into moving illustrations. “Motion pictures”. A horrifying thought if we “foolishly” believe that our three-dimensional selves could squish, flatten (and like it!).

Dating at least as far back as Georges Méliès, the cinema of bodily transformation did not necessarily equate with “horror” per se. The horror film was eventually codified as genre from the cinema of bizarre attractions exemplified by Lon Chaney, master of grotesque makeups and bodily contortions, but in the early cinema it was standard procedure to have one's detached head inflated to fill the room (The Man with the India Rubber Head) or multiplied into a row of bodiless noggins, singing or rather mouthing in harmony (The Four Troublesome Heads). Then came Nosferatu, preordained to shimmer on-screen. Vampires, immortals of the night, slain by sunlight, rose out their tombs in the movie theaters of the 1920s and never returned. They sit next to us in the dark, having ceded the power of hypnotism to the glowing screen itself. Photochemical vagaries invariably allow movie darkness to behave in uncanny ways; as if the physical properties of film followed no rules, and thus invited us to accept its essential anarchy without question. Before us, the darkness GLOWS.

Celine: His Life and Correspondence

In a well-known essay about Voyage au bout de la nuit, Leon Trotsky wrote that its author, French writer Louis-Ferdinand Céline “walked into great literature as other men walk into their own homes.” Indeed, Voyage was a revolutionary book, both in terms of content and of style, a book that immediately turned literature upside down. Written in a popular and colloquial language, it presents a dark and pessimistic vision of mankind as well as a nihilistic philosophy that drastically changed not only the way many novelists wrote, but also what they wrote. In France, traditional academic literature became practically obsolete overnight with the publication of Voyage while in the United States, several generations of writers owe a tremendous debt to Céline and his novel.

Céline wrote other books, especially Mort à crédit, the two volumes of Guignol’s Band and of Féerie pour une autre fois, D’un château l’autre, Nord and Rigodon, in which he went further in his experimentations with style and recounted darker and darker adventures in a growing atmosphere of chaos, madness and paranoia. Today Céline is almost unanimously considered one of the two greatest and most influential French novelists of the twentieth-century, along with Marcel Proust, and one of the giants of modern literature.

In fact, in the title of one of the first books devoted to Céline, American critic Milton Hindus used the noun “giant” to describe him, but modified it with the adjective “crippled.” That title, Céline: the Crippled Giant, was partly the result of an unfortunate encounter between the two men, but it also reflected the ambiguous attitude of Hindus, who was Jewish, toward Céline, then in exile in Denmark as a consequence of the polemical and strongly antisemitic pamphlets he wrote between 1937 and 1941, Bagatelles pour un massacre, L’École des cadavres and Les Beaux draps. Although he justified his behavior and his antisemitism in particular by his desire to prevent a new war and although he never actively collaborated with the Germans, Céline saw his reputation irremediably tarnished by those books.

Céline, the pseudonym of Louis Ferdinand Destouches (1894-1961), was not just a writer. He was very much involved in some of the major events of the first part of the twentieth century, notably the two world wars. He fought and was wounded in the first one while his political writings prior and during the second one forced him to flee to Sigmaringen with the most notorious collaborationists and the members of the Vichy regime before a grueling trip took him to Denmark where he was imprisoned for over a year and remained in exile until 1951. In addition, his extensive travels on three continents, mainly as a hygienist with the League of Nations, allowed him to witness the effects of colonialism in Africa and those of capitalism in the United States as well as the rise of the Nazis in Germany. Finally, as a medical doctor who worked with the poor and the destitute, he became intimately familiar with human misery and suffering.

Women of Letters

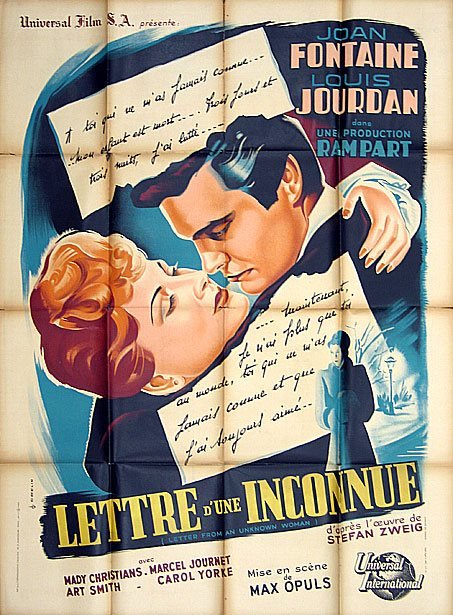

The first time I saw Letter from an Unknown Woman, I admired its craft and atmosphere but hated the story, about a woman who wastes her life in abject devotion to an unworthy man. A decade later I saw the film again, and found it as different as the heroine finds her beloved after ten years. Now it was not a tale of unrequited love, but a devastating anatomy of the illusions that lie at the heart of romance and even at the heart of our identities. The self-sacrificing woman and the self-absorbed cad both throw their lives away on false ideals, but their lives still have weight and beauty—so even do their ideals.

On Time and Cinema

“Time” is the concept that is so often overlooked in quick discussions of motion pictures and the cinematic experience. Movement, light, sound, and narrative all come to mind when we think about cinema, but time is not, probably because we are immersed in it, as are films. But this is to miss the central fact of cinema, that like music it is durational, with a pace and audible focus that is controlled by the composer of music, and by the film-maker (or to be more precise, a film editor).

In a narrative film our sense of time is usually dominated by the pressures of the story. In a film by Alfred Hitchcock this is not the case, because he uses time as a controlling element of suspense. We can feel the second hand of a clock ticking towards a moment of resolution. Time becomes dense, tangible. Hitchcock is not alone in this. Michael Snow and Stan Brakhage and Bruce Conner and Maya Deren and Howard Hawks and John Boorman (to name only a few) did this too.

In 1973 I had an early, and curiously mistaken, stumble over the sequential nature of time. At a conference in Buffalo Jonas Mekas showed Jerome Hill’s autobiographical Film Portrait. Near the end of the film Hill discusses, and shows us, how film depicts time. We see his film editing equipment, with reels to the left and the right, and he points to one set of reels of film as “past” and the other as “future.”

To underline what we have just seen he says on the soundtrack: “At the beginning of this film we were talking about time—time past and time future… The creation of the artist.” And then a summary statement, “Through cinema time is an island.” But a year ago I was able to consult Hill’s production script, and there found that he wrote “Time is annihilated.” On the soundtrack of the finished film it is hard to distinguish “an island” and “annihilated” but in a fundamental sense it does not matter. Both are declarations that in cinema time is not irrevocable, not eternally fixed, but something that can be manipulated, created by the artist.

By Robert A. Haller

The Riddle of Harry Stephen Keeler

When I first left Philadelphia in 1990, I thought back over all the people I’d known there, and realized much to my amazement that they all knew one another somehow, even if only in passing, and that I had nothing to do with it—everyone knew everyone through some other channel. There were writers, musicians, filmmakers and visual artists, most of whom I met through my work at a local alternative weekly. Given how small and insular Philly’s creative community was in the late ’80s, maybe it’s not so shocking they would come to know each other. But there were others in the mix, too—bartenders, publicists, club owners, dealers, journalists, waiters, academics, witches, common drunks, museum directors and political extremists. And they all knew each other.

It was an amazing web of characters. I took some time and backtracked through all the coincidental encounters with this and that person, how those lead to these others, then still others, until I had the whole, rambling picture of all these unlikely acquaintances and how they were tied together. Once I’d saw the finished puzzle and laid it all out on a large piece of cork board with pushpins and different colored thread to signify different paths of connection, I started thinking it might be an interesting tack to use in a book—knowing the singular picture at the end before starting, then going back to the beginning and tracing out the whole twisty web, coincidence after coincidence, until some final big revelation.

Well, I’m too lazy to put that much work into anything, so instead I decided to write silly meandering books with plenty of meaningless coincidences and bizarre, unlikely twists of their own, all made up on the fly as I went along.

Whenever anyone asks me to name my literary influences (and granted no one has in awhile) I always trot out the same tired litany of respectable forebears: Mr. Pynchon, Celine, Henry Miller, Dostoevsky, Vonnegut, James Thurber, Jim Thompson and the like.

While all that remains true, had I read anything by Harry Stephen Keeler before I fell into the unwholesome business of writing novels, I would have, without hesitation, cited him as a primary literary influence. Perhaps the one and only true literary influence on what I ended up doing. But I hadn’t read anything by him. In fact, I never read anything by Keeler prior to the end of 2021. I’d first heard of Keeler about a decade ago, and more or less knew what sorts of things he was up to, at least in very broad strokes. It all sounded interesting and right up my alley, but I simply never got around to reading him. If you haven’t heard of him, don’t worry, because nobody has. He’s kind of like the W. Lee Wilder of American letters, and just as forgotten.

One of the things that prevented me from reading him a decade back was the simple fact none of his books were available in digital form. In a blink though, and not that long ago, there were dozens of Keeler eBooks out there. I’ve since consumed five or six of his 50-plus novels, and I’m not sure when I’ll be able to stop. I hadn’t even finished the first one I picked up, The Green Jade Hand (1930), when I found myself thinking, “everything I’ve done I’ve lifted from Keeler.” In fact, everything I wanted to do, even if I haven’t done it yet, and even if there was no way I could have realized it, I lifted from Keeler.

Keeler’s story takes some telling.

He was a prolific pulp novelist who worked from the mid-1910s through the early ’60s. Although he published the occasional sci fi novel or Western, mysteries made up the lion’s share of his output, but mysteries unlike any other. The adjective “quite utterly insane” comes to mind.

Subliminal Faces in Liminal Spaces

1930s movie trailers were slapped together by monkeys with optical printers: scenery and character faces regularly explode with incoming images in fancy "wipes" which serve no purpose except to make the transitions energetic and to advertise the lack of continuity. Freeze the frame and the liminal moment becomes nightmarish, like the surreal effects of Max Ernst's decalcomania or William Burroughs' fold-in technique. Warring images form photomontages as impossible to process as a gunshot to the head.

Marjorie Rambeau: The Trouper

One of J.M. Barrie’s “half hours” of diamantine dramatic compression, Rosalind, gives its lead actress the irresistible opportunity to play an actress playing an actress. Apparently sunk in the doughy delights of middle age, she takes in a rain-soaked hiker who turns out to be an admirer of the “daughter” whose photo adorns her mantlepiece, the actress Beatrice Page. She reveals that she is the daughter, on holiday from the demands of the stage that have kept her alone and eternally twenty-nine: “Blame the pitiless public that has made me what I am. I am their slave and their plaything, and when I please them they fling me nuts.” At this point a telegram from the theater summons her to rescue a flagging season by reviving her infallible Rosalind in As You Like It, and she plods off to prepare to catch the London express. Her young swain manfully pleads through the door to rescue her from her treadmill and be a support to her middle age. Sensation! Through the door swoops a slim, sparkling, refurbished Beatrice Page, champing to hit the boards again: “The stage is waiting, the audience is calling, and up goes the curtain. Oh my public, my little dears, come and foot it again in the forest, and tuck away your double chins. … They are my slaves and my playthings, and I toss them nuts.” What actress could resist?

Marjorie Rambeau is probably most familiar to us today in her Pre-Code incarnation as a yowling bag, with or without heart of gold. She’s Annie in HER MAN, her runover round heels moving just ahead of the barroom mop, turned back by the U.S. authorities as she attempts to leave her Havana redlight haunts — “Say,” she sasses them, fatalism with hand on hip, “I got a roundtrip ticket.” She’s Bella in MIN AND BILL, a less benevolent waterfront kewpie, wallowing in Wallace Beery’s lap and threatening the happiness of the daughter she abandoned, until Marie Dressler fixes her wagon. She’s Flossie in MAN’S CASTLE, saving a fragile couple from denunciation by a stool pigeon: “Aw, this ain’t murder … this is just housecleanin’.”

Clobberin’ Time

In the heyday of comic books from 1930s through the ‘60s – what pop historians call comics’ golden and silver ages – fans might have been surprised to learn that many of their heroes and superheroes were Jewish. Superman, Batman, Captain America, Captain Marvel, Spider-Man, the Fantastic Four – all Jewish. Even Mighty Thor and the Asgardians were Jewish. Which is to say that most of their creators and publishers were Jewish, many of them immigrants’ children from the Lower East Side, Brooklyn and the Bronx. Like blackface minstrelsy, vaudeville and Tin Pan Alley, comic books represented a low rung on the cultural ladder, within reach of immigrants’ kids. In comic books they not only found employment, haphazard and ill-paid as it often was, but lived out their fantasies and created whole fantasy universes for millions of readers. In doing so they played significant roles in creating American pop culture. Following the custom of the times, few of them signed their Jewish-sounding names to their work. They became Bob Kane or Stan Lee.

Jacob Kurtzberg is a good example. Born in 1917, he grew up in a tiny tenement flat on Suffolk Street near Delancey Street, the older of two sons of immigrant garment workers. The constant fighting with other kids’ street gangs, Jewish boys against Irish, Italian and black, grew him up feisty and defensive. It also left him with the intimate understanding of hand-to-hand combat that would show up in his brawny drawings. “I hated the place,” he would tell Comics Journal’s Gary Groth in 1990. “I wanted to get out of there!”